Magazines, of course, have personalities. We bring a similar mental apparatus to a favorite magazine’s newest issue that we do to a meeting with an old friend. We prepare, unconsciously, for the contours and the colors, the particular set of authors, the style of the prose, the fonts, and the layout—the familiarity of a friendly voice. We expect novelty and surprise—but we expect them to unfold within a unique and essentially unchanging set of parameters. And, like people, magazines manifest their personalities in outward ticks that indicate but do not fully explain, or encompass, all that goes on inside. Time’s red border, The New Yorker’s staid blocks of diaeresis-dotted text, Harper’s index: these are more than frills—they are signifiers of something fundamental.

When, in the summer of 1969, three recent Harvard grads came to New York to start a humor magazine, they set about figuring out what sort of personality it would have. Henry Beard and Douglas C. Kenney, who had just written a bestselling book parody called Bored of the Rings, and their business-genius friend, Robert Hoffman, had many different ideas. They wanted their magazine to be slick and glossy, but also hard-edged, like the underground newspapers popular in the counterculture. They wanted it to be a bit like the hugely popular magazine parodies—of Life and Playboy and others—that they had recently put out as students at The Harvard Lampoon and that had made a lot of money. They wanted their new magazine to make a lot of money. They wanted it to be a bit like the old New Yorker, a journal arising from of a milieu of sophisticated wit, and to take on, and be a product of, the world around it. Most of all, they wanted it to be funny.

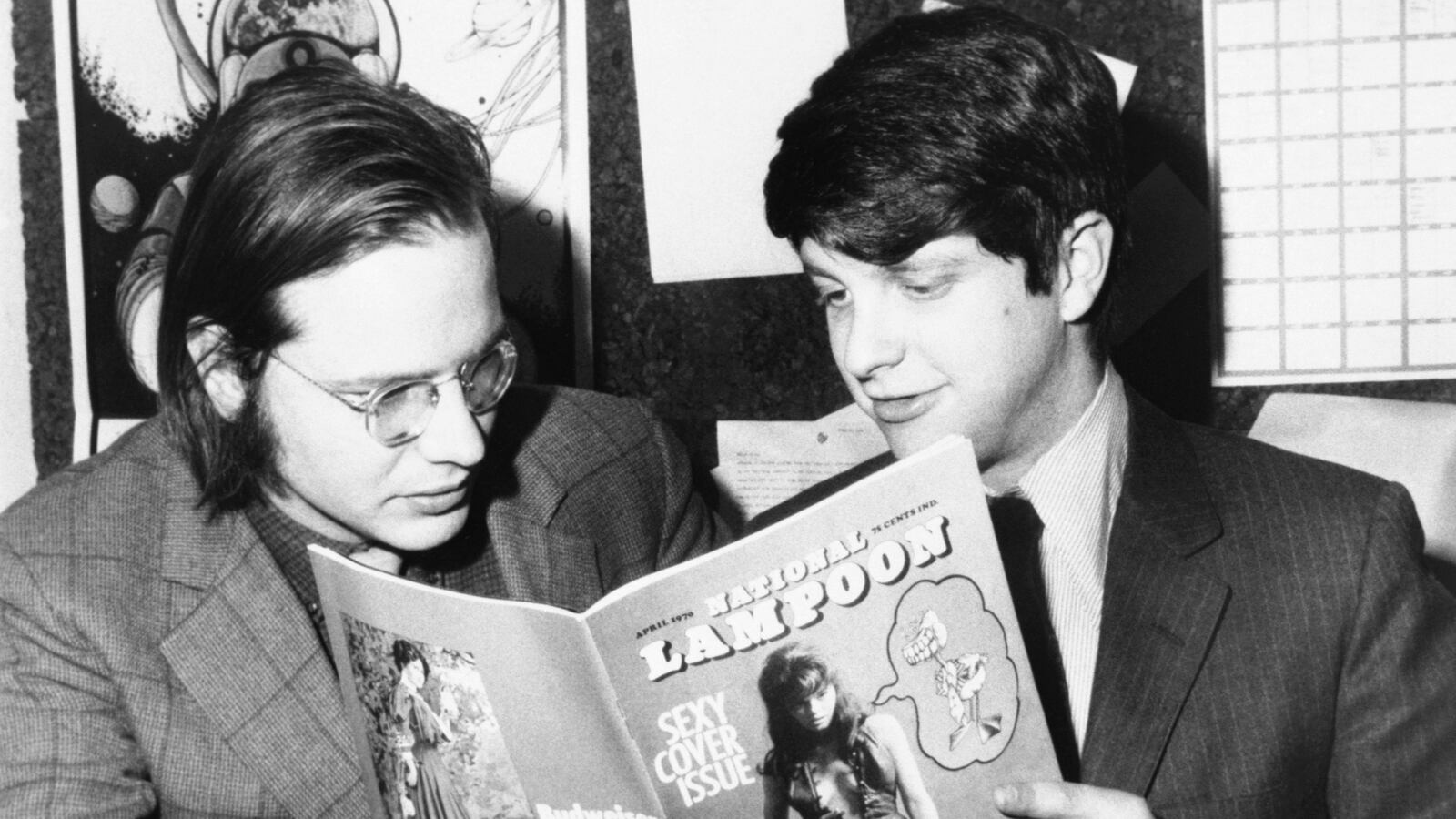

In April 1970 the first issue of the magazine they created, the National Lampoon, hit newsstands, with a cover showing a partially dressed model next to the words “Sexy Cover Issue.” In those days, people still bought magazines—for thousands of recent English majors who dream today of starting one, the history of the National Lampoon will inspire awed resentment—and though the Lampoon’s success was by no means assured, and not quite immediate, it came fairly quickly and enormously. The first issue didn’t quite sell out, but within two years, circulation was north of 500,000, and in 1974 the “Pubescence Issue” sold a million copies. The following year, the founders exercised their buyout option, for $9 million. The guys had struck it rich—and the Lampoon personality had made it big.

This idea of a magazine’s personality kept coming back to me as I read Ellin Stein’s charming and detail-rich new history of the National Lampoon, That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick, because it is not really a history at all, but a portrait. You can’t pick your offspring’s personality, and the way a personality develops on its own, involuntarily, through an array of influences of varying importance and salience, echoes the way the Lampoon personality emerges in the pages of Stein’s book—through a pastiche of eyewitness recollections, some of them contradictory, many of them fascinating, and all accompanied by the author’s breezy running commentary on the cultural storms that swirled in the background. She isn’t afraid to turn huge swaths of her book over to lengthy tangents (for a couple of chapters it reads more like a history of Saturday Night Live), to delve into the backgrounds of people whose involvement with the magazine was essentially peripheral, or to skip long periods of chronological time—the instinct being portraiture, not analysis; personality, not history.

Stein has interviewed an astonishing number of people, evidently over the course of many years. (Some are long dead.) In her primary mode, resembling a PBS documentary—letting people talk, cutting strategically among them—she shows how the Lampoon sensibility emerged at the intersection of a series of fault lines: between old and new, establishment and counterculture, insiderism and outsiderism, elitism and egalitarianism. They were the fault lines of the times, and crucially they were also fault lines that many of the founding contributors—coming from the last Brahmin days of Harvard in the 1960s and also from its most subversive chamber: its humor magazine—embodied.

Beard and Kenney set about finding recruits, mainly from four places: The Harvard Lampoon, the undergrounds, ad agencies, and, for some reason, Canada. The result was a kind of marriage of political anarchy and dorm-room apathy. Whether you think the political order is so horrible that it needs to be destroyed, or so silly it’s not worth discussing, the comedic instinct is similar: unrestrained, boundary-pushing, kill-all, farcical, and sometimes tasteless parody. Society was seen in black and white, said Michael O’Donoghue, one of the magazine’s early formative voices, the “hippies” versus the “power brokers.” The Lampoon “could stand in the center with a sniperscope and take turns blowing the shit out of all of them.”

The bullets flew—and the jokes hit. Stein accentuates the political, but the topics in the magazine ran the gamut, as its most iconic image—the cover with a puppy and a gun, and the words “If You Don’t Buy This Magazine, We’ll Kill This Dog”—attests. Much was indeed political, like a November 1972 “Special Defeat Day Sellout-Pullout Section” that came as the Paris Peace Accords ramped up and featured a tabloid paper with the headline “DEFEAT!” But a great deal was apolitical, or in between: for the snipers who let it all loose—more than Stein lets on, I think—the funniness was all. And to her credit, she serves up a lot of fun and funny nuggets out of the Lampoon’s pages, regardless of political content—a parody of The Hite Report that discusses “the myth of the penile orgasm”; a piece imagining Baptists’ hell, where demons order the sufferers to “Neck! Neck! Or I’ll make you pet!”; a pseudo-racist pamphlet called Americans United to Beat the Dutch, which “warns the reader to look for telltale florid faces, beer and/or cheese breath, and chocolate under their fingernails.” Her judicious excerpting is one of the book’s best pleasures.

More interesting to Stein than the humor, though, is the matter of influence—both of and by the Lampoon. Almost immediately, the magazine started spinning off side projects, going from book parodies and magazine supplements—the high school yearbook parody from 1976 sold 1.5 million copies—to vinyl records, such as Radio Dinner and the live-recorded show Lemmings, and finally to film, with Animal House and Vacation. With these projects, many of which became legendary, the magazine’s core group of talent got reinforcements from groups such as Chicago’s Second City improv troupe, and a number of burgeoning showbiz types came into the Lampoon orbit, where they absorbed influence, emitted some their own, and spun off meteorically into the culture: John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Gilda Radner, Ivan Reitman, and Harold Ramis.

Tracing webs of influence, Stein has a habit of overly neat psycho-sociopolitical theorizing about how the culture wars and Vietnam and Nixon and Reagan might have shaped minds and produced comedy. “The ferocity directed toward both those who served and those who avoided service suggests some ambivalence on the part of the native-born Lampooners about their own noncombatant status.” Maybe so. “With the waning days of the Nixon administration, idealists who had not managed to make their lifestyle financially viable as well as alternative realized that, unless they were independently wealthy, they were going to have to drop back in.” No doubt. Sometimes she goes beyond sociopolitics, into something like metaphysics: “Uncontrollable natural eruptions such as pimples, unwanted erections, and flatulence suggested the gap between man’s immortal soul and the decaying temple in which it was housed.” Some of this is surely true—and some isn’t—but more to the point, I don’t think it explains much about the development of a comedic personality, as if the voice on the Lampoon’s pages precipitated out of saturated vapor in the air. Stein is better when she lets the participants talk and discusses them as individuals, because it’s ultimately the rich collection of singular personalities that is both the best explainer of the Lampoon’s collective personality and the most entertaining reading.

The personalities certainly aren’t lacking. At the center are Beard and Kenney, personifications of the magazine’s famous high-low mishmash—broadly, Beard high and Kenney low. “Henry would say, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to do an interview with S.J. Perelman,’ and Doug would say, ‘We gotta get a duck for a mascot,’” Michael Frith (something of an elder-statesman adviser in the magazine’s early days) recalled. Beard comes through as the steadfast father figure who, if his creative energy burned brightly, sensibly controlled the fire and kept his band of disputatious geniuses together—for a time, at least. Stein has a good eye for indelible, reminisced details: when Beard wanted to reject an idea, he wouldn’t say no; he’d puff his pipe and say “Tempting!” Kenney, by contrast, was a shape-shifter who tried on different personalities and never quite found a fit. He’d disappear suddenly for weeks at a time and turn up on Martha’s Vineyard or in Hollywood, until in 1980 he disappeared finally, over the side of a cliff in Hawaii, in circumstances that haven’t been fully explained.

From Kenney and Beard, the personalities spiral outward. There’s O’Donoghue and Tony Hendra, who clashed and who shared an inner volatility that they each spun into comedy in different ways; Sean Kelly, a Canadian academic type who broke his own record for obscurantism several times, reaching an apotheosis with a dense parody of Finnegan’s Wake. (This would have appeared alongside pieces with titles such as “First Blowjob.”) And on and on: George W.S. Trow, Rick Meyerowitz, Brian McConnachie, Chris Miller, P.J. O’Rourke, Anne Beatts, Bruce McCall, Gerry Sussman, Ellis Weiner, Jeff Greenfield, John Hughes, and many more contributors—all come through in sharply drawn cabinet-size portraits (although, in at least one case, major aspects of biography are omitted). The heart of the National Lampoon was this constellation of individuals, and Stein’s book is at its best when it lets them shine.

But the question of influence lingers: if the National Lampoon transformed American culture, as is by now a commonplace—then how? It was not, I think, just the proliferation of side projects in other media that ultimately eclipsed the original; not merely, as Peter Kaminksy put it, that “Saturday Night Live was just like the National Lampoon except it was on TV.” Nor was it just those sociopolitical forces Stein is fond of tracing—that they were ripe to create, then absorb, this particular phenomenon. Nor was it simply the coincidental assemblage of a collection of geniuses and near geniuses who happened to find each other in the right place at the right time and start cracking jokes—not fully, anyway.

Instead the Lampoon’s enormous influence seems to me bound up with its being a magazine, and not something else: not an improv troupe, not a production company, not a TV show. Only a magazine could have focused the force of all the immensely vivid and varied personalities and served as a springboard for them to radiate outward so pervasively. Only in a magazine’s printed pages—with all those outward ticks of voice and style and layout and features—could a collective personality inhere, evolve, and reverberate so lastingly. And only a magazine, importantly, forced the sensibility to define itself and to inhere in printed words, in prose. I’m not sure it is possible for a singular comedic sensibility to develop in quite the same way—so fully as to become hugely influential—in the Web videos and tweets that now proliferate in the comedy world.

I wonder if this personality-forming potential of magazines, as a medium, isn’t an overlooked benefit in the debate about whether we need them. The notion of personality goes beyond “content” and “aggregation” and “pay walls” and even its corporatese synonym “brand”—and doesn’t seem to get much attention. Maybe it’s because the new magazines that work—the online ones—are, when done right, imbued with as much personality as the old print ones. What makes magazines special might well be something that is not inherent in the paper they’re printed on. We’ll see.

The National Lampoon, as magazines often do, declined and fell. The glory years ended, by most accounts, in 1975, but the magazine plodded on for a while. First it groped through new iterations, as sales slipped and successive generations of staffers and editors in chief tried to reinvent the collective personality with demographic research as their guide. But you can’t force a change of personality and certainly not by research-driven committee. The painful end, drawn out in time, Stein confines mercifully to a few paragraphs. In 1989 the company was taken over, and though it printed the magazine sporadically until 1998, it evolved into a mere shell, a name only, one that was lent out occasionally to bad movies.

But the National Lampoon—the personality—didn’t die. Far from it. Talk to any professional comedian or comedy writer today who was old enough to read in 1970, and he or she will reminisce fondly about those old issues, and the laughs, and the inspiration, and the enormous influence of those writers—the ones who changed everything. They might even have the old issues in a shoebox somewhere—but they certainly have that personality kicking around in their brains.