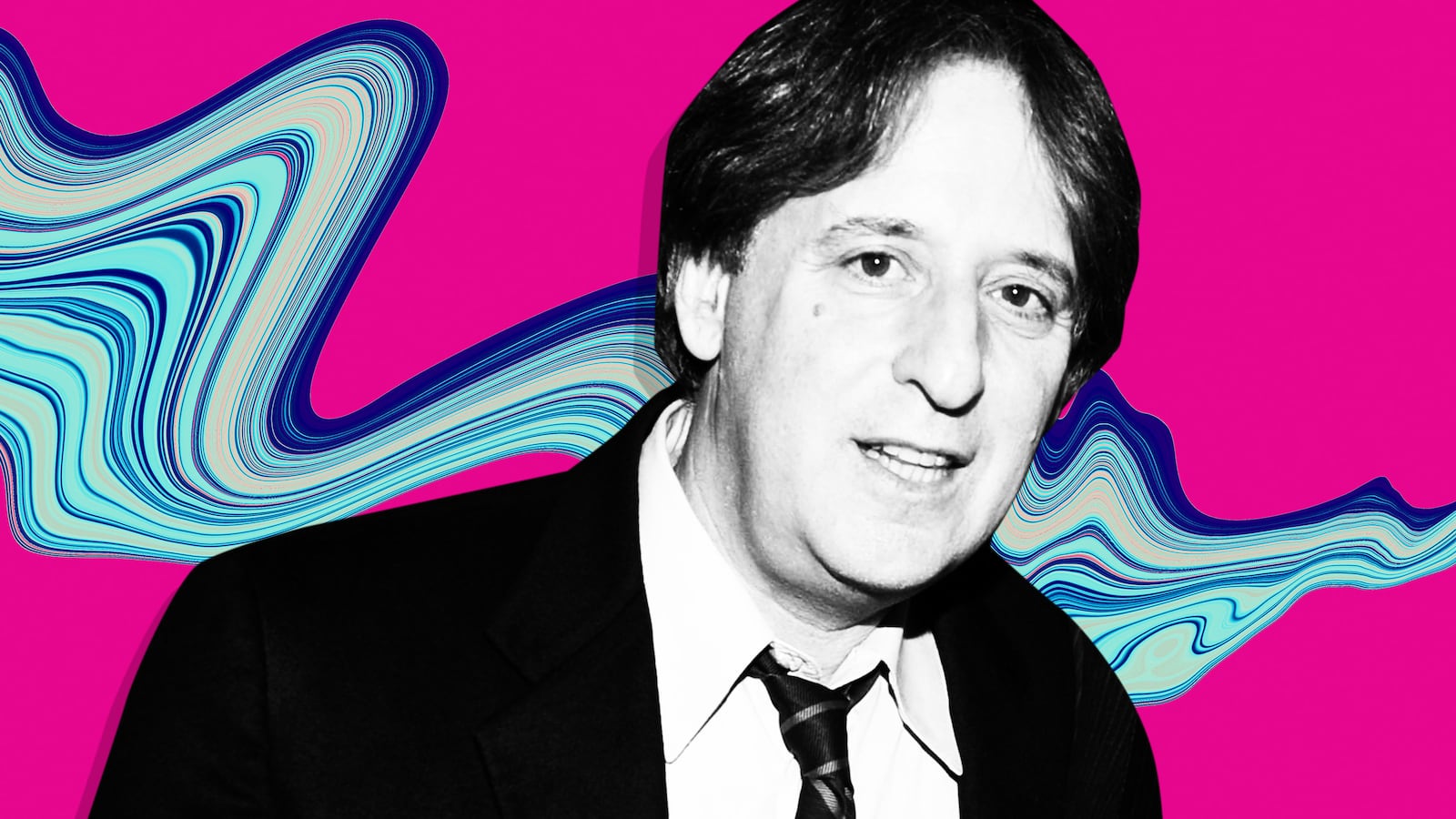

Few people outside the media biz have heard of Ira Rosen.

Those who pay attention to this sort of thing might remember him as the 60 Minutes senior producer who played a cameo role in the legendary CBS News program’s #MeToo moment, in which Rosen was himself accused of creepy sexualized behavior toward younger women (allegations he heatedly rejects) as he tried in late 2018 to save the reputation of his longtime boss, then-executive producer and former CBS News chairman Jeff Fager.

“In the pig culture that was CBS and 60 Minutes, Ira was a reasonably decent man,” a former CBS colleague told The Daily Beast—hardly a lionizing epitaph.

“He is somebody who works all the angles like crazy,” said another ex-coworker, recalling a meeting between Rosen and a top FBI official who, in Rosen’s view, was offering insufficient cooperation for a 60 Minutes story. “You’re selling me schmattas when you have Armani suits in the trunk of your car,” Rosen allegedly complained to the uncomprehending G-man, who apparently was unfamiliar with the Yiddish term for “rags.”

“He’s this nebbish-y and nerdy guy. He’s barely 5 feet tall,” this person added (shaving around 7 inches off Rosen’s true height), “but he walks around like he’s 6-foot-5 and a male model.”

ABC News icon Sam Donaldson—who knew Rosen when, between bookended stretches at CBS, the producer worked at ABC’s Primetime program—told The Daily Beast: “As far as I could tell, he knew what he was doing. He knew how magazine shows worked. I can’t say anything one way or the other about how I felt about Ira, other than that he was fine!”—perhaps the most generous encomium anyone offered for this story.

“Ira relishes being the bad guy,” said a third former CBS News veteran who, like all of Rosen’s erstwhile CBS coworkers—including a couple of former colleagues Rosen encouraged this writer to call—insisted on anonymity.

The 66-year-old Rosen—who left 60 Minutes after Fager was fired amid accusations of fostering a sexist frat-boy culture and groping female underlings (which he vehemently denied), to say nothing of the sexual-assault allegations against disgraced former CBS chairman Leslie Moonves—is reverting to bad-boy form while reviving the recent CBS scandals in his new book Ticking Clock: Behind the Scenes at 60 Minutes.

The book, in which Rosen predictably absolves himself of any wrongdoing, contains a bowdlerized version of the allegations against him in an internal CBS investigation leaked to The New York Times—namely that he “occasionally made inappropriate sexual comments to his female subordinates, such as asking them to twirl and encouraging them to use their sex appeal to secure information from sources.”

In his exculpatory narrative, Rosen omits the “twirling” and “inappropriate sexual comments” allegations and claims that anyone who accuses him of “encouraging them to use their sex appeal to secure information” is willfully misconstruing a 2012 lecture he gave on developing sources at an investigative journalism conference.

“I said that reporters should be charming, make themselves an interesting person, and show emotions so people will know you care about their plight or story,” he writes. “And as I told the men and women attending, flirting (not sex appeal) is a tool in a journalist toolbox to use, something I witnessed Mike Wallace and others use to great effectiveness.”

“There was one allegation—this twirling thing—and it was raised once, it was investigated, and I was cleared,” Rosen told The Daily Beast. “I had due process.”

In his book, Rosen also neglects to mention his role in phoning Washington Post Executive Editor Marty Baron—with whom he had collaborated in an award-winning joint Washington Post/60 Minutes investigation on the opioid epidemic—allegedly to persuade Baron to kill the paper’s reporting on Fager.

“I absolutely called Marty,” Rosen acknowledged. “I called Marty and I said ‘When we did the opioid epidemic story, we made sure we knew the validity of our sources. Check out the sourcing of this thing and look at the documents. Take a look at the statements that CBS issued.’ And that’s all I said—take a look.”

Baron, in a recent interview with The New Yorker, said: “It wasn’t just me, by the way; five editors were involved in that story, and one of them was a woman. And all of us concluded unanimously that it did not meet our standards for publication.”

Ultimately, The New Yorker published Ronan Farrow’s investigations that cost Moonves and Fager their jobs.

“In their search for harassers, the Post reporters became harassers themselves,” Rosen writes. “Ultimately, the editors at The Washington Post said, their story on Fager ‘did not meet our standards for publication,’ and when it ran, it didn’t include any harassment allegations against him.”

Without citing evidence, Rosen claims: “So the Post reporters leaked their rejected story to Ronan Farrow of The New Yorker, who printed allegations of harassment by Fager, including that he touched women inappropriately at office parties.”

One of the reporters, Irin Carmon—who with The Post’s Amy Brittain had exposed the sexual misconduct of 60 Minutes correspondent and CBS This Morning anchor Charlie Rose—told The Daily Beast: “It’s certainly false that we leaked anything to Ronan Farrow. What kind of reporters would want to give away a story that they had spent months reporting on themselves? We were trying to get that story published until the end. I never spoke to Ronan before his story came out.”

Part memoir of his four decades in broadcast journalism (including 15 years at ABC), part score-settling gossip-fest concerning famous network television personalities dead and alive, Rosen’s soon-to-be-published book is hugely entertaining, rife with bizarre adventures such as his unlikely liaison with corpulent late-stage Marlon Brando (who gave Rosen a stock tip—buy Apple!—that he unwisely ignored) and Rosen’s warm friendship with charismatic, possibly homicidal gangster John Gotti Jr.

A section on Rosen’s wining-and-dining of former National Enquirer editor Dylan Howard to woo him for a 60 Minutes interview recounts Howard’s alleged confession that the supermarket tabloid published lies during the 2016 presidential campaign about Donald Trump’s opponents Ted Cruz and Hillary Clinton. “We also did UFOs landing in America,” Howard allegedly told Rosen. “We are a tabloid publication.”

Rosen’s book continues: “Trump had invited Howard and National Enquirer publisher David Pecker for dinner on July 12, 2017. Howard told me that while touring the executive residence of the White House, when he was just outside the Lincoln Bedroom, the president said to him, ‘Editor man, I’m glad I’ve been good for business.’

“He then asked if the former Playboy model Karen McDougal still loved him. ‘Of course she does,’ Howard said. Trump seemed pleased. Trump then told Howard the secret nickname he had for her, ‘the Hoover Dam,’ Trump said, ‘because she was always so wet.’” (Howard didn’t respond to a text message seeking comment.)

Not surprisingly, especially after the New York Post recently exposed many of the nasty bits, Ticking Clock is provoking indignation, along with plenty of eye-rolling, among Rosen’s former colleagues at both television networks.

“That wasn’t the intent of the book, and it’s not a dirty-laundry kind of book,” Rosen told The Daily Beast, arguing that his only purpose in writing it was to explain the role of TV news producers behind the camera as opposed to the rich and famous celebrities like the late Mike Wallace, who loomed large in Rosen’s life as both mentor and tormentor.

“Fuck you,” Wallace allegedly told him, hanging up after Rosen called to inform him that Wallace’s 1988 profile of cantankerous hydrogen bomb architect Edward Teller had just won a national Emmy award. The story had prompted a bitter fight between producer and correspondent, with 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt choosing Rosen’s edit, which, against Wallace’s wishes, featured Teller’s angry attempt to walk out of the interview, thwarted when the famous physicist couldn’t figure out how to disconnect his microphone. Rosen had gone to Hewitt over Wallace’s head.

“In fact, television is a producer-driven business,” Rosen said. “Though we were making one-hundred twentieth in some cases of what the correspondents were making, we were doing 20 times the work. We were finding the stories. We were booking the characters. We were writing scripts. We were putting the shows together. Only when The Insider came out”—the 1999 docudrama in which Al Pacino portrayed 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman—“did people actually see what a producer does. For the most part, we’re the forgotten person.”

Of course, an anecdote about an unpleasant dinner with Mike and Chris Wallace—in which the father relentlessly needled the son about his religious conversion from Judaism to Catholicism—seemingly has more to do with being an ardent gossipmonger than an award-winning TV producer. (Chris Wallace didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Without naming names, Rosen also includes a passage claiming that during the early 1980s, a 60 Minutes producer joined with a video editor to make a substantial amount of money by shorting the stock of a publicly traded company that was about to come to grief on the popular Sunday night show. When the late Don Hewitt learned of the potential insider-trading felony, he punished his staffers with only a two-week suspension, Rosen writes.

“I don’t want to get into it,” Rosen parried when asked for specifics.

Indeed, ABC Nightline co-anchor Byron Pitts, who’d worked closely with Rosen at CBS, was prominently advertised as appearing with the author at a 92nd Street Y event on Tuesday, the release-date of the book.

But after reading an advance copy—and being appalled by Rosen’s unvarnished portrait of his ABC News colleague Diane Sawyer and an anecdote involving the late Ed Bradley and oral sex, among other pieces of dirty laundry—Pitts withdrew, according to sources, and will be replaced by former Good Morning America news reader Antonio Mora. Pitts declined to comment.

Regarding Sawyer, Rosen claims that after exchanging pleasantries with Barbara Walters, her perennial in-house ABC competitor, she confided to him: “I hate that woman. Don’t believe a word she says. She knifes me any chance she gets”—an extremely un-Diane-like loss of self-control.

“Diane’s face was angry,” Rosen writes. “No smile. She had the look of someone who wanted vengeance.”

Asked for comment, ABC News and spokespeople for Walters and Sawyer resisted responding to Rosen’s assertions.

Among the other TV news celebrities who also get the Rosen treatment are former CBS Evening News anchor Katie Couric (“lazy and disengaged,” he claims, having worked on a single story with her) and 60 Minutes star Steve Kroft (“a deadly mix of narcissism and self-destruction”), both of whom—like Sawyer and Walters—declined to respond.

However, Couric’s longtime friend, Rockefeller Foundation executive Eileen O’Connor, a former broadcast journalist and Obama State Department official, told The Daily Beast: “Are you kidding me? I’ve known Katie for over 40 years”—since the late 1970s when both worked as desk assistants at the ABC News Washington bureau—“and she is the most non-lazy person. She’s one of the hardest-working people I’ve ever met in my life. Consider the source.”

With an apparent lack of self-awareness (as when he boasts in the book that airport security officers and airline pilots bowed before his status as a supremely well-connected and powerful producer for an important television show), Rosen seemingly identifies the source of his rancor: “Shortly after she arrived at CBS, I asked Couric if she would record a few lines for a video I was producing for my daughter’s bat mitzvah. I was told very directly by her assistant that Katie doesn’t do that and wouldn’t.”

Rosen, who spent five apparently disagreeable years as Kroft’s top producer, devotes many pages to the correspondent’s personal peccadilloes, including an entire chapter titled simply “Steve Kroft.”

“I’d rather work with a talented asshole than a nice person without talent,” Rosen writes—clearly placing Kroft in the “talented asshole” category.

“Steve Kroft told me when I first joined the show that Ira was a great producer except he can’t write and he makes shit up,” said a former associate producer, reflecting Kroft’s take on Rosen.

Say what you will, however; Ira Rosen can certainly write.