Abdullah never gives up. The senior Taliban commander, who goes by one name, lost a leg in the fighting in late 2001 just as Mullah Mohammad Omar’s forces were collapsing. He was captured and sent to the U.S. lockup at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Released from the Cuban prison in late 2005, he was immediately rearrested when he arrived in Pakistan and spent the next five years in a Pakistani jail run by the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency. After nearly a decade behind bars, he was released in 2010 and quickly became the insurgency’s overall commander for the strategic region of southern Afghanistan. Pakistan’s release of Abdullah and of some two dozen other important Taliban prisoners in late 2012 was meant as a goodwill gesture to Kabul. Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s government has been lobbying Islamabad hard to get it to release top insurgent inmates like Abdullah as a means of luring the Taliban into peace talks. In theory, the freed prisoners were to rejoin their families, most of whom live in Pakistan, and to serve as harbingers of peace—not return to the 12-year-old jihad against the U.S. and Kabul.

That strategy seems to have backfired badly. So far the prisoner releases seem to have only succeeded in funneling commanders and fighters back to the fighting. Once freed, Abdullah and a slew of recently released Taliban inmates have made a beeline back to the battlefield. Abdullah tells The Daily Beast exclusively that he is now more committed than ever to the jihad. “We are born for jihad and can’t sleep without the jihad,” he says, after just returning from the front lines in southern Kandahar Province. “Long imprisonment hasn’t slowed down our momentum, resistance and commitment to the fight.” He says he is not grateful to Pakistan or Kabul for his release. “I’m not thankful to Karzai and my enemies in Pakistan for releasing me,” he says. He flatly rejected the verbal restrictions Pakistan put on him and the other prisoners when they were released: that they not return to the fight. “None of us would ever accept any conditions or restrictions that would keep us from fighting,” he says.

Even given the lack of success in keeping fighters out of the fray, Pakistan’s release of insurgent prisoners has continued. So far this year, at least 40 imprisoned Taliban of both senior and junior ranks have been freed. But the releases don’t seem to have won any Taliban hearts and minds—or to have induced the Taliban leadership to move any closer to peace talks. Any hope for a dialogue was further set back this past summer when the Taliban opened a quasi-embassy in Qatar as a venue for the fledgling talks, a move that provoked a furious Karzai to cancel any further official contacts with the Taliban.

Meanwhile, many of the more than 60 prisoners like Abdullah, who have been released over the past 13 months, seem to have quickly returned to the insurgency after brief visits with their families in Pakistan. “The priority is jihad not family and kids,” says Abdullah. A senior Taliban intelligence officer tells The Daily Beast boastfully that “almost all of the freed prisoners never lost faith in the jihad despite the hardship of prison and are back enjoying the struggle.” His unscientific guesstimate is that 80 percent of the released insurgents have rejoined the fight. As he points out, two the Taliban’s top commanders—Abdul Qayyum Zakir and Abdul Rauf Khadim—were both released from Guantanamo Bay some six years ago and are now directing the fight.

An Afghan government intelligence officer who is charged with following some of the recently freed Taliban expresses his disappointment at the results of the releases. He says Mullah Muhammad [he has no first name], a former insurgent shadow governor of northern Baghlan Province, was arrested in early 2010 along with Mullah Mohammad Omar’s deputy, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. After more than three years, Muhammad was freed from a Pakistani jail this past summer and is now a member of the insurgency’s governing council, the Quetta Shura, and has returned to running guerrilla operations in Baghlan once again. “We had been expecting them to be nice and to help restart the talks but so far we have not received any positive signals,” the Afghan intelligence officer says dejectedly.

Mullah Muhammad is but one of many. Mullah Abdul Bari, 45, a senior commander in southern Helmand Province, was arrested in Quetta five years ago during a night raid on his house by the ISI and spent hard time in the notorious Pakistani prison at Mach in Baluchistan Province. According to Bari’s close friend and fellow officer, Mullah Abdul Salam Khan, Bari was freed earlier this year at about the same time as another insurgent operative Mullah Nuru Din Turabi. “Bari had a black beard when he was arrested,” Salam Khan says. “But during that time in hell in Mach his beard turned pure white.” After his release Bari returned to his family for a few months to regain his health and then quickly rejoined the insurgency. “He started as an ordinary small commander,” Salam Khan says. “Now he is in charge of eight large units on the Helmand front.”

Salam Khan recalls Bari telling him after he was released that he has no regrets. “Jails, torture and suffering won’t change our jihadist commitment,” Bari told Salam Khan. Salam Khan should know. He was captured in Pakistan in 2009 while he was the shadow governor of southern Kunduz Province and was finally released by the ISI five months ago. After a brief visit to his family in Pakistan, he is now serving as the shadow governor of the key northern province of Balkh.

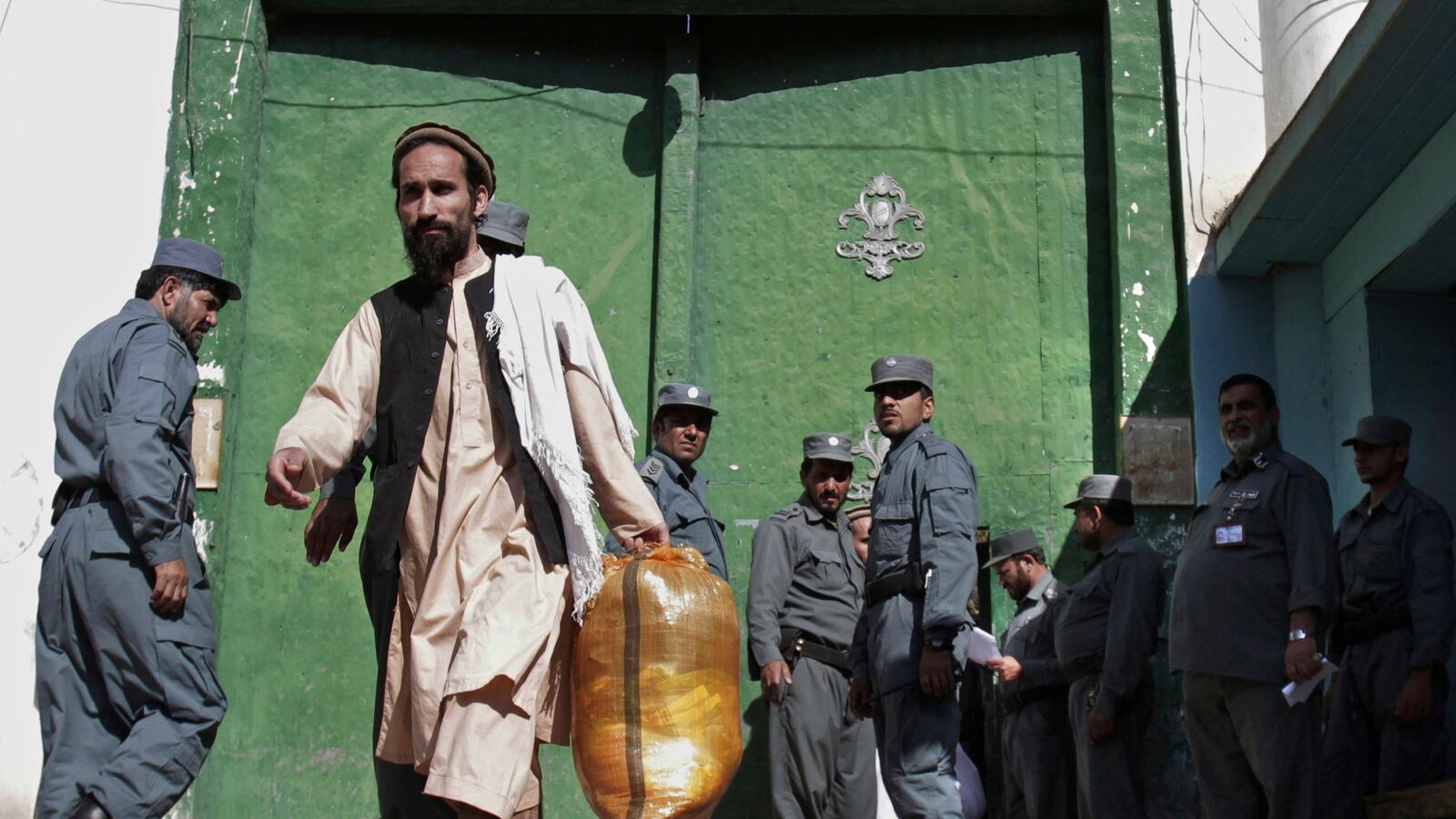

Another fast-rising former prisoner is Mullah Sadar Ibrahim. A former senior commander who was close to Mullah Omar, Ibrahim had been languishing in Pakistani jails for the past five years. He was released in late 2012 and has quickly garnered the senior posts of commander for military operations in several southern provinces, the Taliban’s former heartland, and is now also the deputy chief of the Quetta Shura’s important military council. Mir Ahmad Gul, the former shadow governor of Logar Province, just south of Kabul, who was recently freed after several years in a Pakistani prison, has been appointed shadow governor of the strategic region abound the eastern city of Jalalabad. Kabul, too, has been releasing Taliban prisoners with largely the same disappointing results. Two senior commanders named Abdul Wasai and Mullah Qasim Akhund were freed by Kabul last year. Both men had been imprisoned in the sprawling Pul-e-Charki jail near Kabul for several years and are now respectively serving as shadow governors of Kandahar and Ghazni Provinces. “Some of these former prisoners are now in key senior posts and many more have returned to being fighters and facilitators for our cause,” says the senior Taliban intelligence officer.

The Taliban intelligence officer says almost all of the former prisoners report that they experienced mental and physical suffering while in Pakistani custody. But he says those Taliban prisoners who were incarcerated in Afghan prisons serve relatively easier time than those held across the border by the ISI. Prisoners in Afghan jails, even Taliban, can periodically receive visits from their families and may even enjoy some protections under the Afghan justice system. In Pakistan, the intelligence officer says, Taliban prisoners simply disappear into a black hole with no possibility of contacting their families and no protections under the Pakistani constitution. “All of these men have been kidnapped by the Pakistanis,” he says. “It’s as if they no longer exist.” Not surprisingly, he adds, the released prisoners have little but hatred for their former jailers. “None of these men is going to join Karzai or stop contributing to the jihad,” he says. “They are now more committed to the fight than ever.”

While none of freed Taliban prisoners has brought the insurgents any closer to the negotiating table, Karzai seems to be obsessed with the belief that at least one prisoner, Mullah Baradar, Mullah Omar’s former number two, can somehow orchestrate a breakthrough. Baradar was arrested by the ISI in early 2010. Ever since then Karzai has been pushing Islamabad hard in order to gain access to him. Finally, reacting to Kabul’s entreaties, the ISI nominally released him this past September, but he apparently remains under house arrest in Pakistan. Late last month on a brief visit to Kabul, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, reacting to Karzai’s insistence, agreed to allow members of Kabul’s High Peace Council, the entity Karzai has designated to negotiate with the insurgents, to meet with Baradar in Pakistan. But after four long years in Pakistani custody it is unclear how much clout or credibility, if any, Mullah Omar’s brother-in-law retains with top insurgent decision makers in Quetta.

Afghanistan is betting heavily on Baradar as the key to peace talks. But this gamble may turn out to be just as big a loser as have all the hopes that Kabul has placed on prisoner releases so far.