One morning soon, Dr. Derric Nimmo will head into the mangroves of the Florida Keys with a two-liter box of 1000 live genetically modified Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. He will shake it, remove the lid, and watch them disappear into the sky.

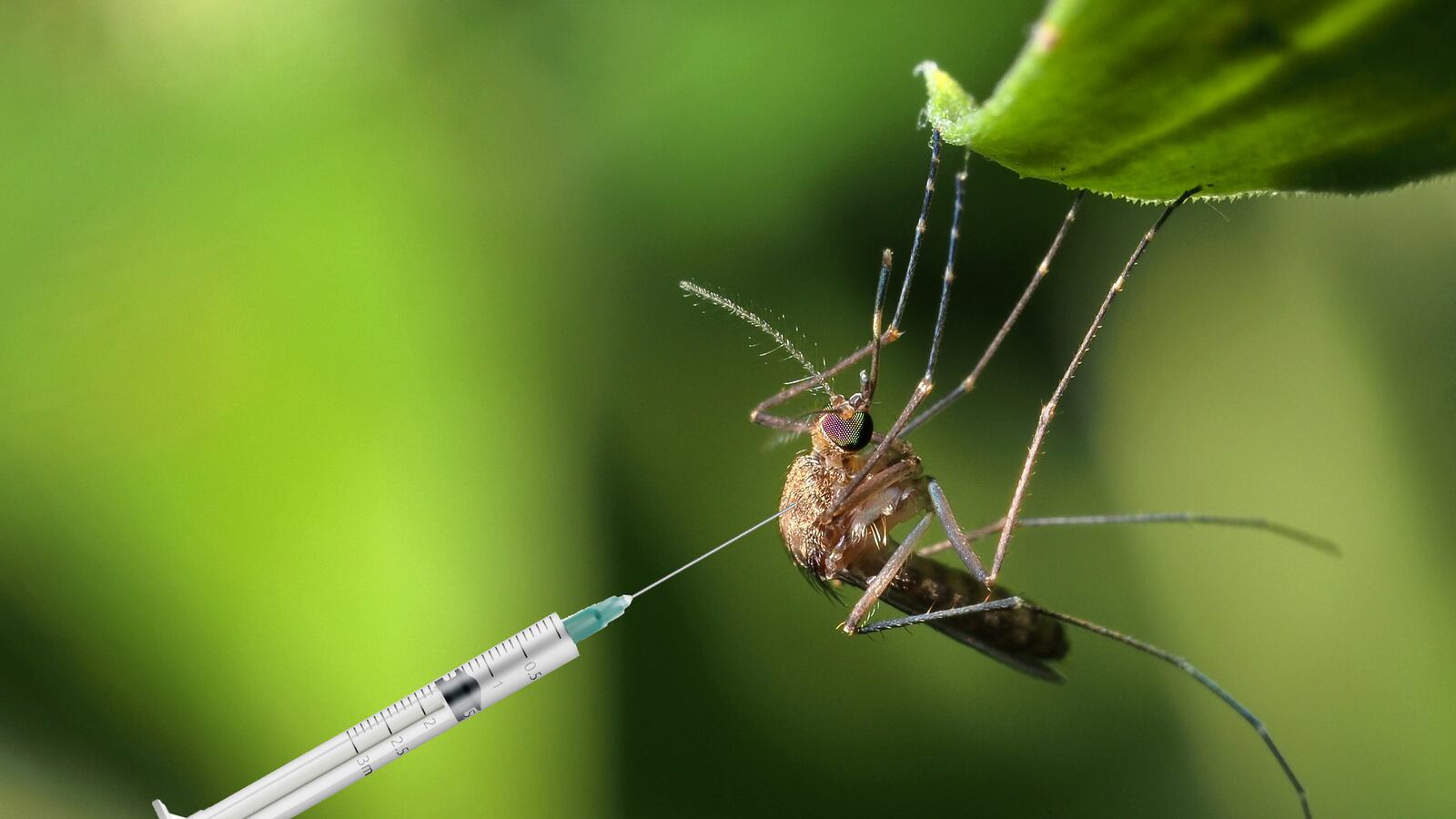

Although normal in appearance, all 1000 of them (exclusively males) will have been injected with a flawed gene that prevents their offspring from surviving to adulthood. An army of sorts, secretly equipped to destroy their own.

Eliminating—or at least drastically reducing—the number of Aedes aegypti is extremely beneficial to humans. The most dangerous mosquito on the planet, they are the prime vector for a wide range of serious and even deadly diseases including Dengue, Chikungunya, and most recently, Zika.

Although a new concept in America, for Oxitec, the British-based biotechnology company, the concept is nothing new. The technology to create these lethal mosquitoes has been around for years—and has proven successful. Part of this is due to the one-track mind of the male mosquito. “They’ve got one job after [being released]: find a female and pass on their genes,” Nimmo, Oxitec’s point person in Florida tells The Daily Beast. “Doing so causes their offspring to die.”

Over the past five years, Oxitec has conducted five trials of their GM mosquitoes in three different tropical regions (Cayman Islands, Brazil, and Panama)—all of which showed a 90 percent reduction of the Aedes aegypti population within six to nine months. In America, the idea has remained stuck in a regulatory quagmire for years. Nimmo, who was first called to Florida by government officials during the 2009-2011 dengue outbreak, has been trying to get it approved ever since.

He’s done his homework, and then some—building a facility for the creation of the mosquitoes, publishing a 285-page environmental assessment of the impact, and traveling around southern Florida talking to residents about why the program is both safe and effective. This March he got a big win when the FDA released a report that found “no significant impact” from the Oxitec mosquitoes.

In the wake of the report, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency expressed their support for the project moving forward.

Now, with a severe outbreak of Zika spreading across the world, the need for an efficient and effective mosquito solution has never more urgent. Still, Oxitec is months away from being able to use the groundbreaking technology on U.S. soil. It’s not the government that is keeping the Oxitec mosquitoes off the land—based on the FDA’s recommendation they could start tomorrow. It’s the people of southern Florida themselves who are boycotting—people who are unwilling to believe that anything modified by science is safe.

In defiance, residents of southern Florida have launched an opposition campaign that includes putting signs in their yard that read “No Consent.” One resident, Mila Demier, started a petition on Change.org requesting that Oxitec be banned from releasing the mosquitoes. “Don't let Oxitec bully our community!” she writes. “We say no to genetically modified mosquitoes in the Florida Keys!” As of Wednesday, her petition boasted more than 160,000 signatures.

As is, the fate of Oxitec’s program in the Florida Keys now sits in the hands of the residents there, who will vote on it in November. Until then, Nimmo’s hands are tied—meaning that he’s sitting on what could be the solution to a Zika outbreak that has infected tens of thousands worldwide, including 1,000 Americans. Beyond the flu-like symptoms, Zika has been linked to severe birth defects like microcephaly and nerve disorders like Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Many of the problems it causes are still unknown.

Other efforts to curb the epidemic, such as vaccines, are underway, but are years from becoming realistic solutions. Oxitec has been prepared for an epidemic of this nature for decades. The idea of the genetic mutation itself, according to Nimmo, dates back to the 1990s when Oxford researcher Dr. Luke Alphey became obsessed with finding a way to mimic sterile insect techniques in mosquitoes. Creating sterile male insects had proven successful in eliminating entire species, most famously the screwworm.

But in mosquitoes, a much more threatening creature, sterilization made them too sick to be functional. Instead Alphey started working a specific gene that would keep the mosquitoes from getting sick, but still lead to their demise. Along with another Oxford researcher named Dean Thomas he formed the organization Oxitec (Oxford Insect Technologies) in 2002 to dedicate his time to finding the solution.

Fast forward more than a decade and Oxitec, which was recently acquired by the American company Intrexon, is a hotbed for innovation on the biological level. In a recent Ted talk, the company’s CEO Haydn Parry discussed the importance of the project. “What we're actually doing is taking the mosquito and giving it the biggest disadvantage it can possibly have, rendering it unable to reproduce effectively,” said Parry. “So for the mosquito, it's a dead end.”

Parry echoed Nimmo’s mention of the importance of male mosquitoes finding females to mate with—a job that he says have more or less mastered. “Males are very, very good at finding females,” he said on the Ted stage. “If there's a male mosquito that you release, and if there's a female around, that male will find the female.”

He went on to explain why it’s superior to pesticides (more accurate and targeted) and how 150 million Oxitec mosquitoes had been released to date without a single human harmed in the process. On top of the CDC and EPA offering their support, he verified that the World Health Organization has also endorsed the project. The process has been so successful in Brazil, one of the first places which Oxitec tested the procedure, that the government there has asked them to expand to a region of 300,000 people. Nimmo says they were asked about Rio de Janeiro, but it was too late to be effective.

If these endorsements aren’t enough for southern Floridians, the FDA impact statement should be.

In it, officials address two of the main concerns—one, that people bitten by female mosquitoes would be exposed to the protein from the male gene, which it deemed “highly unlikely.” The other, that reducing the number of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes could have some adverse impact on the environment—concerns which the FDA concluded were “largely negligible.”

The agency opened the document up to public comments for 60 days after posting it in March, but have yet to receive any evidence that’s changed their mind. The 285-page report Nimmo helped draft contains over 150 publications of the research they have conducted, which is all independent and peer reviewed. Beyond the backing of the science world, a Purdue study from February found that 78 percent of Americans support the introduction of GM mosquitoes.

So why, faced with a potentially life-changing solution that both the science world and general population support, are southern Floridians so opposed?

“The main arguments are the unknown and you can’t predict them,” says Nimmo, who has spent countless hours fielding questions in town halls, on radio shows, and in his office. “That’s why you do trials and we’ve done trials, we’ve done them for six years. This isn’t a new technology, it’s not like that at all.”

Nimmo says some of the residents have gone so far as to craft conspiracy theories that revolve around the idea that Oxitec actually launched the Zika epidemic. “I get frustrated,” Nimmo says. Considering that the male mosquitoes cannot bite (they don’t have the mouthparts) and that Oxitec’s method for sorting the genders is 99 percent accurate, this theory is far-fetched.

But despite a plethora of facts proving this—and the idea that these mosquitoes could wreak havoc on the earth—wrong, many stubbornly assert that the GM mosquitoes are dangerous.

Dr. Nina Fedoroff, who wrote an op-ed in The New York Times on the topic in April, says it’s less about mosquitoes and more about genetically modified organisms in general. Federoff, who has no connection with Oxitec, wrote that their method is “our best hope for controlling the mosquito-borne Zika virus.”

But three months after she posted the article, Oxitec is no closer to getting them released. “The fact that it’s a GMO has everybody on edge,” she says. She hypothesizes that much of this “fear” stems from the Organic food industry, which has “vilified GMOs for profit.” As the GM mosquitoes prove, she says, not all genetically modified things are bad.

“You ask most people about GMOs and they say ‘I don’t know what they are but I know they’re bad’ Well how do they know?” Federoff says. “You don’t see a whole lot of positive.” Fedoroff is hoping that Oxitec—a group of scientists she’s long been a “big fan of,” will interrupt this narrative.

“This lethal strain is like insecticide without the downsides of insecticides,” she says, citing the fact that mosquitoes can develop resistance to insecticides and that it can be toxic to other beneficial insects. “This is the smartest thing that I have seen to address the vector situation,” she adds, “it’s about as good a self-limiting design as you could possibly have.”

Whether or not the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have a future in southern Florida is now up to the residents to decide. Until they do, Zika rages on.