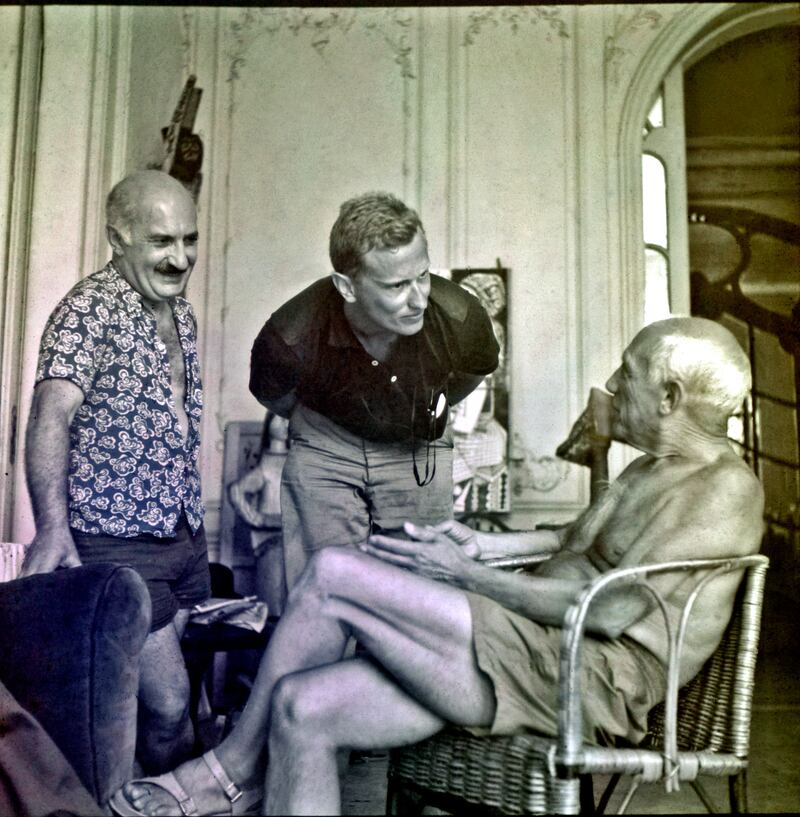

During Fred Baldwin’s last year in college in 1955 he took a leap of a faith and delivered a letter to Pablo Picasso of his own drawings in hopes to trigger his sense of humor.

At this point Baldwin had no pre-existing knowledge in art training and photography. However, Picasso found his drawings humorous and allowed Baldwin to enter freely in his studio and in his Villa La Californie. This defining moment changed Baldwin’s life forever. Any barrier generated by fear had been crushed and a new skill had been discovered.

Shortly after he finished college, Baldwin commenced a new career as a photojournalist. He was persistent and used his wit and charm to acquire friends in positions of power who would assist him with gaining access to locations where few or no photographers had gone before.

Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom provides a versatile archive including hundreds of astonishing black-and-white and color photographs capturing integral moments of his career. From capturing a day and a night with the Ku Klux Klan, southern poverty, coverage of a star-studded Nobel Prize ceremony, cod fishing in the Arctic Norway, polar bear expeditions near the North Pole, and much more.

Baldwin worked for an array of publications throughout his freelance career. His work was published in TIME, National Geographic, The New York Times, Smithsonian, Esquire, Natural History and many more. In 1983, Baldwin co-founded Fotofest, one of the most imperative and substantial photography festivals in the world.

Fred Baldwin sits down with The Daily Beast and shares some of his most exhilarating moments throughout his extensive career.

All photographs are from Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom by Fred Baldwin and is published by Schilt Publishing.

For more information: click here

Fred Baldwin (center) with Pablo Picasso, at the painter’s home in Cannes, July 1955.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingDid you ever explore photography prior to your meeting with Picasso? Was there a specific moment during this experience when you met with Picasso that ignited your passion for photography?

I bought my first camera, an Argus C-3, prior to going to Korea in 1950. I took nine rolls of film when I was serving as a Marine combat rifleman, but I didn’t continue the process seriously after I returned to civilian life. My photographs of Picasso taken five years later were made with a friend’s Rolleiflex. The Anscochrome color film in combination with the camera were sufficiently forgiving to allow me to get pictures on July 28, 1955, which was a miracle as I had no light meter and had never used the camera. The pictures proved that I was there but my passion was ignited, not by this miracle but by the combination of events that I call the Picasso Mantra: I had a dream—to meet Picasso; I used my imagination—to write him an illustrated letter with my own drawings; I overcame my fear—I was scared to death of making a fool of myself, but more important than anything else – I acted. Over four days I changed from being a college student terrified about finding a job and figuring out how to survive in the real world to a person who could do anything they wanted to do. I decided after graduating from Columbia in 1956 to become a photographer.

Lofoten Islands, Norway, March 1959. Curious cod fish in a net swim up to Baldwin’s underwater camera.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingPrior to your experience photographing cod fish in 1959, did you ever photograph wild life?

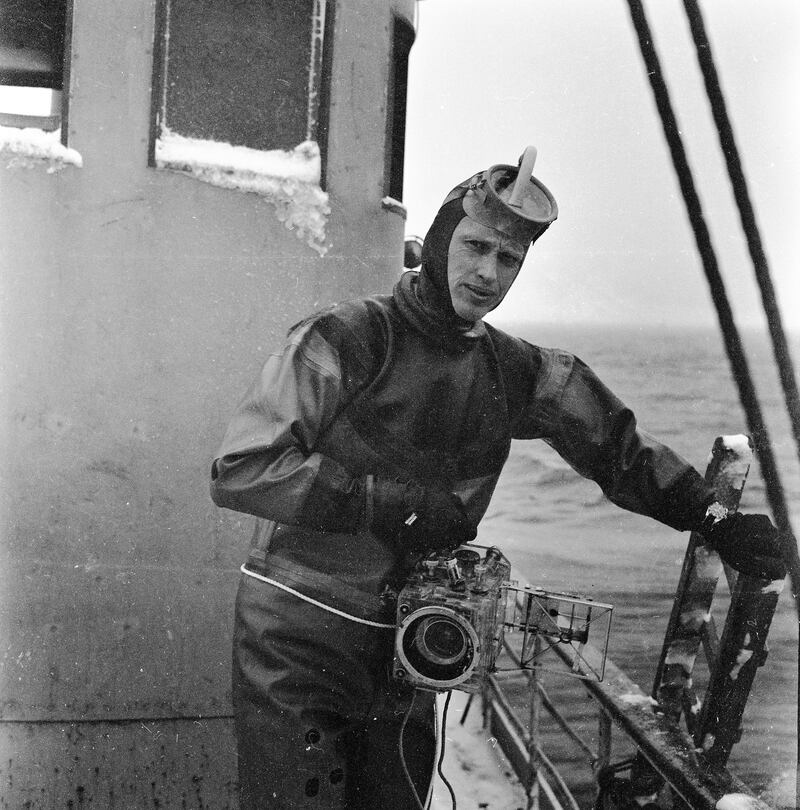

The answer is no. When I arrived in the remote Arctic islands of Lofoten in January 1959, I did what was now routine behavior for me: I checked in with the local officials, police and newspaper. It turned out that one of the reporters at the Lofotposten, Kare Skevik, who had been a radio operator in the Norwegian underground during World War II, loved to tease young foreigners like me. When I asked Skevik about the well-known annual cod fishing season in the Lofotens he said as a joke: “You should do something different. Photograph the fish from their point of view.” I asked him if the water was clear. He said: “Yes, and very cold.” With help from the Norwegian Navy, among others, what started as a joke ended in a series of images of cod fish that I photographed in nets underwater. They were later purchased by National Geographic.

Lofoten Islands, Norway, March 1959 – Baldwin holding an underwater camera in preparation for a dive in freezing waters to photograph cod fish.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingWhat was running through your mind when you worked with the Norwegian Navy with no prior knowledge on how to use Scuba equipment? How long did the process take?

The learning consisted of doing what I was told to do. For deep dives down to 50 meters I had a rope that was tied around my waist and after 13 minutes there were three jerks on the line and I would start up to the surface in order not to have to go into a decompression cycle. Apart from that the suits were warm in the almost freezing water and I dove alone most of the time but a frogman would always be suited up and ready to come in for an assist. But luckily this was never necessary.

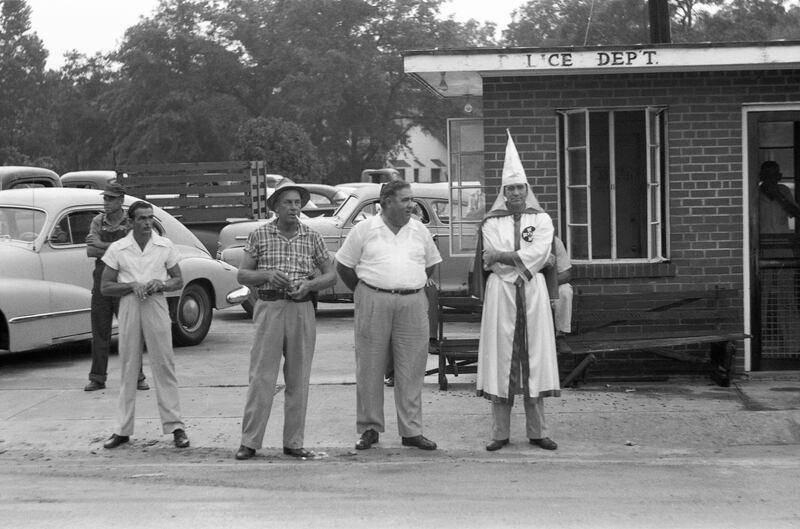

Ku Klux Klan, Reidsville, Georgia, 1957 – A Klan member, the Chief of Police and the Sheriff wait for the decorated KKK cars on their way to a ceremony to pass by.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingYou mentioned capturing the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia in 1957 was an accident while preparing for your first documentary project. Was that the first time you experienced photographing the racial divide in the South?

This accidental contact with the KKK in 1957 was my first attempt to break out of being a children’s photographer. On my way to photograph a tobacco auction in rural Georgia, inspired by the work of Farm Security Administration photographers like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, I accidentally stumbled upon the Klan. Prior to this encounter in 1957, I had passed by a KKK cross burning one night near Savannah in the late 1940s but I had no camera with me and I’m not sure I would have had the nerve to stop if I had a way of recording it. In 1957, years later with a camera in tow, I stopped. Perhaps it was the Picasso Mantra that led to this decision.

During the Civil Rights Movement you mentioned setting up a free photography service while photographing both white and black churches. Can you describe what that service entailed and how it was received in both communities?

In 1963 and 1964, I made my photography available to the CCCV (Chatham County Crusade for Voters) that was associated with Dr. King’s organization. I worked with Hosea Williams, who led the organization in Savannah. Hosea would contact me whenever he needed photographic coverage for the CCCV newspaper. This provided me with an inside look into what was going on in the Civil Rights Movement in Savannah. It wasn’t the fire hose and police dog coverage that photographer Charles Moore was getting in Selma, but it was what was happening in the First African Baptist Church where Mrs. Coretta King came to speak. I photographed mundane events that ultimately became significant such as voter registration efforts. The only time I photographed in a white church was to cover an integrated service at Christ Episcopal Church in downtown Savannah as a tribute to Dr. King after his assassination.

Civil Rights Movement, Savannah, Georgia, June 1964. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaks at the Civic Auditorium.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingWhat was your experience working with Martin Luther King Jr. as a freelance photographer capturing the inner workings of the Civil Rights Movement?

Working with the CCCV was a vitally important experience for me. This was the first time that my photography was not connected to an ego enhancing experience. For many years I had observed the consequences of exploitation. I saw it first hand when I worked at the family factory alongside poor whites and blacks. The photography that I practiced in Europe and Mexico dealt with dramatic tale telling and was based on a need to attract as much attention as possible. Now it was different. I came to understand that in order to fit into the middle of this new situation, I had to give up my God-given self-importance – especially my God-given white self-importance.

Peace Corps, India, 1966, Haystacks. “My attempt to photograph the Peace Corps program in India was fraught with frustration as I found India a compression of opposites both hideous and beautiful. The twelve hundred volunteers working there in 1966 sought to make progress among half-a-billion people. They were needles in the haystack, so I decided to spend several months photographing the haystack instead of the needles.”

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingWhat was one of your biggest challenges early on in your career and how did you overcome it?

When I decided to become a photographer after graduating from Columbia I had to start from scratch. Apart from investing in equipment, Leicas and a professional enlarger, I went to every museum and gallery that showed photography in New York and looked at every photography book I could get my hands on. I signed up for a workshop with Lisette Model but only lasted one session as I couldn’t consume the intellectual scrambled eggs that this tough brilliant artist provided me. I just needed a “camera club” approach to help me make sharp pictures. It was a shame because it turns out that Diane Arbus was in the same class.

The other challenge was to support myself. Moving in with my mother in Savannah only solved part of my survival problem. I borrowed the FSA idea of making long lists when I photographed the children of family friends. I asked the children from my list what they wanted to do for a day – fly a kite, go fishing, build a tree house and so on. I would shoot ten rolls of film, develop them in the bathroom and print the ones that survived my ignorance. Over six months my day rate rose from $40 a day to $400, a small fortune in those days but I didn’t want to be paid out of Mom’s cookie jar forever so this led me to the tobacco auction and my encounter with the KKK.

Ku Klux Klan, Reidsville, Georgia, 1957 – A car being decorated for a Knights of the KKK meeting.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingMy lack of confidence was also a huge barrier. Just after I finished the KKK shoot, I went to New York and visited Magnum Photos and the great photographer and curator of photography at MOMA, Edward Steichen. I showed them my children’s work. Magnum was not impressed but Steichen bought one for MOMA. But I made a huge mistake. I didn’t show my KKK work because I didn’t think it was any good. If I had shown these to Magnum they would have said, “You connected with the KKK. Go spend six months with them and nail this story.”

What do you try to achieve with every photograph you take?

Photos that Wendy Watriss and I took in Texas between 1971 to the mid 1980’s captured an intimate look into the everyday lives of people in four regions of the state. People allowed us into their lives and our work was enriched by their welcoming behavior. This work is being used to make a film called The Low Turn Row. In the film, the description of contemporary black family life is used to ground the cruel historic reality of racial discrimination and the failures of the Reconstruction and black voter registration since the 1900’s. The film is a history lesson about the long-embedded power of racism, class and discrimination.

The images that I took while following the Sami reindeer herders had another purpose. The extraordinary effect of the Lapland nature; both its breathtaking beauty and grim dangers of avalanches and whiteouts were the inspiration. They set up an agenda that put the reindeer in charge of the direction of their awe-inspiring story. I was following the reindeer because nature was in charge in Arctic Lapland.

Reindeer Migration Post Easter 1960, Kautekeino, Norway. An enlightening “Coffee Cook” with herders, Anders and Nils-Peter Sarah. “I met Anders and Nils-Peder Sara in Kautekeino, Norway which means in Samisk “between the reindeer grounds of the winter and the summer pasture by the sea.” An arduous education in ‘cultural communication’ was made possible by the frequent ‘coffee cooks’ where I learned from my hosts the Samisk survival lifestyle on many levels.”

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingIt takes a huge and sustained effort to make good photographs. I try to answer the question: “What do you try to achieve with every photograph you take?” The answer is: try to find new ways to create a surprise and raise questions.

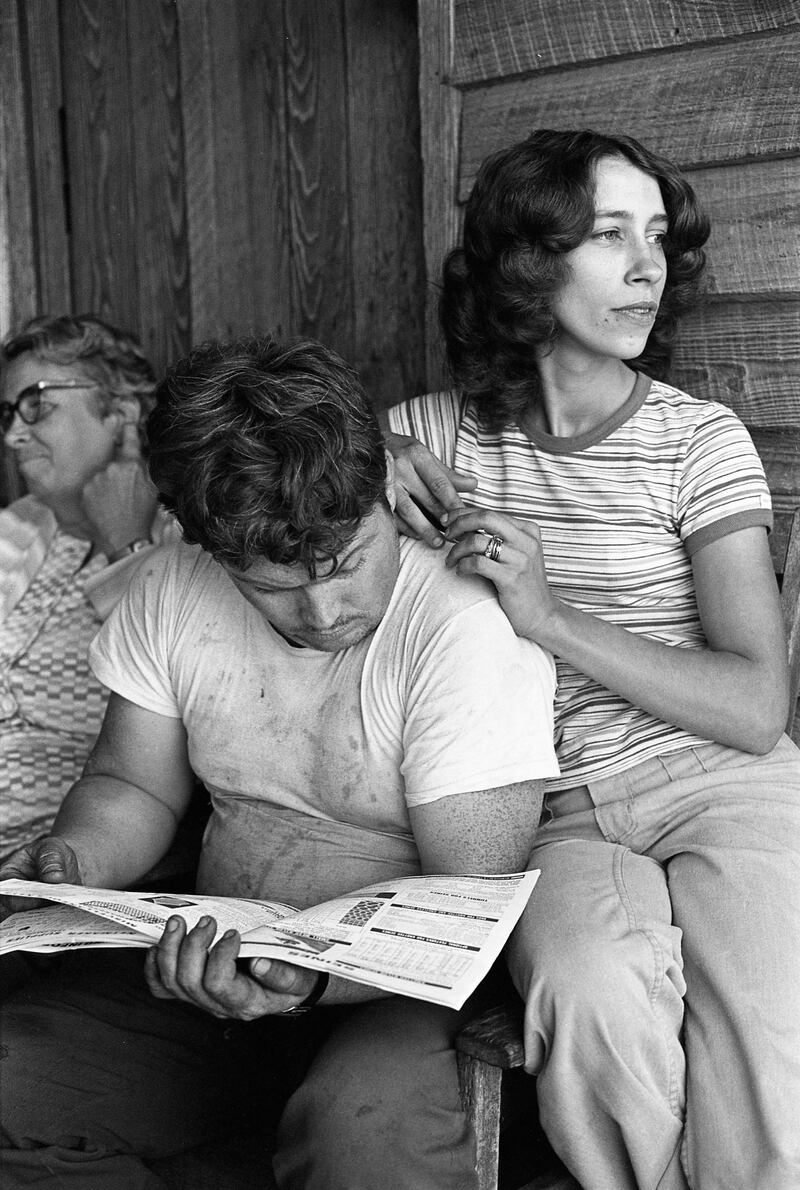

Southern Poverty, Savannah, Ga., 1967. A tiny, isolated, poor community located not far away from Savannah’s wealthiest parts. It was reported that families here suffered from five generations of inbreeding.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingYou and your wife Wendy Watriss had a collaborative photography partnership. Can you describe your working relationship on the Texas project? What was your biggest take away from this project?

When Wendy and I met in June 1970 there was an instant connection. She had just returned from West Africa where she was on assignment. Wendy’s approach was different from mine. She was not a storyteller who told stories about herself, but rather a natural born journalist who never stopped asking probing and intelligent questions with charm and conviction. She is also a voracious reader, and her ideas come from many points of view.

It’s necessary to understand that both Wendy and I had both, by choice and circumstance, spent much of our private and professional lives away from the United States. In my case, I was able to find more in myself away from the comforts of my own culture. Wendy’s work in Africa and Eastern and Western Europe did this for her. Our separate but mutual experiences formed a bond that enriched our relationship and shaped our collaboration.

We talked about ‘re-discovering’ our own country and decided to start in Texas, which Wendy considered more exotic than Bulgaria. We lived in a 13-foot trailer pulled by my old Mercedes Cabriolet and we did everything together, including photography and interviewing. When we parked on the back pasture of an African American farmer, things got more intimate as we had to create our own toilet with a USMC entrenching tool in a field. Texas became a ten-year project, off and on: We worked on the old southern, corn and cotton frontier; the German Hill Country; and the Mexican American border, from east to west - four different cultural frontiers of Texas.

Grimes County, Texas, 1972. For three years Baldwin and his partner Wendy Watriss lived in this 13-foot trailer parked on the back pasture parked on the back pasture of the African American family of Willie Buckhannon. “This was the base from which we photographed, collected oral history, and collected local history of the county.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt Publishing

Southern Poverty, Georgia, 1982. Baldwin returns to the poor community he first photographed in 1967 where families are reported to suffer from five generations of inbreeding.

All photographs are copyright Fred Baldwin from the book Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom published by Schilt PublishingWhat was your biggest take away from this project?

The fragility of democracy and the unending struggle to maintain it.

What inspired you both to create FotoFest in 1983 alongside European gallery director, Petra Benteler?

In 1982 Wendy and I went to Les Rencontre d’Arles de la photo in the south of France. There we found droves of photographers in the Hotel D’Arlatan, gathered around Jean Claude Lemagny, Director of the Bibliothéque Nationale in Paris. When we later learned about Le Mois de la Photo (Month of Photography) in Paris, where photography exhibits had been held in the city’s museums every two years since 1980, Wendy and I decided to combine the idea of Arles with the Mois de la Photo, with international exhibitions and portfolio reviews alongside a broad range of related programs. The first FotoFest was launched in March 1986, an internationally-oriented non-profit that was about bringing creative people together, here and all over the world. It’s also about important civic issues and social justice. It’s about men and women from many countries bringing their personal experience to give us a better understanding of what is happening in a larger world. Petra Benteler, who had been involved with the original idea, returned to Germany after the first FotoFest due to a family illness.

You’ve mentioned various times throughout your career that you still believe there is much work to be done in photography. What do you hope can be accomplished in the future of FotoFest?

Over the last thirty-three years FotoFest has interacted with photographers in North and South America; Asia from Japan to Singapore; East, West and Central Europe; Arab Countries; India – from over sixty-five countries and we need to continue our exploration through exhibitions, exchanges, and on-site visits. The world is filled with talented photographers and we have been asked to extend further regions, such as Africa and India, as FotoFest has recently done. In 2000, FotoFest formed a loose confederation of twenty international and U.S, festivals. We meet annually in Paris but we need to do more with this organization to encourage collaborative projects. Looking to the future, we instigated a transition in the last few years and now FotoFest has an executive director, Steven Evans.

Do you have any advice for young photographers interested in photojournalism?

Working as a photojournalist was never easy but it is far more difficult today. It is always necessary to have an aggressive approach, learn to work in unfamiliar environments and learn foreign languages. Magazines and newspapers provide a fraction of the time and resources that were once available. However, there are institutions that can help the survival process and a young photographer needs to find out about NGO’s and institutions that can help reduce the pain. It is also necessary to broaden your skills to include video, film and sound recording and work with platforms like Photoshop. It also doesn’t hurt to learn how to write.

Training in photojournalism is only the beginning of the process. A young photographer needs to understand the history of a chosen geographic target. There are organizations who you can work with to broaden your horizons: Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam, and the United Nations are good examples. Photojournalism oriented organizations such as Noor and Panos are also important. Online social documentary platforms like Magnum Residencies for Photojournalists and World Press Photo Classes are worth looking into. The most important attribute is the same as it always has been: an unswerving dedication to pushing as hard as you can in your chosen direction.

Fred Baldwin will be doing an Artist Talk and Book Signing Wednesday, December 4th from 6-9pm at the Aperture Foundation: 547 West 27th Street, 4th floor New York, NY 10001.

This event is open to the general public.