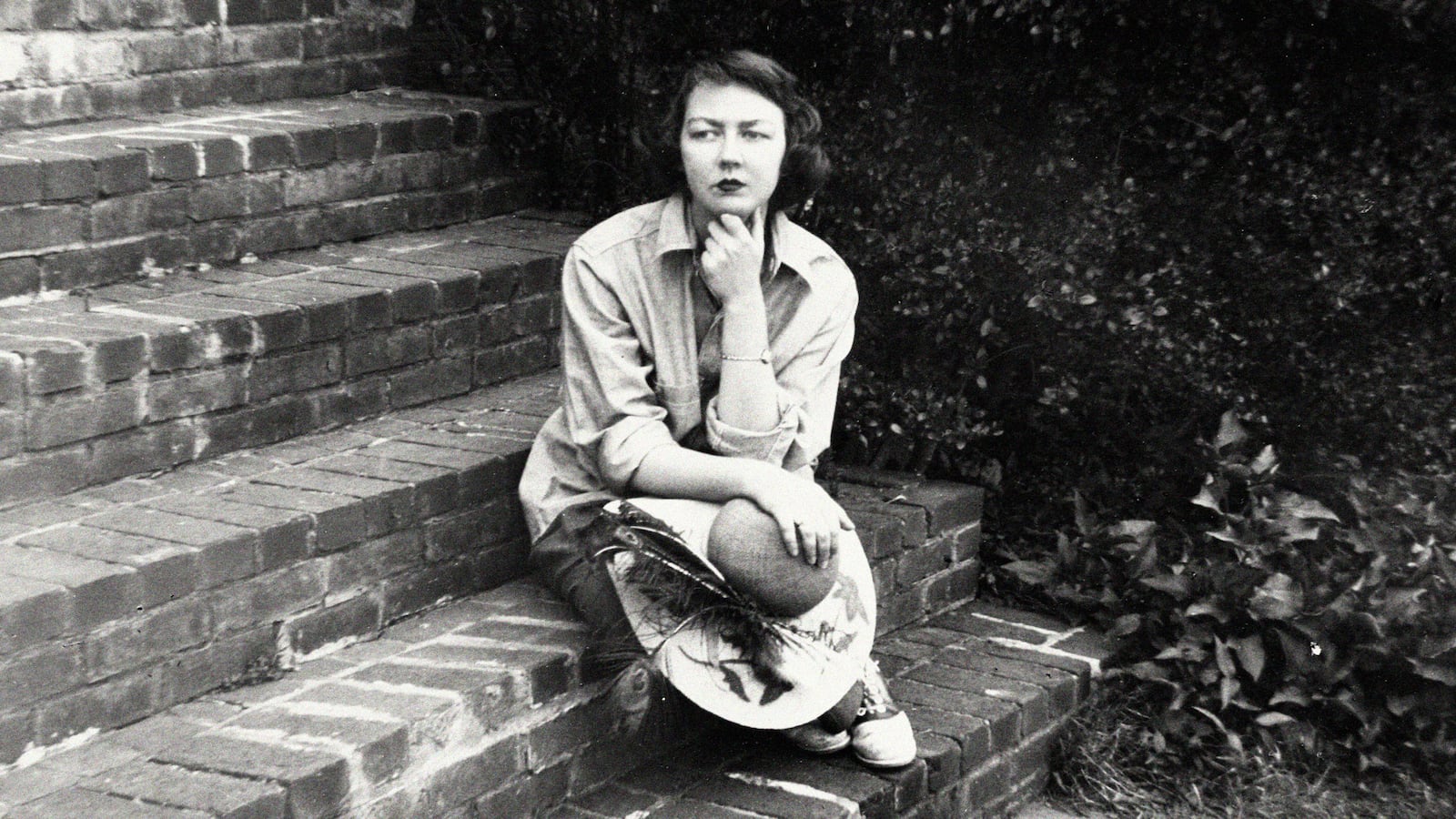

When celebrated American novelist and short story writer Flannery O'Connor died at the age of 39 in 1964, she left behind an unfinished third novel titled Why Do the Heathen Rage? Scholars who studied the material deemed it unpublishable. It stayed that way for 40 years.

Until now.

For more than a decade, award-winning author Jessica Hooten Wilson has explored the novel’s 378 pages of typed and handwritten material—transcribing pages, organizing them into scenes, and compiling everything to provide a glimpse into what O'Connor might have planned to publish.

In Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? Hooten Wilson introduces O'Connor's novel to the public for the first time and imagines themes and directions O'Connor's work might have taken. Including illustrations and an afterword from noted artist Steve Prince (One Fish Studio), the book unveils scenes that are both funny and thought-provoking, ultimately revealing that we have much to learn from what O'Connor left behind.

The following is excerpted and adapted from Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? by Jessica Hooten Wilson:

We are so good at knowing what is good and evil… in hindsight. It’s easy to denounce the Crusades or the Spanish Inquisition or colonization. Forget going back that far; we can stand high and proud above those cowards who permitted their Jewish friends and colleagues to be boarded onto trains and shipped off to execution. Surely, we would have done differently. We would have fought on the side of good in every previous battle in history and never have been blinded by a system of oppression and injustice. But the truth is not that simple. Flannery O’Connor asserted that one must “measure oneself against the Truth and not the other way around.” The proud stand above the truth, but the “first product of self-knowledge is humility,” O’Connor writes. She was humbled by confronting her own failings. As often as O’Connor held the mirror of judgment up to others—especially her readers—she placed that same standard before her own face.

What I learned while working on O’Connor’s unfinished novel, now being published more than sixty years after she worked on it, is that we are all “goods under construction,” as she once said. O’Connor was on her way, as we all are, toward knowing what is good and living into that reality. She failed. She treated some people wrongly during her lifetime. She missed the opportunity to know others because of her unjust biases. And yet, she was also a genius—an artist with profound insight into the human condition whose work often transcended the limits of her personal limitations. In O’Connor’s unfinished novel, readers are permitted to see how both things can be true at the same time: Someone can be a formidable author from whom we can learn while also being someone who was in the process herself of learning and growing. Reading Why Do the Heathen Rage? gives us the opportunity to practice charity.

In O’Connor’s novel, Fellowship Farm is a thinly veiled allusion to Koinonia Farm—koinōnia means “fellowship” in Greek—which was founded in Americus, Georgia, in 1942, only two hours from O’Connor’s home in Milledgeville. It began making headlines in 1956 after its founder Clarence Jordan sponsored two African American students who sought admission to the University of Georgia. In 1957 O’Connor’s friends Father McCown and Tom and Louise Gossett invited her to join them on a visit to the community. She declined, relating to her dear friend Betty Hester that the trip would be “inconvenient in more ways than one.” Yet she writes, “I wish somebody would write something sensible about Koinonia.” While O’Connor agrees that the community “should be allowed to live in peace,” she disagrees with the hagiographic write-ups about its mission. Although she had not yet been working on Why Do the Heathen Rage?, O’Connor shows that she attended to the news about Koinonia with mixed feelings of support and anxiety.

In 1957 Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, a group primarily located in New York, attempted to show her solidarity with the interracial farming community. She boarded a Greyhound bus and traveled down to Georgia during the final two weeks of Lent. On her third night at Koinonia, Day and her friend Elizabeth sat watch for the farm, which had been under attack since Jordan’s stance for integration had become more public.

The two women sat in a parked station wagon, listening to cicadas whirring and spinning in the air. An oak tree spread its arms so wide and high it cast centuries of leaves in a cover that hid the stars. Day and Elizabeth began to sing vespers to one another in low voices. Day was sixty, with a heavy chest, a small waist, and a determined chin. She often wore her hair pulled back beneath a handkerchief; her dress was homespun. Nothing could be heard but the sound of their low-sung hymns and the buzz of the insects overhead until a sudden spattering of sound: gunshots pop and crack through the stillness. Their car was peppered with gunfire by an unseen passerby. After the assailants shot at the women, they accelerated with full force and raced away. Neither woman was hurt. Neither ducked. Neither moved. They sat immobilized by fear. Within seconds, their song had been hushed by violence.

Thankfully, neither Day nor her friend was injured in the attack. O’Connor’s response to the news, which she read from Day’s column in the Catholic Worker, was, by her own lights, “ugly and uncharitable—such as: that’s a mighty long way to come to get shot at.” Yet O’Connor writes in the very next sentence, “I admire her very much.” She then muses, “I hope that to be of two minds about some things is not to be neutral.”

O’Connor expresses these two divergent perspectives in Why Do the Heathen Rage? In a few of the manuscripts, Oona’s group actually runs Fellowship Farm, which is located either in Osagoola, New York, or Rocky Branch, Tennessee. However, “Friendship, Inc.” becomes the group’s designation in the letters in which Oona describes her mission. Despite the similarity between Friendship, Inc., and Koinonia, from which O’Connor likely drew inspiration, O’Connor does not seem to be parodying the group. On the one hand, Walter is aggravated by Oona’s intrusion into Southern politics, but on the other hand, he agrees with her theoretically about the need for social justice. He defends the farm to his father as an example of Christian living.

Walter’s parents express the alternative point of view; both are outraged at the existence of Fellowship Farm or Friendship, Inc. They associate such groups with Bolshevism, which historically was an accusation that Jordan himself faced when he defended Koinonia. For O’Connor, Koinonia was a reality that confronted her assumptions about gospel living. As Charles Marsh explains it, Koinonia Farm embodied “that abrasive quality that the apostle Paul had described as the willingness to appear freakish and peculiar.” While O’Connor may have wanted to embrace the ideas that led to Koinonia’s founding, she seems to doubt in her letters whether she herself would be comfortable living in a similar fashion. This apparent divide between her cognitive assertions and actual practice, especially concerning Christianity and the civil liberties of African Americans, is evidenced in O’Connor’s fiction and letters from the last few years of her life.

In O’Connor’s restored bedroom there is only one piece of art set high on the bookcases: a portrait of Louise Hill, the African American woman who cared for the O’Connors’ home. It was painted by O’Connor’s friend Robert Hood and given to her as a gift. The portrait is impressionistic; many of the colors appear to melt into one another. If you stare at it for long, the face begins to look like an icon.

I picture Flannery in this museum-curated version of her bedroom, without the orange crate beneath her desk with its assortment of unorganized papers, her newspaper clippings scattered across her bed.

“Types faster than I can think,” she laments aloud, echoing her letters.

“What’s that?” a voice says from the other side of the armoire. Louise might be dusting the portrait of herself again this morning, feigning that the room needs cleaning.

“Louise, my mornings are nonnegotiable,” Flannery might snap. Her glasses pinch the bridge of her nose and her eyes dart back and forth over her near-empty page, trying to remember the thought she has lost. Every day that she could (even on Sundays in the final years of her illness), Flannery worked from 9 a.m. to noon, hoping for no interruptions.

According to Flannery, Louise often came in to dust her own portrait and admire her image. There was a gold crucifix on the wall behind Flannery that would have been figuratively boring into her neck. The hanging Christ on the cross demands that we be charitable, but sometimes all we can muster is suppressed wrath over wasted reflections.

Excerpted and adapted from Flannery O'Connor's Why Do the Heathen Rage? © 2024 by Jessica Hooten Wilson, published by Brazos Press and reprinted here with permission.