It’s comforting to meet another writer who is as frustrated as I am with living in the Digital Age where nothing works. I always thought printing up T-shirts that read, “Nothing Works,” would sell like hotcakes, until I realized that Millennials would have no idea what the T-shirts were referring to.

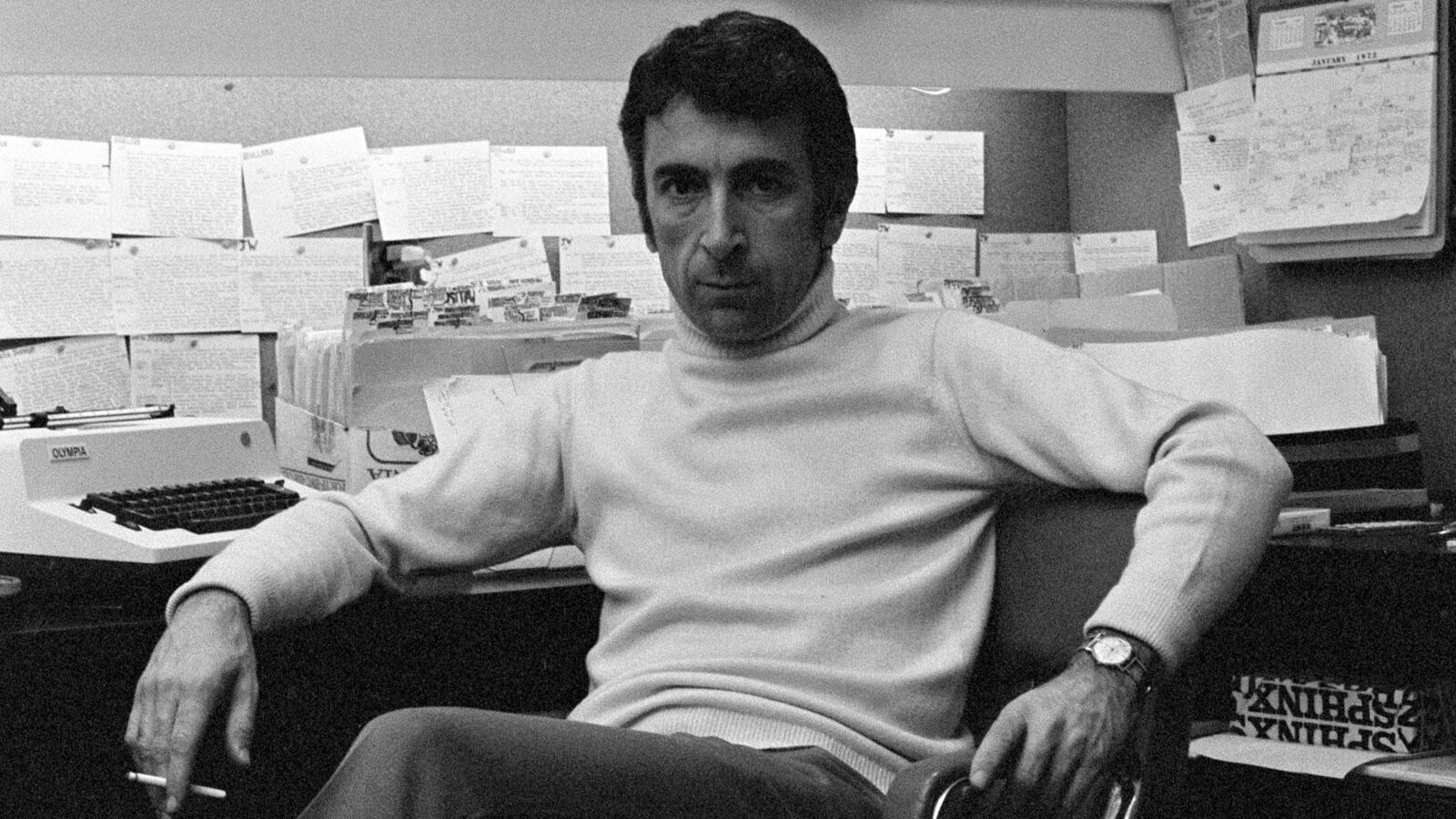

Thank God, Gay Talese, at 91 years old, perhaps the world’s oldest living bestselling author with 17 books to his credit, and a new one just out— Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener (Mariner Books)—knew exactly what I was talking about.

“I haven’t changed,” Talese told me over the phone before his publisher or publicists had time to return my emails; he just called my cellphone 10 minutes after I emailed my request for an interview.

“The world has changed in wonderful ways, but not me,” Talese confessed as I struggled to set up my phone taping equipment. “I don’t know if I changed the world at all, but I still get my work done in my archaic way of doing things. I don’t know how else to do things, because I never mastered the new technology, nor have I never been interested in mastering the new technology. I’m not sure if I should be proud that. As a retro person, I don’t know why I should be proud of it, but I have to be truthful…”

Of course, Gay Talese changed the world. His most famous achievement, according to celebrated author Tom Wolfe, was the invention of “New Journalism,” that inspired such writers and reporters as Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Hunter Thompson, Joan Didion, Jean Stein, George Plimpton, Terry Southern, Mark Jacobson, Michael Daly, Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, as well as Wolfe himself. To put it simply, “New Journalism” was a literary movement in the 1960s and ’70s that combined fictional techniques and styling with fact-based reporting.

But Talese refused to take credit as the “inventor” of “New Journalism.”

“I didn’t know what the hell ‘New Journalism’ was,” Talese explained, “First of all, I didn’t want to be named the founder of anything. All I wanted to do was, instead of writing fiction, I wanted to write in a realistic way, because I didn’t want to make it up. I used to read short stories in The New Yorker by John Cheever, or John O’Hara or Erwin Shaw, and they were wonderful writers. And I wanted to write like those guys in The New Yorker, who were writing fiction, but I wanted to write non-fiction in the same style.”

Perhaps Talese’s most famous moment in “New Journalism” came when Esquire Editor Harold Hayes assigned him to write an article on Frank Sinatra, and like his famous alter-ego, Bartleby, from Herman Melville’s 1853 short story, Bartleby, the Scrivener, Talese told Harold Hayes, “I prefer not to.”

“I did prefer not to, in a very vociferous way,” Talese chuckled as he recalled the altercation with his editor over the Sinatra article. “But my editor at that time was Harold Hayes, a great editor but a real tough guy. He was a hard-nosed ex-Marine, and he wasn’t going to take no for an answer from me. Harold Hayes came from North Carolina, and his father was a Methodist minister, so he had a sense of virtue, and a sense of vigorousness, and a sense of command, because he was a fucking Marine officer in the Korean War. And I worked very well under him, but never happily, because he was always a terrifying figure.”

“But I didn’t want to write about this guy, Frank Sinatra,” Talese continues, “I didn’t want to do it, and I said, ‘Jesus Christ, everybody’s done Frank Sinatra! Everybody! The only thing you can say about Frank Sinatra is it’s all been written before! It’s already appeared!’

“Harold went, ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be easy.’”

Gay Talese, Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal at Peter Max after a performance of “Don Juan in Hell.”

Richard Corkery/NY Daily News via Getty ImagesTalese took the job. “I flew out there to L.A. and Sinatra had a cold, but Walter Cronkite apparently screwed Sinatra in a taped interview for a CBS show, when producer Don Hewitt had Cronkite ask Frank about the Mafia and Organized Crime, and Sinatra went ballistic on him.

“I read that in the newspaper after I got on the plane, and I thought, ‘Oh, shit! Sinatra’s not going to like talking to me. He’s pissed off at the press!’

“Sinatra’s lawyers were going to sue Cronkite, so I didn’t know what to do,” Talese admitted, “But I had friends, a married couple named Jack and Sally Hanson, whom I knew from previous trips to California, and they owned a club called The Daisy, a discotheque. It was a supper club. I was staying at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, and I called Jack and Sally, and they said, ‘Come over, have dinner with us.’ So that night I went to The Daisy, and I saw Sinatra at the bar, he was sitting with two blondes, and I thought, ‘I better not talk to him. He’s going to be pissed off at the press!’”

What everyone fails to mention about this unexpected encounter in 1965 between Talese, the “Father of New Journalism,” and Sinatra, leader of the “Rat Pack,” was that a new generation was emerging out from under the old one, forcing UPI reporter Vernon Scott to claim, “The Daisy is possibly the first institution to bring together Hollywood’s old guard and the young, hip set.”

The Daisy did as much to ignite the “Sexual Revolution” in America as the film Deep Throat, and The Pill.

“[Jack Hanson] used to wonder why women weren’t more attractive,” Dan Jenkins profiled the Hansons in a 1967 issue of Sports Illustrated. “They didn’t dress right, he decided. This was in the early 1940s, when women looked either like Joan Crawford with broad shoulders out to here, or like Charlie Chaplin with baggy slacks.”

That’s when “Jax” pants were born, those tight-fitting precursors to today’s impossibly snug blue jeans, and exclusive “Jax” stores sprung up in Beverly Hills, but it was his wife, Sally Hanson, who corrected Jack’s idea of the way women should look.

“One of the girls who hung around the windows most often was Sally.” Dan Jenkins explained, “Like Hanson, she had come out of Hollywood High, but a few years later, and she also thought she knew something about clothes; at least, she knew what she liked to wear. She liked to wear Jax pants, and she convinced Hanson that she could design them better than he. He hired her, and they built the business together. After seven years they got married. Sally is still the designer, but Hanson takes a hard look at every new item to make sure it is jazzy enough.”

As Dan Jenkins described The Daisy, “It is a place where this great montage of thigh-high miniskirts and glued-on Jax pants are doing the skate, the dog, the stroll, the swim, the jerk, the bump, the monkey, the fish, the duck, the hiker, the Watusi, the gun, the slop, the slip, the sway, the sally and the joint. Like all good Beverly Hills children, Daisy dancers never even sweat.”

With all that money Jax pants brought in, it was time for a Beverly Hills mansion, a Rolls-Royce and even a nightclub called “The Daisy,” after the burgeoning “flower power movement” that had just been planted.

Yes, The Daisy, with its sexually liberated celebrity cliental, was the perfect place for Talese to witness the first cracks in the rupture that would soon become known as “The Generation Gap,” that would soon divide the country for the rest of the decade.

Gay Talese attends Esquire 80th Anniversary And Esquire Network Launch on September 17, 2013 in New York City.

Dimitrios Kambouris/WireImage/Getty ImagesIt seemed Sinatra was taking offense to all these kids at The Daisy, smoking pot and wearing far-out clothes, and listening to that horrible rock ’n’ roll music.

As Talese wrote in, “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold,” “Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel—only worse. For the common cold robs Sinatra of that uninsurable jewel, his voice, cutting into the core of his confidence, and it affects not only his own psyche but also seems to cause a kind of psychosomatic nasal drip within dozens of people who work for him, drink with him, love him, depend on him for their own welfare and stability. A Sinatra with a cold can, in a small way, send vibrations through the entertainment industry and beyond as surely as a president of the United States, suddenly sick, can shake the national economy.”

Sinatra soon set his sights on sci-fi writer Harlan Ellison, who was wearing, “a pair of soft deerstalker boots, like Robin Hood, they come up and fold over,” Ellison explained on a YouTube video. “Really handsome soft brown leather, and a pair of loden green corduroy pants tucked into them, and a suede top with thongs. So I was kind of a Captain Blood-looking guy, but I’m five foot five, I weighed about 120 pounds…”

Frank Sinatra was in one of those drunk, pissy moods, his cold making him even more insufferable as he watched Leo Durocher and Ellison shooting pool. Ellison looked Robin Hood in brown corduroy slacks, a green shaggy-dog Shetland sweater and suede-fringed boots.

It was Ellison’s boots that Sinatra targeted.

“Finally,” Talese wrote in Esquire, “Sinatra could not contain himself.

“‘Hey,’ he yelled in his slightly harsh voice that still had a soft, sharp edge. ‘Those Italian boots?’

“‘No,’ Ellison said.

“‘Spanish?”

“‘No.’

“‘Are they English boots?"

“‘Look, I donno, man,’ Ellison shot back, frowning at Sinatra, then turning away again

“‘Now there was some rumbling in the room, and somebody said, ‘Com’on, Harlan, let’s get out of here,’ and Leo Durocher made his pool shot and said, ‘Yeah, com’on.’ But Ellison stood his ground.

“Sinatra said, ‘What do you do?’

“‘I’m a plumber,’ Ellison said.

“‘No, no, he’s not,’ another young man quickly yelled from across the table. ‘He wrote The Oscar.

“‘Oh, yeah,’ Sinatra said, ‘Well I’ve seen it, and it’s a piece of crap.’

“‘That’s strange,’ Ellison said, ‘because they haven’t even released it yet.’

“‘Well, I’ve seen it,’ Sinatra repeated, ‘and it’s a piece of crap.’

“‘Hate to shake you up,’ Ellison said, ‘but I dress to suit myself.’”

It wasn’t the first time Frank Sinatra acted like an asshole. Around the same time, Sinatra had paid George, the maître d’ of the Daisy, to punch columnist Dominick Dunne in the face, while Frank, who was with Mia Farrow, watched smugly from the sidelines.

The newspapers were filled with mentions of Sinatra getting into fisticuffs with photographers, reporters, and onlookers throughout his career, but that night at the Daisy with Ellison was different, because Talese was in attendance, and he carried with him a secret weapon.

“You remember those shirt cardboards?” Talese asked me over the phone, “You know what I’m talking about, shirt boards? They were 14x8 inches stiff cardboard, that came with a shirt. Most people throw it away, but I cut them up in five sections. And I rounded off the edges, so it fits in my pocket.

“If I’ve got two or three shirt boards,” Talese continued, “I have about 15 pieces of a 7x3 inches cardboard sheets that I used to make notes. I don’t make big, long notes. They’re just reminders. And every night when I’m on assignment I get a typewriter, I type out my notes for the day. I’ll say you know, ‘August 29, at 4:40, talked to Legs McNeil on the phone. Then the dog came in and pooped on the floor, I had to clean it up. I’m talking to Legs McNeil, and then Mary came in and says, “Somebody’s downstairs from the tax department, they want to know why you didn’t pay your income tax last year.”’”

“Truman Capote thought he had total recall,” Talese chuckled again, “But I don’t have total recall, but I recall pretty well, and then I go over it later with the person I’m interviewing. I called Harlan Ellison the next day, confirmed that I heard what I heard as to the confrontation, and Harlan added a few things.”

As the late Harlan Ellison later verified on a YouTube video, “I told him what happened and Talese says, ‘Yeah, that’s what happened,’ I said, ‘But how do you know I’m telling the truth?’ And he said, ‘Because I was there.’ Whaaaat?”

Cut-up shirt carboards is why Gay Talese can write such extraordinary paragraphs, like this one that concludes “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold”:

“It was the morning after. It was the beginning of another nervous day for Sinatra’s press agent, Jim Mahoney. Mahoney had a headache, and he was worried but not over the Sinatra-Ellison incident of the night before. At the time Mahoney had been with his wife at a table in the other room, and possibly he had not even been aware of the little drama. The whole thing had lasted only about three minutes. And three minutes after it was over, Frank Sinatra had probably forgotten about it for the rest of his life—as Ellison will probably remember it for the rest of his life: he had had, as hundreds of others before him, at an unexpected moment between darkness and dawn, a scene with Sinatra.”

As Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener is released on Sept. 19, 2023, Gay Talese continues to work on his long-awaited account of his 64-year marriage to Nan Talese, titled, A Non-Fiction Marriage.

“I’m doing that now,” Talese explained, “You know, many times in those 64 years, I thought I was barely married. We had an on-again, off-again, on-again, off-again marriage. You know in 64 years, it’s not a honeymoon, believe me.”

Writer Gay and Nan Talese at a party for Halston at Bloomingdale’s.

Photo by Fairchild Archive/Penske Media via Getty ImagesI laughed, and had to ask, “So what do you factors do you contribute to having such a long marriage?”

“The great thing was that Nan always had a job, which saved the marriage,” Talese confided, “My wife, from the time we got married, until recently when she turned 87, she retired, but she always had a job. She’s 89 now.”

“Was she upset with you when you published Thy Neighbor’s Wife in 1981?” I asked. For the initiated, Thy Neighbor’s Wife was a participatory chronology of America’s sexual revolution that turned Bettie Page into a fashion icon—and caused Gay and Nan to separate.

“Nan hated Thy Neighbor’s Wife,” Talese confessed, “We separated, but it wasn’t long. We did a couple separations. You know, I was on that book for about six years. I started the book in 1972, I didn’t finish it until 1979. During that time, I certainly spent time with a lot of other people and one of them was Sally Hanson, who divorced Jack Hanson, and she was the girlfriend of mine I took with me to Sandstone, which is a nudist colony in Topanga Canyon, overlooking Malibu and Los Angeles. My wife wouldn't go with me to Sandstone, so I took Sally Hanson, who went very happily. So she was like, my surrogate wife for a while.”

“How did you reconcile with Nan after Thy Neighbor’s Wife?” I asked.

“Well, you know, I never fell in love with anybody else,” Talese stated matter of factly, “And I tell you, the most important thing, and I don’t want to sound philosophical, but one of the things about my life with Nan, my wife, is even when I was angry, she was angry, I never lost respect for her. I never lost respect. Even when I was falling out, I never lost respect. And she didn’t, I don't think she lost respect for me. I think the most important thing in keeping a marriage together is having, maintaining respect for one another. If you have respect, you have something to work with.”

“And also, the second thing that was most important, we always had two bathrooms,” Talese was deadly serious. “You can’t have a marriage that lasts with one bathroom. That’s essential, two bathrooms. The most important thing is not the sex because sex doesn’t make a fucking bit of difference in marriages, but bathrooms matter.”