On the final Saturday night of February, about 30 men, women and children shuffled into a dingy tenement basement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. They were there to pay their respects to a friend whose life had intersected with icons of art, music and literature but whose body was about to be disposed of in a mass grave before they’d intervened.

As the mourners arrived, some cracked open cans of Coors and Pabst Blue Ribbon. “To Hassan,” they said, as they poured a taste of each beer down a single drain that sits at the center of the basement’s concrete floor. Others lit joints and offered them around to the congregation.

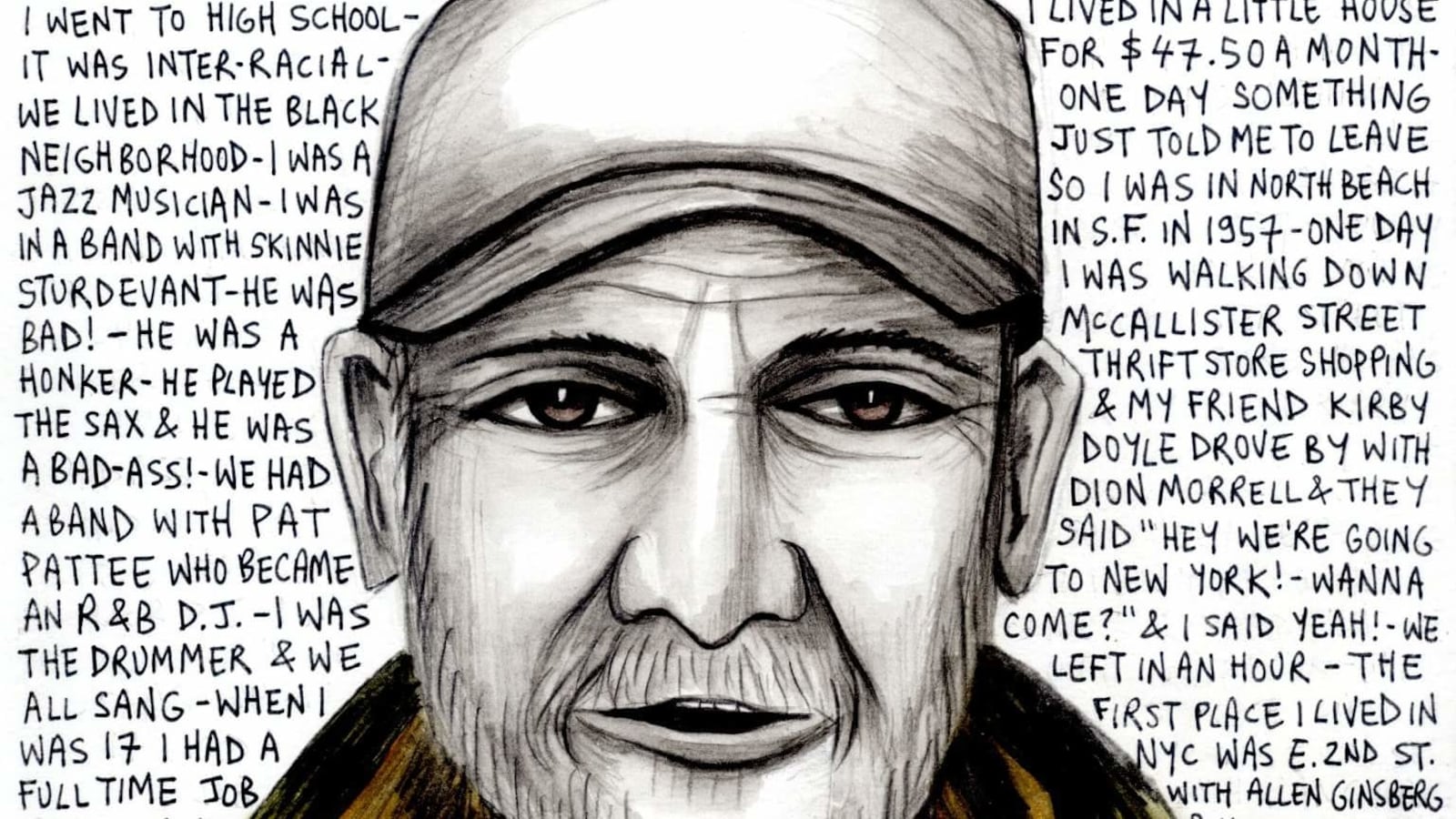

A table was propped up on a wooden stage that extends from the basement’s back wall. At the edges of the table were four lit candles, with burning incense sticks between them held in place by beer can tabs. A bottle of Palo Viejo rum sat in the middle of the table, in front of a book for attendees to write their memories of Hassan Heiserman, the man they had come to mourn.

Photos were taped around the basement’s graffiti-covered walls. One, taken by the poet Allen Ginsberg, shows Hassan with a group of Beatniks in Portland, Oregon.

Philip Whalen, Jerry Heiserman (Hassan later as Sufi) & poet Thomas Jackrell who drove us Vancouver to San Francisco returning from poetry assemblage, we stopped to sightsee Portland where Philip had gone to Reed College with Gary Snyder & Lew Welch. End of July 1963. Vancouver. (Photo by © Allen Ginsberg/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

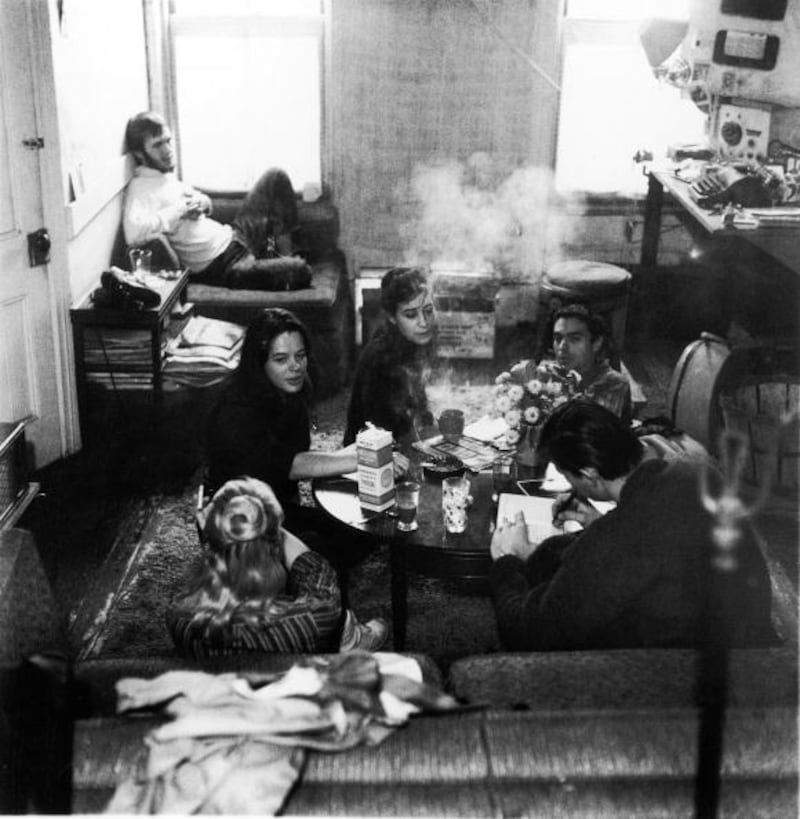

Allen Ginsberg LLCAnother, titled “In A Beat Pad” by Getty Images, showed Hassan lounging on a sofa in 1959 Greenwich Village. Others showed him in the same dank basement where his friends had now gathered, and where he had lived for more than a decade in the later years of his life.

A group of beatniks sit in an apartment (24 Cornelia Street), New York, New York, December 5, 1959. Pictured, foreground from left, Dian Doyle and Kirby Doyle (1932 - 2003); far side of table, from left, Mimi Margaux, Stella Pettelli, and Philip Lamantia (1927 - 2007); and Jerrold Heiserman (next to window). (Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images)

Fred W. McDarrahA handful of Hassan’s close friends went up on the stage to talk about him. One of them, a middle-aged man with an eyepatch underneath his glasses who gave his name as Popeye, put an index finger into the air for emphasis as he shared a story.

“I met Hassan in the ’80s; at that point his career included every fucking bohemian scene,” Popeye said. “He didn’t like to be called a Beatnik because he wasn’t a Beatnik. He didn’t like to be called a hippie because he wasn’t a hippie. Punk rock? Nah. He was a bohemian. He had been through it all.”

When it comes to Hassan Heiserman, who died in early January at the age of 77, the photos and the speeches shared that night were just a glimpse of his more than six decades around various counter cultures, including the jazz and downtown music scenes along with the beats and hippies and punks.

For all of it, Hassan was there on the periphery or, as he preferred to be, quite literally in the driver’s seat—a sort of outlaw version of “Forrest Gump” who loved to share his tales, especially when a can of beer was on offer.

Hassan was born Jarrold Jay Heiserman in 1940 in a small town in southwest Idaho. His parents divorced before his third birthday and he moved with his mother to Portland, Oregon.

When Jarrold was a young child, Hassan would later claim, he was placed in a children’s home while his mother, Frances DeLange, worked in a shipyard. “It was torture,” he said. “I was abused like a motherfucker!”

Jarrold was back in the family home by the time his mother remarried in 1945. With her new husband, she gave birth to Heiserman’s sister, Rebekah Ballard, in 1950.

Rebekah, now a grandmother living in Portland on disability, fondly remembers her brother Jarry during his early teenage years. At Tigard High School outside of Portland, he played drums, excelled in gymnastics and even joined the school’s cheerleading squad. As a teenager, he also bought his first car, a memory that would stick with him some 50 years later. “In 1954, dig this: I got a fucking car! A 1937 Chevy that I bought for $35,” he told a friend during an interview in 2010.

A few years later, he left home for San Francisco’s North Beach, seemingly without purpose. There, denizens of the Beat Generation including Jack Kerouac and Kirby Doyle made his acquaintance.

“Charlie Parker had just died. Dylan Thomas had just died. Walt Whitman just died. James Dean just died. It was the end of this era where the heroes to these poets died, so they wanted to live out the unfulfilled dream of all these wonderful people,” he said in an interview with a friend in 2010.

“I was a poet. I set up shop in an alley and I started painting and doing wild paintings on this wall with poems next to them. This is 1957 or 1958. This was before all the hippies, the long hair, the beards,” he continued. “I bought all my clothes at a thrift shop on McAllister Street. So I would wear these old fashioned suits, a hat, collarless shirt, and had really long hair. So people were constantly taking pictures of us. Playboy Magazine did a big article where they put a picture of Kirby Doyle and I… Kirby Doyle called me one of the ‘dandies’ of the era.”

Kerouac found Heiserman so compelling that he made him a character in his 1962 novel “Big Sur,” changing Jarrold Heiserman to “Joey Rosenberg” and describing him in the author’s trademark run-on sentences:

Suddenly appears Joey Rosenberg a strange young kid from Oregon with a full beard and his hair growing right down to his neck like Raul Castro, once the California High School high jump champ who was only 5 foot 6 but had made the incredible leap of six foot nine over the bar! … A strange athlete who’s suddenly decided instead to become some sort of beat Jesus and in fact you see perfect purity and sincerity in his young blue eyes—In fact his eyes are so pure you dont notice the crazy hair and beard, and he’s also wearing ragged but strangely elegant clothing … And I ask Dave Wain about him: Dave says: “He’s one of the really strangest sweetest guys I’ve ever known, showed up about a week ago I hear tell, they asked him what he wanted to do and never answers, just smiles—He just sort wants to dig everything and just watch and enjoy and say nothing particular about it—If someone’s to ask him ‘Let’s drive to New York’ he’d jump right for it without a word…

Heiserman got just that invitation, he later recalled, when he was thrift shopping on McAllister Street. By then, it was the late 1950s and the center of the Beat movement was shifting from the west coast to New York. “My friend Kirby Doyle drove by with Dion Morrell and they said, ‘hey we’re going to New York! Wanna come?’ And I said ‘Yeah!’ We left in an hour,” he would tell a friend years later.

Once in New York, he lived with Ginsberg and two other Beatniks, Herbert Huncke and Peter Orlovsky, on East 2nd Street in the Lower East Side. Kerouac came around a lot in those days, he said. “He was always drinking and used to sing Frank Sinatra songs all the time.”

Like many of the free-wheeling Beatniks, Heiserman bounced back and forth between California, Portland and New York throughout the 1960s.

Back then, Portland was “backwater,” said Heiserman’s friend from the time, Maryalice Cheeseman, who is now 78 and still lives there. But when he would suddenly appear in the city, he would bring souvenirs from his travels elsewhere: new vinyl records, a new car—and perhaps most exciting of all, new drugs.

“He just would appear and do something amazing,” Cheeseman said. One time, she fondly recalled, “He brought an entire trunk full of peyote buttons, at a point when nobody used any kind of drugs other than a little pot. He got them from some place in Texas that sold them by the guinea sack full.”

“When I was in labor with my first child he actually took me to the hospital. He was driving a 30-foot van full of drum sculptures and methedrine” she recalled. “Somebody had inherited a bunch of money and they loaded the van with [speed], so they’d have a lifetime supply.”

In New York in the ’60s, Heiserman got into similar shenanigans. At his memorial, a friend read an excerpt from another interview he later gave:

I came back to New York, I got involved—we were kind’ve a gang. We ran with this guy named Turk and (another one named) Mickey Lee. Both Turk and Mickey Lee had just gotten out of the Marines. Mickey left AWOL. And then with this black guy from D.C., his name was Speedable. Turk, Mickey Lee and I, and a big fat guy named Porkstack. That was his name. We were a gang…

We were doing mad shit, stealing cars. And once we stole this car, and we had it for a couple of days, a station wagon. And we pulled right up to MacDougal Street near Washington Square Park at 6 o’clock in the morning. Turk put a lit cigarette in the gas tank, and it blew up. There was this gigantic fire and we just went into the park and sat on a bench, like we didn’t know that the car just blew up.

There was this big, tall Irish cop. I think his name was “Eddie The Cop” or “Jimmy The Cop,” something like that. And he got it into his head that we had arranged to have this thing blown up. So he had us picked up once or twice, and he says to the judge, he says: “Your honor, I have reason to believe these people are marijuana addicts. They’ve been in the park all hours of the day and night and blah blah blah.”

The story was cut off there, as a toddler at the memorial interrupted. “Hi! Nice to meet you,” the child said to the reader, and the crowd erupted into laughter.

In any event, Heiserman seemed more partial to driving cars than burning them. In the ’60s, driving became his calling and remained a constant in his life. Whether it was for a friend in labor or for stars of American literature and music, he always wanted to be behind the wheel.

In the mid ’60s, Heiserman was in Los Angeles, driving for The Byrds right around the time their hit song “Turn! Turn! Turn!” was released. Heiserman’s sister Rebekah remembers visiting her brother in LA at the time and being brought backstage at Whisky A Go Go in Hollywood during a show.

“He took me to see them and to the dressing room to meet the band and hang out in between sets,” she told The Daily Beast. “It was pretty amazing for a kid to meet a big band like they were.”

By the late ’60s, he drove in New York for music producer Alan Douglas, who produced records by Jimi Hendrix, Duke Ellington, and Charles Mingus, among others.

“It would’ve been like, ‘[Heiserman], go get Jimi. We got to take him to the studio. We have to pick up these tapes,’” recalled Bill Laswell, himself a prolific music producer and bass player who would later make use of Hassan as a driver.

“Alan’s wife had a store in the East Village. She was Moroccan, so they would bring all the stuff from Morocco. [Heiserman] was the cleanup guy for the store,” Laswell said. “He would open the door for Hendrix, for Santana, Miles—whoever was coming around buying Moroccan clothing.”

“There was a lot of drugs in that scene,” Laswell added.

Heiserman also became interested in a movement called Subud, which was started by a Muslim spiritualist in Jakarta in the early 20th century, his sister said. Around the time President Richard Nixon declared his war on drugs in 1971, he started traveling east, visiting Indonesia and Turkey. Jarrold became Hassan, and he would go on to espouse Sufi Islam for the rest of his life.

“I traveled. Lived in the jungles of Java, Indonesia, lived in Turkey, Hong Kong, Singapore, Istanbul, Afghanistan, New Delhi,” Hassan recalled in an interview with a friend in 2010. “New Delhi was a very important part of my life because I met my Sufi master there. In Turkey I became involved with the Mevlevi and Bektashi brotherhoods, and in traveling to India I met Qadri-Chisti masters who had extraordinary powers, which I witnessed in many instances. I became spellbound by this phenomenon so subsequently I traveled the planet a number of times.”

From the mid-’70s through the mid-’80s, Hassan plied his two trades of driving and drugs. He acquired a New York City cab license and began to drive full time. On his off hours from the cab, he hung out in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village and sold ecstasy at city nightclubs. He didn’t put much stock in material goods—friends recalled that he owned maybe one bag stuffed with clothes, and would crash at different apartments and record studios around New York.

What Hassan cared about was being around the action, whether it was with musicians, artists or writers. He found his way there as a driver and as man with a reputation for locating whatever was needed to keep a party going.

“Hassan was always the guy who would facilitate things... if you need whatever drugs or somebody needs alcohol or food,” recalled Laswell, who met Hassan in the late ’70s and employed him as a driver on-and-off for more than a decade.

Hassan knew when and where he needed to be to make sure people got to their desired destinations. Even if that person was Miles Davis. “Every night Miles Davis would make a drug run. And Hassan would position himself in his cab up on 70 something on the west side and would make sure that he was at the corner,” said Laswell. “So he got to know Miles and he would take him to get his stuff and drive him back home, pretty consistently for quite a long time.”

While Hassan was using drugs in those years, his habit wasn’t debilitating. “I don’t think that part affected what he did,” Laswell said. “I thought that kind’ve kept him even to be honest.”

By the late ’80s, the Beatniks had long since given way, and a hodgepodge of teenage runaways, hardcore punk fans, artists, anarchists and people just looking for affordable housing began to take over vacant apartment buildings in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As New York’s squatter movement was born, Hassan was a natural fit.

He began spending time in the squats not because he had any political motivation to reclaim vacant apartment buildings. Rather, he identified with young people on the outskirts of society.

“He wasn’t a part of that construction or building or taking of spaces,” said Seth Rosko, now 42, who met Hassan in Lower East Side squat in 1989. “He wasn’t a part of the squatter movement. He just happened to be on the periphery of it and it took him in when he needed it.”

He needed it in part because drugs had become a problem for Hassan by the ’90s. He fell out of touch with Laswell and the other musicians and producers he’d used to drive for, and ended up homeless on the streets of the Lower East Side.

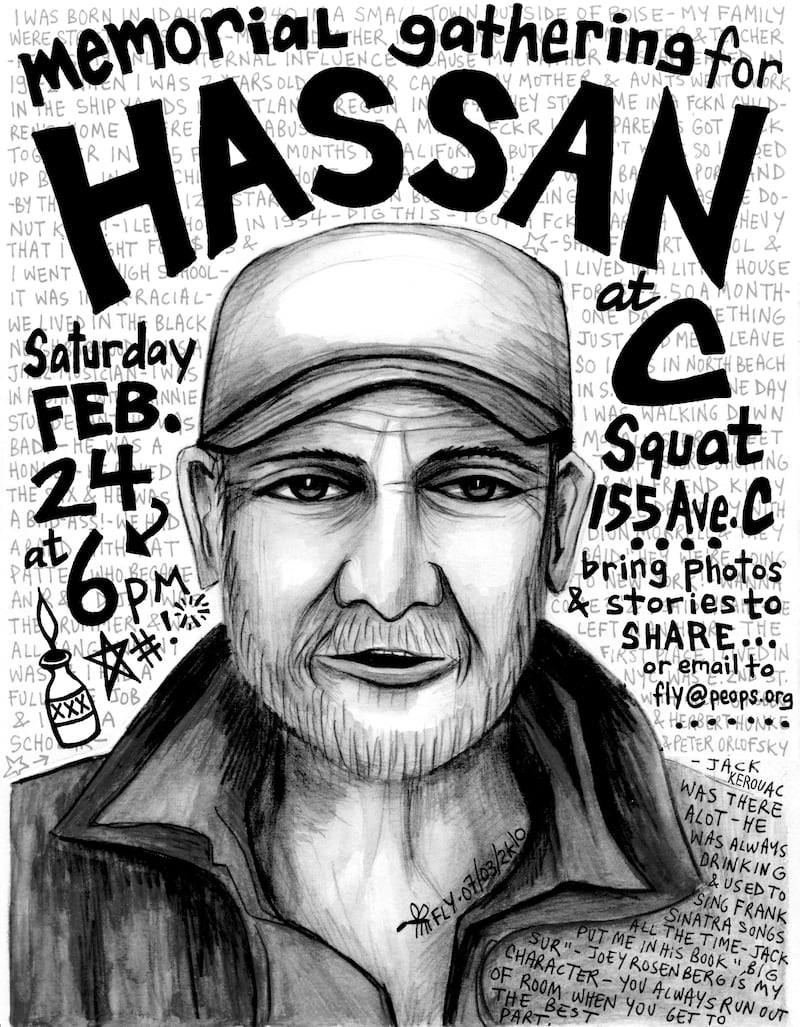

That’s were squatters found him in the early 2000s and brought him to what became his home: C-Squat, at 155 Avenue C just off East 10th Street. The tenement, then one of the most famous squatted buildings on the Lower East Side, is now one of 11 former squats that were brought up to code and became a legal low-income co-op.

“C-Squat is a real phenomena,” Hassan said in a 2010 interview with fellow resident Bill Cashman. “You just stay for a few days and keep track of the people that come and go here. You'll see an incredible variety of people that visit. The backdrop for most of it is laughter. There's a lot of laughing going on in this building. That's the truth.”

At C-Squat, Hassan was a grandfatherly figure who fit right in with the younger generation of outcasts, according to his housemates from the time.

It was there Hassan was introduced to the artist Dash Snow, dubbed one of “Warhol’s Children” by New York Magazine in 2007. Snow, who died of a heroin overdose in 2009, would go on to feature Hassan in a series of photographs for an exhibition.

“He did this art show where the whole space was photos of Hassan,” said Seth Rosko, who was a friend of Snow’s at the time. “He paid him to sit in the middle of the gallery and basically told stories. He called him papa smurf because of his hair.”

Other artists, too, featured Hassan in their work during his time at C-Squat. A video shows Hassan on stage at the Music Hall of Williamsburg, introducing the C-Squat- based punk band Leftover Crack before a show in 2011. Another band, Alienz, immortalized him with the “Hassan Song.”

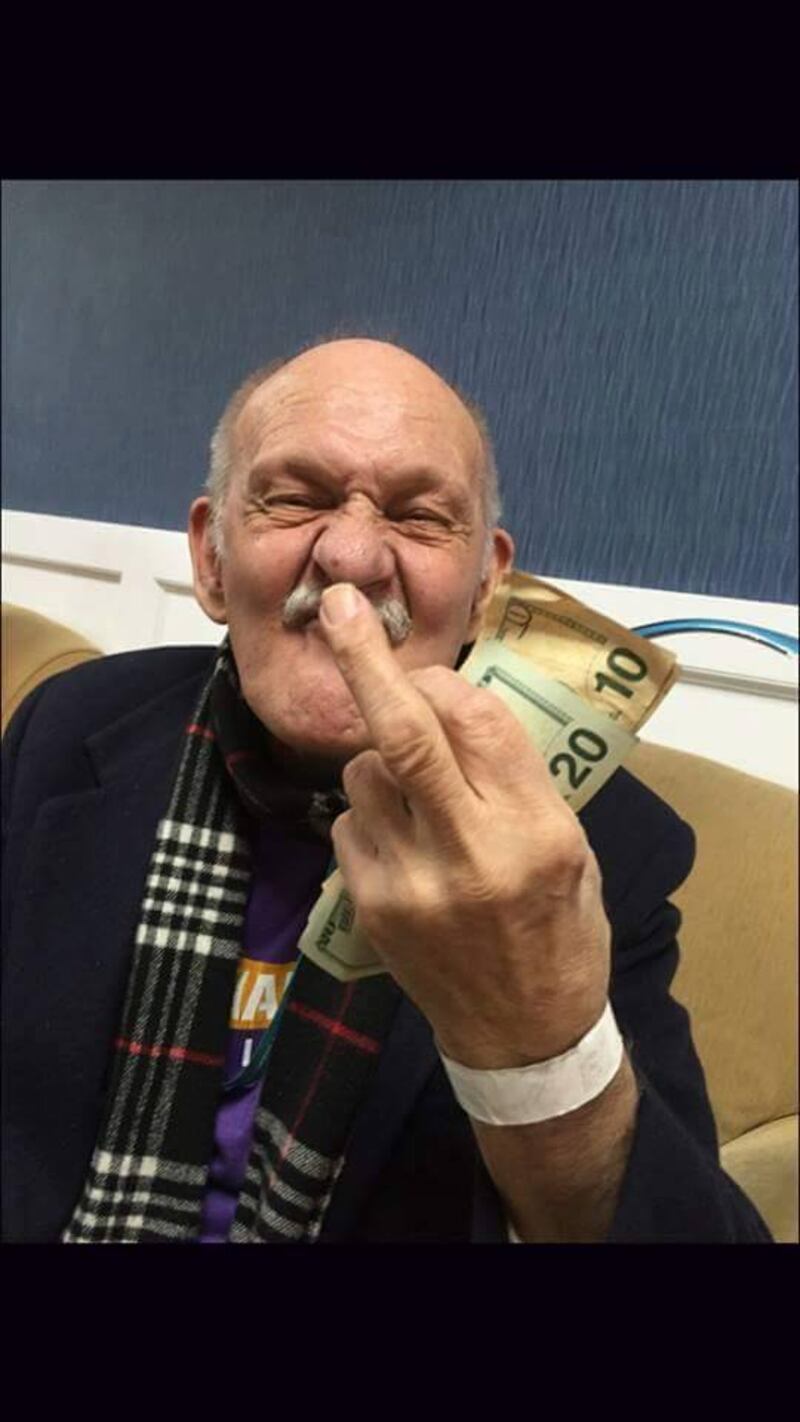

He became the unofficial doorman of C-Squat, known to perch on the stoop in front of the building with a can of beer, asking passersby for a dollar. He wasn’t the most effective barrier, friends recalled, and would let in the building anybody who offered him a dollar or a beer.

The habits that had left him out on the street remained with him in those years inside of C-Squat. A resident remembered other drug users from the neighborhood rummaging through Hassan’s pockets after he had passed out in a heroin or alcohol-induced haze. He collected Social Security by then, and the neighborhood junkies knew when he might have cash from his check.

Finally, C-Squat residents decided it was time to get him help. In 2014, they helped move Hassan, then 74, out of the building and into a program for elderly homeless New Yorkers. He moved around several nursing homes and assisted-living facilities in Bronx, eventually landing at the Bronxwood Home For the Aged.

His C-Squat family continued to visit him until his death.They sent him cards during the holidays, and even sprung him from those facilities and propped him up in front of C-Squat for birthday parties. He was sober for the first time in years and lucid enough to keep telling his stories, they recalled.

It was at a hospital near Bronxwood where Hassan, who’d had heart-related health problems, died on Jan. 3 after a blood clot formed in his leg. A holiday card from a former C-Squat resident was returned with a notice from the New York City’s Medical Examiner’s office announcing his death.

The memorial in C-Squat’s basement that Saturday was planned by current and former residents and funded through a GoFundMe page. It was covered in the neighborhood newspaper The Villager, with the memorable headline Hassan, C-Squat Sufi-hipster, 77, moves on to the next realm.

The money raised also saved Hassan from being buried in a mass grave on Hart Island in New York. Instead, the residents had him cremated. They plan to spread some of his ashes at C-Squat and send the rest to his sister in Portland.

At the memorial, they sketched his life with photos, a reading from “Big Sur” and even played jazz music in a space known almost exclusively for punk rock.

That Kerouac run-on, quoted above and read at the memorial, runs on, with his friend Dave still talking about Hassan and then the author’s stand-in picking up:

“On a sort of pilgrimage, see, with all that youth, us fucks oughta take a lesson from him, in faith too, he has faith, I can see it in his eyes, he has faith in any direction he may take with anyone just like Christ I guess.”

It's strange that in a later revery I imagined myself walking across a field to find the strange gang of pilgrims in Arkansas and Dave Wain was sitting there saying, "Shhh, he's sleeping," "He" being Joey and all the disciples are following him on a march to New York after which they expect to keep walking on water to the other shore…