As an anxious nation awaits a grand jury decision in Ferguson, Missouri, the Florida law enforcement officials who handled another controversial interracial shooting have come forward to describe the lessons learned—and what goes on behind the scenes when a small town’s simmering racial tensions burst into the national media spotlight.

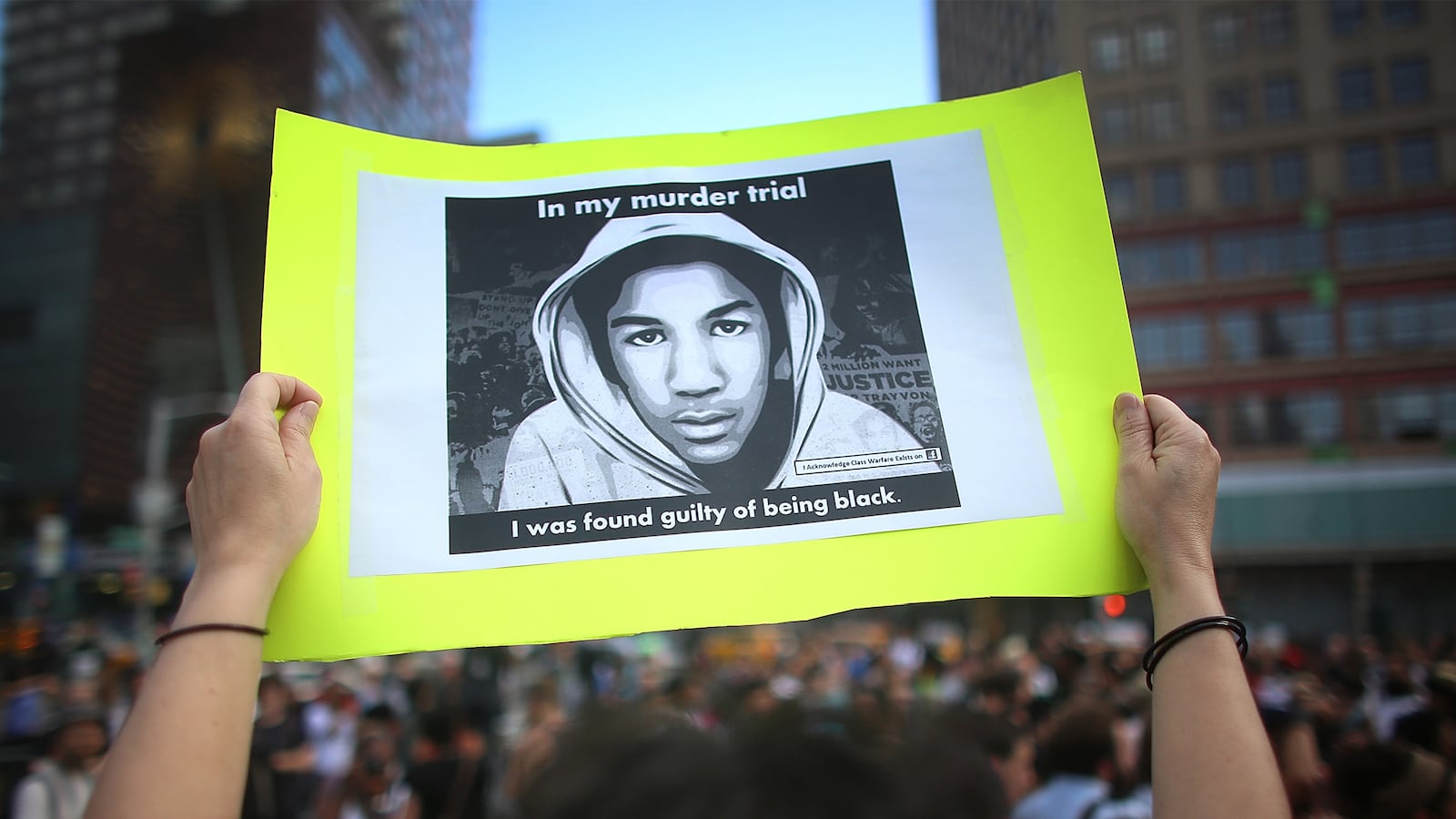

Last month at an annual police conference, Seminole County law enforcement officials described in unusually frank terms how the 2012 fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin sparked a social media-era version of Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities—complete with scheming activists, hired-gun protesters, panicked local politicians and prosecutors, and a voracious national media—that nearly torn the town apart.

“Local U.S. law enforcement agencies,” warned current Sanford police chief Cecil Smith, who is African-American, “are just one incident away from a major catastrophe.”

Racial tensions date back decades in Sanford, where in 1946 the police chief ordered black baseball icon Jackie Robinson off the field in the second inning because the town was supposed to be segregated. Death threats forced Robinson’s move to Daytona Beach, where he broke the minor league color barrier in March, instead of the planned city of Sanford, which would issue an apology to Robinson’s family in 1997.

Even before that, in 1911, a traditionally African-American community within Sanford known as Goldsboro—the second largest settlement of freed slaves and their descendants in Central Florida, where Robinson stayed when he first arrived in Sanford—was incorporated into greater Sanford against its residents’ collective will, and a $10,000 debt to the community that emerged from the municipal merger was never repaid.

“You would think that over 100 years ago, people would go beyond that point,” Smith said. “It hasn’t. It still resonates in the Goldsboro community.”

Flash forward to 2012, police officials said, and it’s clear in retrospect how the reaction to the Martin shooting unfolded as it did.

“If you put a kettle on the stove with water, after a while it boils,” said Smith, describing deep-rooted racial tensions in Sanford. “It boils and boils, a little steam, a little steam. But what happens when it runs out of water? It burns, it blows up, and in this essence that’s what took place,” Smith said.

In the chaotic weeks after the February 26, 2012 shooting, police officials said, the Seminole County state attorney left the already-fractured department swinging in the wind, allowing police to take all the blame for the growing controversy when in fact it was the state attorney’s office, according to Smith, who chose not to charge Zimmerman. He said the police had recommended a manslaughter charge.

Florida state attorneys (the equivalent of district attorneys) are legally barred from commenting on cases before charges have been brought, a spokeswoman for the Seminole County state attorney’s office noted. Seminole prosecutors only had the case about seven days before Governor Rick Scott appointed a special prosecutor to take over the case from Seminole state attorney Norm Wolfinger.

Within three weeks, the new special prosecutor charged Zimmerman with murder. He was acquitted in a jury trial last year of all charges.

About a week later, Wolfinger announced his retirement after 27 years in office. He could not immediately be reached for comment.

One Florida law enforcement who spoke on the condition of anonymity pointed out that police could have simply made an arrest themselves. “They don’t need permission from the state’s attorney to arrest on a felony, at any point that they believe they have probable cause.”

By the middle of June, as politicians and prosecutors battled behind the scenes, public pressure up front forced Sanford’s white police chief Bill Lee to step down— the first of five chiefs who would rotate through the post in two years.

Smith, the current police chief, called Lee a “scapegoat” who was “thrown to the wolves” to satisfy political critics. The black chief that replaced him—Darren Scott—said he had been a newly promoted captain for just two weeks when he was given ten minutes’ notice of his new post.

“This is exactly what [was] said,” Scott recalled. “I’ll never forget this: ‘In ten minutes we’re getting ready to announce that Chief Lee is stepping down, you are now [the new] police chief.’”

“I pretty much said ‘what the fuck just happened?’”

As the national media and thousands of protesters descended on Sanford—a sleepy, 54,000-resident, 26-square-mile town that swelled by 20,000 people in seven weeks—the bonfires began crackling to life.

“One of things that I learned personally was that there are groups out there who hire people to protest,” Smith said, apparently referring to national civil rights leaders without naming anyone specifically.

“They will get people to do nothing but walk around with signs [and] raise Cain in your community? That’s all they do. They get on the buses, they show up, they raise Cain, and then they get on buses and then they leave.”

Last April, a group of law student activists known as the Dream Defenders descended on the Sanford Police Department to protest the lack of a Zimmerman arrest, but not before apparent attempts to choreograph their incarceration.

“There were backroom meetings with the Dream Defenders saying, ‘We want to get arrested, how can we get arrested in front of the police department so that it looked great on television?’ Smith said.

“The decision was made that, ‘If you want to sit outside the police department and lock arms, knock yourself out.’ But we were not going to give them the money shot of them being arrested at the expense of the Sanford Police Department.”

(“That conversation never happened I don’t know what he’s talking about,” Dream Defenders Executive Director Phillip Agnew told me on Wednesday.)

Smith also described how thousands of voicemails and tens of thousands of emails completely shut down the communications in Sanford’s local government offices, repeatedly, throughout that spring.

Then came the Plague of the Skittles.

“Someone had tweeted essentially instructions to mail Skittles and Iced Tea [cans] to the police department—which came in in droves: hundreds and hundreds of boxes. We had to get outside storage units.”

By the start of Zimmerman’s murder trial last June, the media frenzy was in full bloom.

Just hours before the late-night verdict came down, Seminole County Sheriff’s Department Major Ed Allen and others tuned in to Headline News’ Nancy Grace to find Zimmerman neighbor and media gadfly Frank Taaffe, live on satellite from outside the courthouse, claiming he “knew” that the jury was split, and even providing the yea-nay count to Grace—who, in a rare reminder that she is, in fact, a lawyer— furiously challenged Taaffe and then drowned him out in a fusillade of shrieks, snorts and screaming.

“And our folks are standing guard outside the [jury room] door!” Allen says now, still incredulous a year later. Officials scrambled to react.

“We’re able to grab the clip, run it to the sheriff, then it goes to the judge, [who sends someone] out to media city, asks [Taaffe] to come in…the judge asks him” how he knows the jury counts.

“Of course he has no answer he is purely speculating,” Allen said.

“And then of course, there’s Zimmerman, who will not go away,” Allen said. “He just does all kinds of ridiculous things.”

He then went on to recount how a jailed-Zimmerman’s (now-ex) wife Shellie came to be arrested on perjury charges, after the couple devised a code to hide tens of thousands in online defense fund donations from the court.

“We’re monitoring every call in and out of the jail and we hear this ridiculously coded conversation between them and we understand exactly what is happening,” Allen said, shaking his head.

Almost miraculously and to the enduring credit of local cops on the ground, Sanford saw zero violence and no arrests in the aftermath of the jury verdict. Back in Ferguson, however, there is diminishing hope that the grand jury verdict on whether to charge a white police officer in Michael Brown's death will be greeted with non-violence. Since the shooting this summer, clashes have produced 155 arrests, as a largely white and heavily armed Ferguson police force has cracked down on protesters and journalists.