We whooshed up to the opening of Pop Life: Art in the Material World on the fourth floor of the Tate Modern, got out and were immediately confronted by Jeff Koons’ Rabbit, aka The Brancusi Bunny, alongside Andy Warhol in a fright wig. To its left was a video of the 2007 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City in which, floating above the crowd was, the Brancusi Bunny, now a 53-footer.

Click the Image Below to View Our Gallery

Well, Warhol and Lichtenstein-derived images have been recycled back into mass culture, via advertising, for years but this represented a clear advance. Rabbit had been originally cast from a blow-up toy and Koons, the messiah of art–as-self-realization, had contrived to have his version embedded in the popular consciousness by way of a famous parade in a famous city. Truly, this was the new Art Power in action.

ADVERTISEMENT

Pop Life, which runs through January 17, 2010, was originally to have been called Sold Out and it is another sign of Art Power that unhappy artists had it retitled. The idea was brought to the Tate by Jack Bankowsky of Artforum. Catherine Wood of the Tate says “the original proposal was much broader. It was on this theme but with more artists, bigger.”

The theme being? Well, moving on through, the agenda of Pop Life became clearer, if not simpler, because it’s not so simple. The Warholiana, and there’s lots of it around, does not include the classic Elvis and Liz humdingers, rather diamond-dusted portraits of Josef Beuys and such examples of the routinely trashed late works as the Mick Jagger portrait.

A Warhol Blackgama ad is included, as are a 1986 ad in which he is photographed sitting in front of a self-portrait. The caption reads: “I THOUGHT I WAS TOO SMALL FOR DREXEL BURNHAM.” Also the episode of the soap, The Love Boat, in which he appeared. This was Warhol’s zenith so far as getting through to the mass audience went.

The catalogue notes that this was produced by Douglas Kramer, but not that Kramer was a major art collector. Pop Life is kept aloft by an interweave of such connections between the art world and its financial support systems. It suddenly seems relevant that the show on the floor below Pop Life was showing the collection of UBS, the Swiss bank, that discontinued its art banking earlier this year, and which is now being pressured by the US to divulge details on a list of private clients. And, for that matter that the Drexel Burnham ad came out the year before the company was indicted for insider trading. This lead to their bankruptcy and the subsequent non-award of the 1990 Turner Prize in, um, the Tate. Pop Life sensitizes you to the survival systems of Art in the Material World.

Two Ashley Bickertons in the show offer pointers. On the surface of Tormented Self Portrait, a 1987-8 piece, he painted the logos of whatever products were a par of his life, including Renault, Fruit of the Loom, Marlboro Light, and his school Cal Arts. A ticker on the second work, Still Life ( The Artist’s Studio After Braque) was supposed to record the piece’s constantly rising price. It stood at $15,000,000, which seems optimistic during these tough times but being part of a hot exhibition won’t hurt.

So the show is about money and marketing but then as you move on you see that it is about much else too. You got a hint in Spiritual America, the Richard Prince appropriation of the Gary Gross 1975 photograph of ten-year old Brooke Shields, standing naked in her bath, glimmering where not made up. This had been framed, and hung in a square space, the size of a boudoir and painted a stifling dark-red. Voyeur heaven.

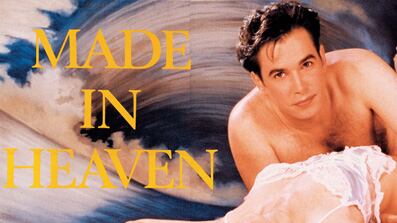

There was no whiff of the illicit in room 9, which has been dedicated to Jeff Koons’ Made in Heaven. Here the artist records athletic sex with his then wife, Ilona Staller, the Italian porn star known as La Cicciolina, in images silk-screened onto canvas and sculptures in plastic, glass and marble. The ardor is romantic and the dollops of semen, the erections, the anal penetration are detailed, as in one of his favorite pieces, Ilona’s Arsehole, in which the said body part looks like a demurely folded rosebud. As with the Art World-rejected Warhols, this is in line with Pop Life’s rehabilitative agenda because when Made in Heaven was shown at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York, in 1991 many grumped that the hotshot artist had gone way over the top.

Room 10 continues the sexual leitmotiv, being devoted to the work of Cosey Fanni Tutti, who engaged in person with Pornoworld, and used the experience to make a show, Prostitution, at the London ICA in 1976. Included here is a page from the Evening News recording police interest in the artist’s modus operandi, headlined YARD ACTS OVER THAT SEX SHOW. And room 15 contains just a 60-minute video featuring Andrea Fraser, who is best-known for art world-related Performances, as when she enacted the role of a docent, and gave museum tours.

For this 2003 piece, Fraser got her gallery to find a collector willing to pay $20,000 to sleep with her and to agree that this event be videotaped as an artwork. The handing over of the cash is not on the tape and the identity of the collector remains unknown.

The artists in Pop Life expected a backlash. They had been talking about it at a dinner before the opening. “We knew something was going to happen. A trap had been laid for the press,” Ashley Bickerton says. “We were taking bets as to whether it was going to be the Andrea Fraser or the Prince that caused the controversy.”

He had guessed wrong. When the police arrived it was to scrutinize and remove the Richard Prince. The catalogues also became a no-no. Temporarily, the Tate hopes.

“The hilarious thing about it is that the original pictures were taken in the 70s,” says Gavin Turk, whose work in the show includes Pop, his self-portrait as Sid Vicious. “And then it was reappropriated by Prince in the 1980s. And it’s been floating around the art world ever since then. It’s way over 25 years old. It’s very weird. But then, you know, this is London, isn’t it?”

So to room 13, which forefronts another tainted art event. Red, Black, Green, Red, White And Blue, Pruit Early’s 1992 show at the Leo Castelli Gallery. This show had a hip hop soundtrack and was built around such elements of black culture as images of Martin Luther King, The Jackson 5, and NWA. Attacks on the show as racist were scalding.

The work disappeared, apparently from the record, but here they are again, in a gold-painted room, just as it had been at Castelli, albeit a third of the size. “That’s the first time that that room and all the works have come back to life,” says Catherine Wood. “The show’s not remade as such. It’s just reinstalled. They look incredibly new those pieces, don’t they? They haven’t really been shown. After the scandal.”

Jack Early and Rob Pruitt were at the Tate opening. “We got death threats over that show,” Early says. “We went from signing autographs one day to the next day people crossing the street when they saw us coming, I promised myself I would never make art again. And I didn’t set foot in a gallery for 13 years, 12 years. I couldn’t even pick up an art magazine.”

Incidentally the Pruitt Early show looked good at the Castelli Gallery. It looks good at the Tate too and in this very different climate no element of racism can be discerned. It is equally to the point that when the Gary Gross photographs of Brooke Shields were originally published by Playboy Press in the 1970s, several questioned the common sense of Brooke’s uber-stage mother, Teri, but there was no public scandal. Pedophilia was a thing of the shadows then, not the ubiquitous klieg-lit horror story, as today.

The choice of work by two other mega-artists illuminate Pop Life. The curators have not replicated the Louis Vuitton store that was in Takashi Murakami’s Guggenheim retrospective—the working model of Keith Haring’s Pop Shop makes that point—but there are Murakamai goodies here which suggest his seamless blend of art and merchandising, including the sneakers he made for Vuitton and Issey Miyake, and some miniature figurines that were sold with packs of chewing gum from vending machines.

As for the Damien Hirsts, they were all from Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, the artist’s solo auction at Sotheby’s which was held at the tippy-top of the market, and just before the turning point of the boom. They include Aurothioglucose 2008, a spot painting on a gold background, and False Idol, the white calf with gilded hooves embalmed within a vitrine, which was picked up by the Fondazione Prada.

Jack Bankowsky in his catalogue essay describes the auction as “the artist’s masterwork.” An initial reaction to this diktat is a Warholian “Wow!” But then you realize that what Pop Life is approaching here in the inner meaning—or at least question—of the show, which is not the trite observations that some artists are getting even richer and more famous than footballers these days, but that some artists are using fame, riches and marketing as art materials. And the Thursday morning after the opening the inflatable Koons Rabbit was floated above Covent Garden like a blessing.

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Anthony Haden-Guest is the news editor of Charles Saatchi’s online magazine.