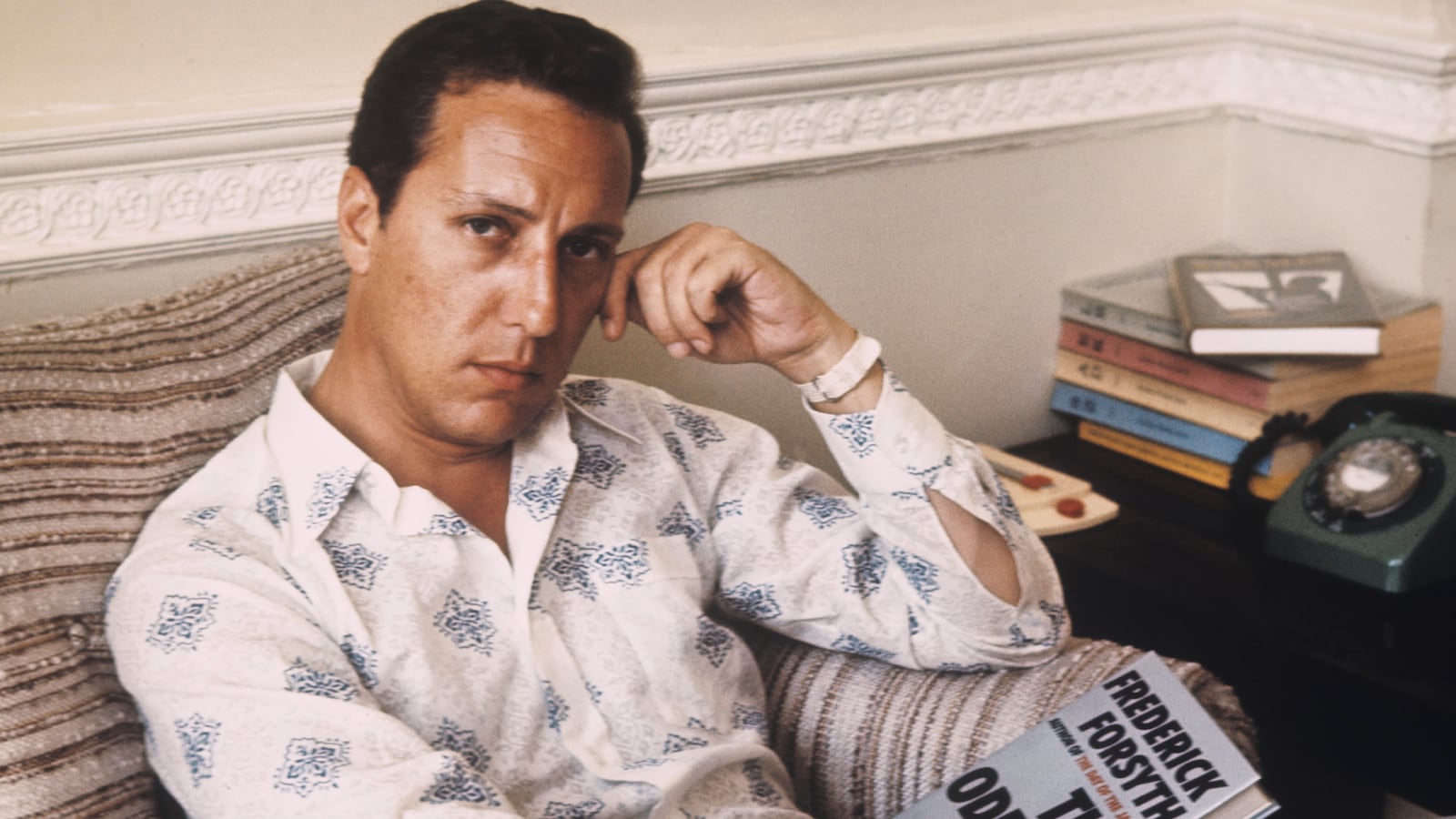

I grew up on thrillers—Ludlum, Follet, le Carré, and of course, Frederick Forsyth.

My father worked on a computer all day, so his literary escape was books on tape, and there was no better genre to keep a car full of five kids quiet and give his tired eyes a break than with spy thrillers.

After reading his memoir The Outsider: My Life in Intrigue and interviewing him, it is startlingly obvious why Frederick Forsyth was one of our first choices—the man lived what he wrote.

Forsyth made news recently for his admission that he was an MI6 agent, but that shiny object obscured a life full of mystery, adventure, and risk. Whether at a young age, when he was forced to slash an Algerian man trying to rape him, to his career as a journalist which took him to war zones, or when he found himself in bed (in the Biblical sense) with the secret police.

Why did you decide to write this book now, and how did you decide what to include?

I sort of fended off for years the idea that I should do an autobiography. I said no, I don’t really want to do that. That was still my view because I regard autobiography as having to be exactly pin accurate. You have to research it and get it absolutely right, because it’s a document of record. Whereas a memoir, as its name implies, is merely what you remember. It is more informal, you can make it jokey, quite humorous if you want. The reason I got up to it is really that friends of mine, we might be sitting around the table after dinner telling stories, and somebody would say, “Well Freddie, you should write that down!” So I thought eventually, “Why not?” So I did write them as anecdotes, one after the other, no particular linkage, no plot that proceeds from chapter to chapter. So that’s the way it’s been written, they are not really chapters, they are anecdotes. I’m saying to the reader, more or less, “Hey why don’t we just chew the fat, shoot the breeze, after dinner?”

Obviously the biggest news out of the book was the reveal about you and MI6.

No, it’s been far more than I thought it would ever be. And I may have upset some people in the business by being too overt. But I took the view, because I mulled it over whether to mention these episodes and I thought, well, there are departmental chiefs who have written their memoirs, and it’s not going to give away anything that is germane to the present day. We’re talking about stuff from way back in the Cold War. There’s no East Germany now. There’s no Stasis left. So I thought I wouldn’t even be giving away any tradecraft that would be of any use to anyone now. It’s memory lane. So I don’t know if people inside that community will accept that, they may or they may not. I was surprised at the amount of media attention because it was really a very small contribution. Just running a few errands really.

You had a very eventful life. What drove you to pursue relentlessly so many diverse and varied adventures? Not all of which were exactly safe.

I know there are danger freaks, and I am emphatically not one. But I think even as a boy I had an unusually large bump of curiosity. If I see a lid, I have to lift it. If I see a closed box, I want to open it and find out what’s inside. This is good if you want to be a journalist, because that is what we’re supposed to do—to find out. Some would say no, journalism is just reporting what goes on in a courtroom, what goes on in Congress, or what goes on on a football field. But there is an element inside journalism called investigative, and that is where a good journalist will find out about a scandal in high places, and it is part of a democratic society. So I had this curiosity to find out what was going on. The only way to do that was go there. So I ended up in places where I got into a scrape, and then with good luck got back out again. There were a couple places I got into where it was stupid to go. But there we are, looking back it was fun. It could have been scary, but now it is amusing. So I wrote it that way in the memoir and hopefully there is more funny in the book, than serious. But there is serious, and that’s the dying children of Biafra, which isn’t funny and you can’t joke about.

For some writers, humor is quite difficult to do well in writing. Do you feel similarly?

I don’t think I went out of my way to be funny. It was merely that some of the things that happened were crazy and even funny. Looking back, things that didn’t seem funny then now seem funny. The Czech Secret Police girl. I mean I just made love to a girl and asked her, “Where are the secret police?” And she responds, “That’s me.” Having to get out of East Berlin for another indiscretion, this time with the Defense Minister’s mistress. At the time I thought, “Whoopsie daisy! Not a wise move to sleep with this woman.” But it was too late by then. So recalling things like that, I’m not making them funny. I just think that now that I got into these scrapes and out of them they are.

One thing I couldn’t help feeling was, and I don’t know if luck is the politically correct word, but that you grew up at a time when large swathes of the world were “exciting” places to visit.

I mean the south of Spain when I was there in the mid-50's was Malaga, which was a very quiet, what’s the word I would call it, a traditional town. And there were three fishing villages between there and Gibraltar. Well the Costa del Sol is now just one long ribbon of apartment boxes, malls, restaurants, and marinas full of boats of the mega rich. So that’s a complete transformation, and I think I actually prefer the old Costa del Sol, but nevermind it’s gone forever. And there were other places I went we used to call it the Third World. The West was the First World, Communist the Second, and the Third World was underdeveloped, very underdeveloped. Indeed the mercenary wars of West Africa were pretty barbarous. Now barbarity, you’ll find it in Syria with ISIL. So I just had this bump of curiosity. I just said to my dad, “Dad, I want to see the deserts, the jungles, the snows, the open oceans.” I wanted to see them. That’s what took me to all these places.

Can you talk about the transition going from a journalist, a foreign correspondent in war zones, and then becoming a novelist?

Well it wasn’t a conscious decision. It was fate and fortune yet again. I’d come back from Biafra. Third to last plane out. A fraught journey. I got back to London in the last days of 1969. 1970 dawned and I had no job, no prospect of a job. I’d been well smeared by the Foreign Office. I had no life savings, no apartment, I was sleeping on the sofa in a friend’s place. When they went off to work in the morning I would just think about what the hell to do. That was when I hit on the stupid idea really, of trying to write a novel. I say stupid because the odds were immense that it would ever get published. The whole history of novelists is fraught with drawers of rejection slips before the first break comes, if at all. But to be a major seller is weird. So I didn’t know these things. I was naivete personified. This story just happened to be something I’d worked out seven years earlier when I was a Reuters man in Paris in ’62, ’63. That was when the OAS was genuinely trying to kill Charles de Gaulle. Just watching from the sidelines, I worked out that they were not going to succeed, but they might if they brought in an unknown outsider with no dossier in police HQ, had never been seen before, nobody knew what his name is, what he looks like, but with rifle with a scope sight on it. That might work, thought I, but thought no more about it. Seven years go by, I’m sitting at a friend’s apartment in London thinking, “What am I going to write about?” Well I’ll write about this idea. So I just sat there and wrote for 35 days. I had nothing else to do. I wrote 12 pages a day, seven days a week. And that was the novel. That was how the transition was made. Even then it was only a manuscript. A lot of guys have a manuscript. I didn’t know what to do with it. I didn’t know how to approach a publisher, I didn’t have an agent. I just hawked it from publisher to publisher, and got rebuffed by the first four. Then my lucky break.

For Day of the Jackal and other early books you had your wealth of experience from your career to draw on. Yet you continued to do risky things. Was that to stay sharp for your writing?

You can really divide my career as up to Dogs of War and post-Dogs of War. I felt an obligation to research to get the facts right if I was going to pretend a gun works this way, or a fast sports car works this way, or a parachute works this way, I’ve got to find out. So up to a point, when you’re obscure you go to the authorities, they don’t know or care who the hell you are. And when it comes to criminality there are only two people who know about it. Criminals themselves and the police! Because they’re kind of partners in this weird dance-a-macabre. So if I want to get into the background of cocaine smuggling I could probably today go the DEA, and they’d say, well, we know who you are so what can we do? But back then, they didn’t know. That was why I ended up in 1973 in Hamburg trying to investigate black market arms trading. Now I’d go to the police, and they’d probably tell me. Or even the intelligence community, they’d tell me, “Well black-market arms trading is done here, here, and here by him, him and him.” But back then I went in to the business by the other end, by the criminals. That’s why I ended up being chased out of Hamburg by a thug. But that was probably the last time, I didn’t need to do that after that. I could go in the respectable end and get cooperation from the authorities. But that didn’t prevent me needing to see places I was going to describe. So I said, I need to see Kabul in Afghanistan, I need to see Islamabad, I need to see Mogadishu with The Kill List. I need to see places if I’m going to describe them accurately.

Is there anything you wanted to write about that you haven’t?

No. There are a lot of things I would be very bad at writing about—like romance.

I don’t know, there are some dalliances in your book…

Yes, but I think just touching on them is as far as I want to go! I am not a Jackie Collins, God bless her. I am not Danielle Steele. The great romantic novelists are usually women, although not always nowadays. My descriptive passages would be ludicrous. There are things you know you can do, things you know you can’t. So I would say the kind of writing I do is probably the only kind I can.

What about places in the world you really want to go?

Look, there is a place you may not have heard of called the Ningaloo Reef, off the coast of western Australia which apparently has the most amazing coral and you’re guaranteed to swim with a whale shark. As a scuba diver I never got to swim with a whale shark. I did with a giant manta ray, and various other kinds of sharks, but never a whale shark. But I think it would knock me out to get there, it’s so far. There’s coral in the islands of the South Pacific I would like to see. But nothing I really, really lust for. There are some things I look back in hindsight and wish I had. But I’m 77 now, stiffened up a bit, and I find 24-hour air journeys very exhausting. So I’ll probably take a rain check on the Ningaloo Reef and the South Pacific.

At a very young age, nine, you saw a man drown and he almost pulled you under. When you were a teenager you were nearly raped by an Algerian man. You saw people starving and dying in war zones. What kept you from being desensitized?

Well I’ve long taken the view that we journalists are not robots. It’s okay to say that you’ve got to be objective, you’ve got be detached, but up to a point. If we see a starving child and it means absolutely nothing to you, then something has already died in you. Because one is hopefully compassionate and there are horrible things to be seen in this world. I don’t see how journalists are to remain utterly unmoved. They are still supposed to, despite what they feel privately, turn in an objective report with the facts. At least that was the training I got at Reuters. But you can’t be just a pillar of stone where children are dying like flies all around you. If you’re going to be a war correspondent you’re going to see horrible things. But you don’t have to be block of ice.

I read the passage about the girl in Biafra asking you for food. What have you made of the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean?

These are war refugees. Some are and aren’t. Some are from Afghanistan. Some are coming from Iraq. They’re both failed states. They’re both awful places to live. There’s Somalia, Yemen consumed now by civil war. South Sudan after fighting for its independence for years and years and years. There’s Libya. We helped them get rid of their insane dictator and what do they do? They turn the place into a hell-hole. One looks at all these people coming out of Syria, but they’re really just the tip of the ice berg. There are huge tracts of the world that are destitute, dangerous, and failed. They were communities who got independence and then made a total dog’s breakfast of it. Thirty years ago they wouldn’t have known there was an alternative. But modern technology—they may be impoverished but they all seem to have an iPhone—and they can look at it and see another world. A wonderful world. A world of stability and human rights. Police who behave in a civilized manner, politicians who are democratically elected. Hospitals, schools, and pavements that are cleaned. They see this from their personal hell and think, I have to go there. It’s not going to be just Syrians. It’s going to be millions who will start moving to Europe if they are not already en route. And frankly, the European continent just can’t take them. It’s going to be the major crisis of our age, the age beginning around 2015 for the next decade or two. What to do? I don’t know. It’s a bleak prospect actually.

It’s worth saying that after meeting with that dying child I wrote some bitter passages about my own government which I do not withdraw. I think my country behaved in a disgusting way over that whole Nigeria-Biafra conflict. Just lied and lied and I will never forgive them for that.