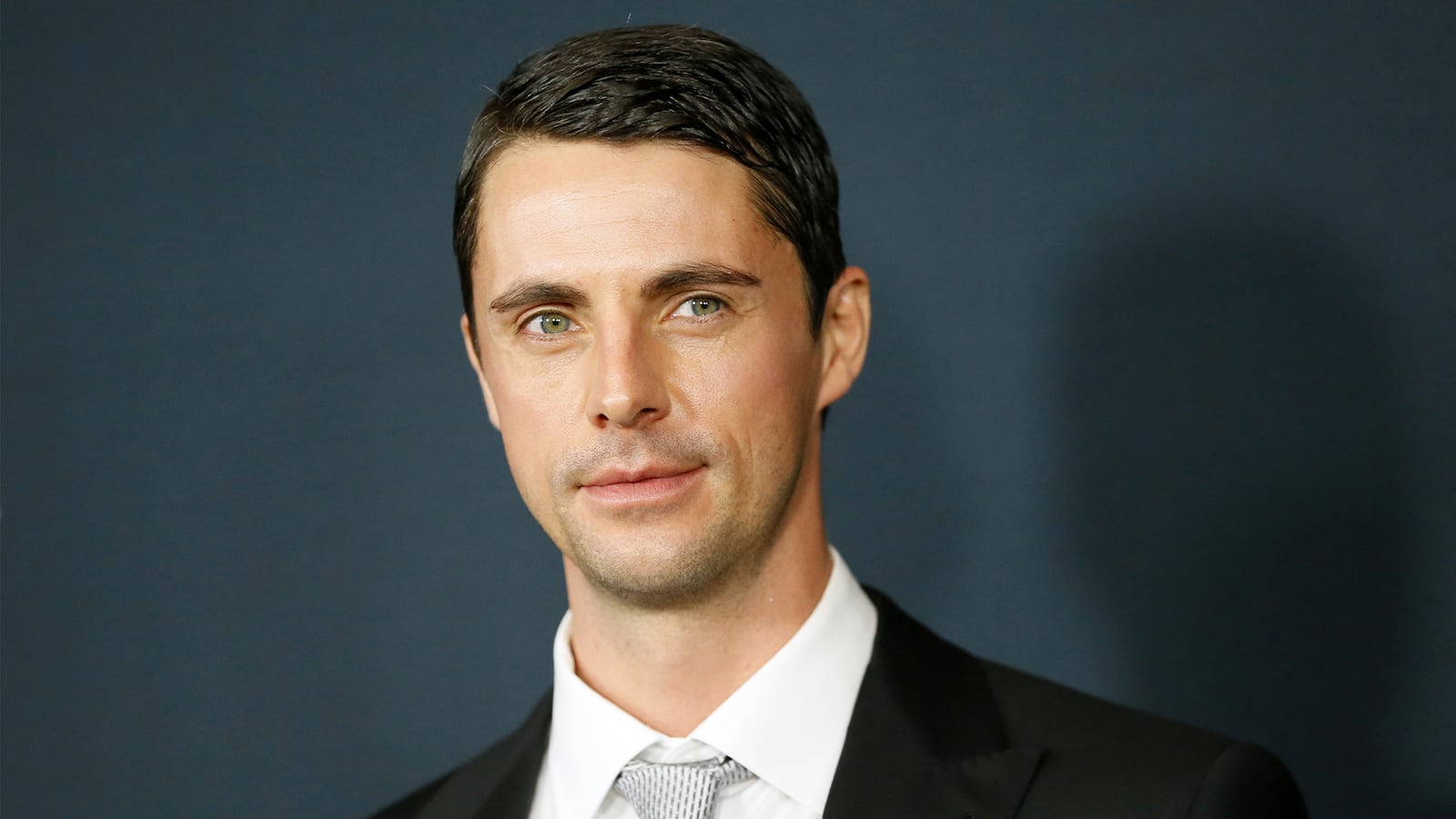

It takes an exceptional kind of actor to make Good Wife fans forget about their beloved Will Gardner, or to hold his own opposite “the Internet’s boyfriend,” Benedict Cumberbatch. But then again, it’s hard for Matthew Goode to turn off his charm.

It’s a special blend of self-deprecating humility and crisp erudite ease accentuated by the utter Britishness of his features, which epitomize the oft-used—though never this perfectly—label of tall, dark, and handsome.

It’s a kind of chameleonic charm, that can shade from dashing (The Good Wife or 2009’s A Single Man) to cunning (Woody Allen’s Match Point or the BBC miniseries Dancing on the Edge) to sinister (last year’s thriller Stoker) to all three (2009’s Watchmen)—transformations all underwritten by an unshakable charisma.

That charisma, too, is at the heart of his turn in the upcoming Oscar contender The Imitation Game, the alternately inspiring and tragic biopic of Alan Turing, the recluse cryptologist who helps Britain crack Germany’s Enigma Code in World War II and who is later criminalized for homosexual acts and commits suicide in shame.

Goode stars opposite a spellbinding Benedict Cumberbatch, who plays Turing, as Hugh Alexander, a British chess champion and mathematics whiz who was Turing’s biggest enemy and greatest friend at Bletchley Park, where they worked together on the top secret codebreaking team.

Alexander is everything Turing is not—gregarious, flirty, and, you guessed it, charming. Almost impossibly charming, in fact. So charming that you might watch the film and think that there’s no way the real-life Hugh Alexander could be that slick.

“He was extremely charming and urbane,” Goode stresses, during an interview about his turns in The Imitation Game (out Friday), The Good Wife (which aired its midseason finale Sunday), and his queer-friendly filmography (spanning his entire career).

Like any good actor, Goode nosedived into the real-life of the man he’d be playing, a math genius so talented that his work for British government is said to have led him to an early death. “The amount of literal brainwork needed to do his job too such a toll on him that it sent him to an early grave,” Goode says.

And while Goode maintains how the film portrays the schizophrenic relationship between Alexander and Turing, which vacillates between volatile and chummy, and Alexander’s boundless cleverness certainly ring true to the real person, what ends up being one of the character’s defining character traits in the film still bothers him: the description in the film that Alexander is “a bit of a cad.”

“I was slightly concerned about his being portrayed so much as a cad—though it was fun to do—because he was married to a lovely lady called Edith,” Goode says. “And one thing you do when you have to portray a real person is you’re sitting there going, fuck, I really hope this isn’t going to upset the family.”

What a gentlemanly, charming thing to say. Obviously.

The charm continues when we talk about how he got the role. He was juggling bags of groceries from Sansbury’s and trying to escort his “quite heavily pregnant” wife (his words) inside their home in the pouring rain when Cumberbatch himself called to offer him the role. “I said, ‘Yeah. Absolutely. Can I phone you back in a sec? I’m thrilled. But can I just get my family inside?”

The charm continues when he waxes on—and on—about the immeasurable respect he has for Cumberbatch, his friend of over 15 years. “I could lie!” he laughs. “‘Bloody awful! Smells a bit funny! Awful teeth.’ But it’s just not true.” I ask if he ever had his eye on Cumberbatch’s juicy Turing lead role. His humility in response is almost impossible. “I would never expect to be in the running in the first place,” he says. “At the same time, I’m the first person to recast myself out of any role. If you speak to my agent, it happens continually.”

And the charm continues even when we begin talking about the controversies that have arisen surrounding the film since it first began screening at festivals this fall. As mentioned before, Turing’s story is a tragic one. He was one of tens of thousands of British men who were criminally charged for suspicions of homosexuality and chemical castrated as punishment. The Imitation Game bookends its narrative with the damning, ultimately fatal effect this took on Turing’s life—but never explicitly shows Turing having gay sex.

There were reports that an earlier version of the script had a gay sex scene that was removed from the film. Cumberbatch and the film’s director, Morten Tyldum, both defended the reasons why there was no sex scene in the finished movie. A debate waged if this was a mountain being made out of a molehill, or an important cultural conversation about a potential Oscar-winning movie.

“You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t,” Goode says, when the conversation turns to the controversy over including a gay sex scene. “I’m glad that we didn’t. There’s many things we tried to get right, and I think it would’ve been too far, in the first film. I’m sure there will be other films about Turing that are ‘braver.’ But for bringing this story to a greater audience around the world, I think we gave him a film that he deserved.”

And Goode knows a responsible portrayal of gay character, having made queer turns in Brideshead Revisited, A Single Man, and Watchmen.

He is so refreshingly unfiltered and thoughtful when we begin talking about other issues surrounding the gay community and the entertainment industry (on demanding actors come out: “I think we need to stop demanding it and get over it;” on his career in gay-friendly films: “things have gotten more intelligent and more lucid and more interesting, but we still haven’t gone far enough) that when he begins to get cagey when we start talking about his arc on The Good Wife, it’s a little bit jarring.

Over the course of 17 episodes on The Good Wife, Goode’s suave lawyer Finn Polmar has quickly become a fan-favorite character. So favorite, in fact, that fans are doing the impossible: rooting for a romantic relationship between him and their beloved Alicia, a character who they’d previously rather see never love again following the death of her soul mate, Will Gardner (played by Josh Charles).

There have been teases of a future for the two—a lingering glance here, a quick hand hold there—but pressed on whether that spark will ignite into something more substantial, Goode goes numb. Though he says he has no other recourse.

“I’m as in the dark as the audience, which in some ways is frustrating, occasionally, but is also quite exciting,” he says. So the Alicia/Finn will-they-won’t-they? “I couldn’t give a definitive answer if I wanted to.”

Robert and Michelle King, The Good Wife’s showrunners, indeed, are notoriously secretive. (Remember when the show’s romantic lead was killed off the show and no one had a damned idea it was coming?) Earlier this fall, they were characteristically coy about the future of Finn and Alicia, even hinting that they weren’t sure where the relationship was headed.

“There’s an amazing chemistry between Julianna Margulies and Matthew Goode, and that comes through in the dailies,” Robert King said. “What you always want to do is react to the dailies to see where actors seem like they’re having the most fun.”

But Michelle King was quick to caution: “With everything we do in this show we really try to adhere to what would be psychologically true with Alicia. So we’re very sensitive to her probably being a little bit shy about rushing into things and yet being a vibrant woman. Those two things are in tension with each other.”

What Michelle is referring to, “what would be psychologically true,” is how quickly or believably she could move on from her great love with Josh Charles’s Will Gardner, regardless of her chemistry with Finn.

“It’s an impossible thing to try and replace, covertly or uncovertly, the kind of relationship that she used to have with Josh Charles’s character,” Goode says. Pressed for more, he cages: “I’m just excited to see where it goes.”

“It’s nice to be one of the few characters who’s not arch, or switching sides,” he says. “It will be the case of can the man and woman just be friends, in the answering of the question from When Harry Met Sally.”

Well, how typically charming.