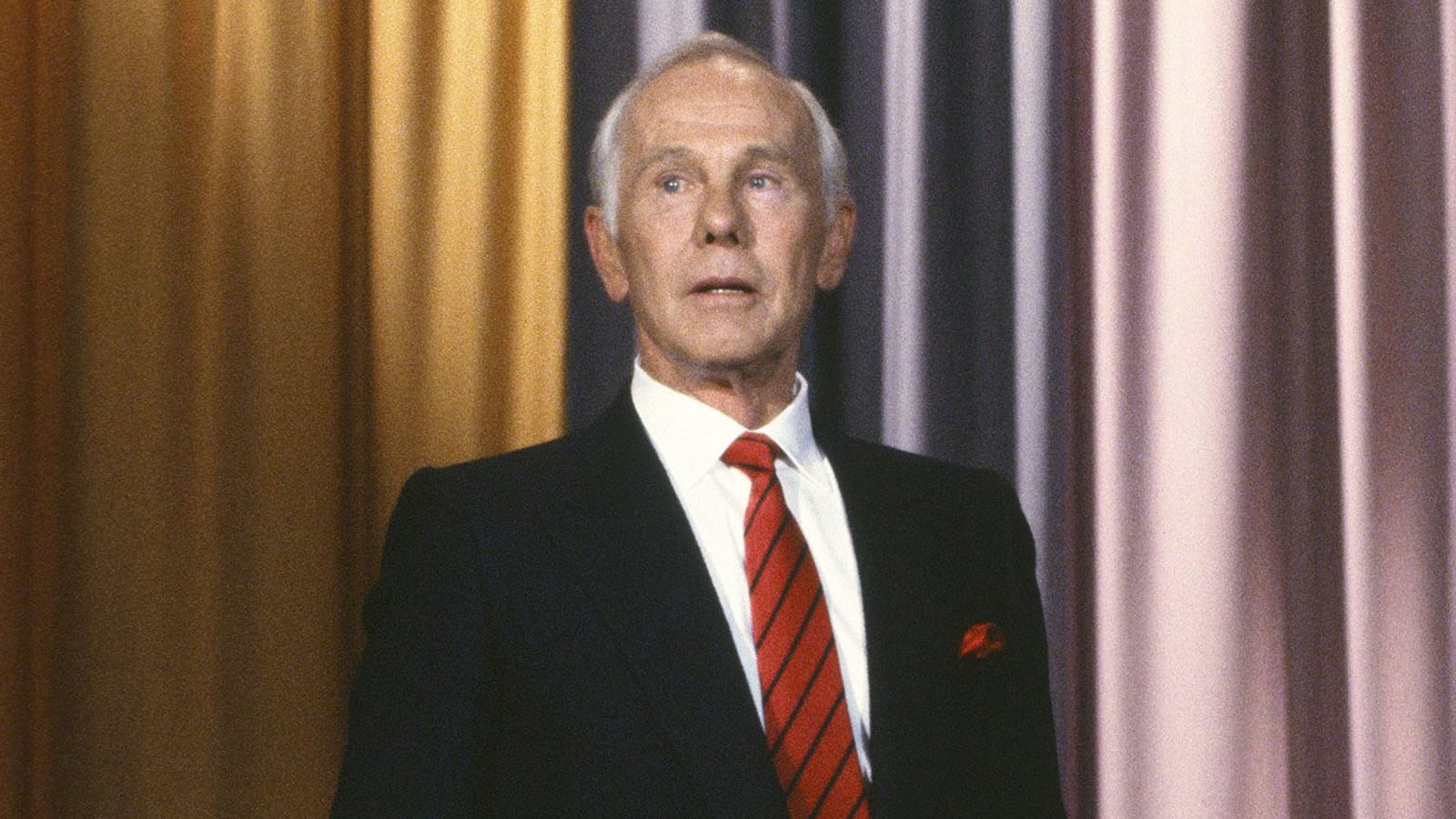

Nearly everything that happens in television happened before—and now, thanks to technological evolution, will happen again. Jay Leno isn’t the first host of The Tonight Show to log more than one fond farewell to viewers. Jack Paar, who not so much hosted as owned the show from 1957 through 1962, did a wrenching farewell when he left Tonight, and then did another one three years later when he departed a prime-time weekly hour also on NBC.

Fifteen years or so ago, I had the opportunity to tell Jack, who had miraculously become a friend, that if he’d stayed on the program as long as his successor, Johnny Carson, “we’d still be in Vietnam.” I was teasing Paar because his brand of combative, sometimes convulsive television stirred up passions rather than cooling them down; he went from controversy to feud to controversy, taking viewers for an incomparably wild ride that no one has ever equaled.

For some of us, all of late-night television since has been an aftermath to Paar (an after-Paarty?), but network executives were much happier with Carson, who for most of his tenure avoided turbulence as avidly as Paar created it. Sponsors disliked turbulence and the disruptive effect it might have on viewers, so not everyone lamented Paar’s exit.

Watching Paar do his last Tonight show was almost like witnessing an ascent into clouds. People wept, literally. But then Paar had always been openly teary himself. “Hell, I cry when I take the Coke bottles back,” he joked on his last Tonight show—a remark that generations who’ve popped the tops of throwaway cans won’t understand.

Having shoo’d all the other members of my family to bed, this loyal Paar fan watched and audio-recorded Paar’s last Tonight show in awe, genuinely saddened at his departure. Then again, I was barely out of puberty at the time. No one knew that Paar would make another emotional farewell, this time to series television, in 1965. Even his temperatures had cooled by then. He hosted the show from a seat in Studio 6-A, the lone member of his studio audience unless you count his beautiful German Shepherd Leika in the next seat.

After narrating a dazzling gallery of clips from past shows—everything from visits to Albert Schweitzer in Africa to the actual TV debut of The Beatles, via film shot in England weeks before their debut on The Ed Sullivan Show—Paar stood up, said, “Come on, Leika, let’s go home,” and walked out of the studio, the dog right behind.

Comedian-actor Garry Shandling thought that farewell to be so memorable that he studied videotape of it when preparing a faux-farewell for Larry Sanders, the talk-show host he played brilliantly for six years in the ‘90s on HBO’s innovative Larry Sanders Show. By then, emotional farewells had long since become established showbiz rituals, especially on talk-shows or variety shows where solo hosts presided.

If enough clips from a seeming infinite number of sources could be assembled, “The Farewell Farewell Special”—goodbyes going back as far as Fred Allen bidding adieu to What’s My Line? and continuing up through Leno Farewell No. 2—could conceivably be an entertaining hour or two of TV, especially now that looking back is facilitated by all the digitzed tape sitting around in storage or being perpetually recycled on cable and home video. Much of Paar is available on YouTube, but watching disjointed clips can only give a pale impression of what it was like to watch Paar nightly—from the edge of your bed, as it were—and to be a part of that happy madness.

Carson’s memorable (and, yes, iconic) farewell to the nation was reminiscent of Paar’s last Tonight show, except that Carson spread his out over two nights, not counting the year of tremulous dread that we Carson fans spent as the clock ticked toward the grim inevitable. Some of us got emotional when realizing we were watching the last “Aunt Blabby” sketch, and when Bette Midler dueted with Carson on his penultimate Tonight, we were awash in tears.

Perhaps we become more intimately involved with, and more vulnerable to, late-night personalities than with those in any other of the so-called dayparts that Madison Avenue has divided TV into. Even if there’s someone in bed right beside you, after all, David Letterman’s might still be the last face you see before sleep sets in.

What a tricky affair it will be when Letterman does his final Late Show, and from little signals he’s been giving off for some time now, that unhappy event is not all that dimly in the distance (it’s a foregone conclusion, by the way, that Leno will show up soon as a Letterman guest, though it could not be confirmed yesterday). Letterman’s entire career and persona were founded essentially on a rejection of show-biz sentimentality and phony emotionalism. He flipped all the schmaltz and hokum that had preceded him and made it work again, this time as the comic equivalent of, say, a photographic negative.

Will Dave be able to keep even his emotions tidily in check when he looks into the CBS cameras for the last time and realizes he won’t be returning to them, or vice versa? He feels as comfortable in their cool gaze as normal people do basking in sunlight, or in a loved one’s eyes. Letterman has, indeed, shown occasional emotional vulnerability, as when introducing “the doctors who saved my life” after his quintuple heart bypass early in the year 2000, but he may want to do his last show alone in a studio in the Paar and Carson tradition.

One of the many personalities who filled in for Letterman during his long recovery was, lest people forget, Jimmy Fallon, on whose relatively young shoulders the sacrament of The Tonight Show is very soon to descend. Pardon the hubris, but I told Lorne Michaels early in Fallon’s Saturday Night Live career that he could walk to another studio and host a talk show the very next night if one were offered him. Actually, Fallon didn’t do spectacularly well in Dave’s chair, but he seemed to be getting no help from Dave’s loyal staff, not one of whom would even tell Fallon that his shirt collar was sticking up almost in his ear.

But Fallon has it, that natural affability that is an absolute prerequisite for talk-show hosting success. Calling it “unnatural affability” is probably more accurate; it’s very unnatural, or else lots more people would possess it. In the first great generation of television personalities, many of whom simply emigrated from radio, there were many who seemed either to possess the gift (Dave Garroway) or to be possessed by it (Arthur Godfrey). You don’t remember them? They blazed the very trails that Fallon and Conan O’Brien and Arsenio Hall and all the others now tread upon.

“Show business” was much more a haven for sentimentalists then, not for ironists like Letterman or cold-blooded comics like Leno. Back in those days, the big big stars would say “farewell” rather than merely “good night” at the end of nearly every appearance, not just at a career crossroads. Comics had contrapuntally sentimental theme songs that would sneak in under their good-nights (and “drive safely’s,” as Letterman sometimes echoes) and help usher them off.

Milton Berle’s theme song was “Near You”: “There’s just one place for me, ladies and gentlemen, and that’s near you,” Berle would say, probably not realizing how pathologically accurate that sentiment was in his case. Jimmy Durante seemed to be trying to evoke tears at the end of every show he did, walking into the distance through pools of descending light and mispronouncing “au revoir” as “Ora-Vo” before “Good night, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.” Crazy how vividly one can remember crap like this, and I say “crap” only with the greatest affection.

It’s a weird and maybe silly fact that since media took hold of American life, people tend to love and cherish whatever television they grew up with. Thus were those so-called entertainment reporters pronouncing Leno’s bifurcated exit yet another “end of an era.” Those of us around for the beginning of all this know, however, that eras don’t end the way they used to. More often—but not as painfully.