George Chakiris loves the question, “What was it like?”

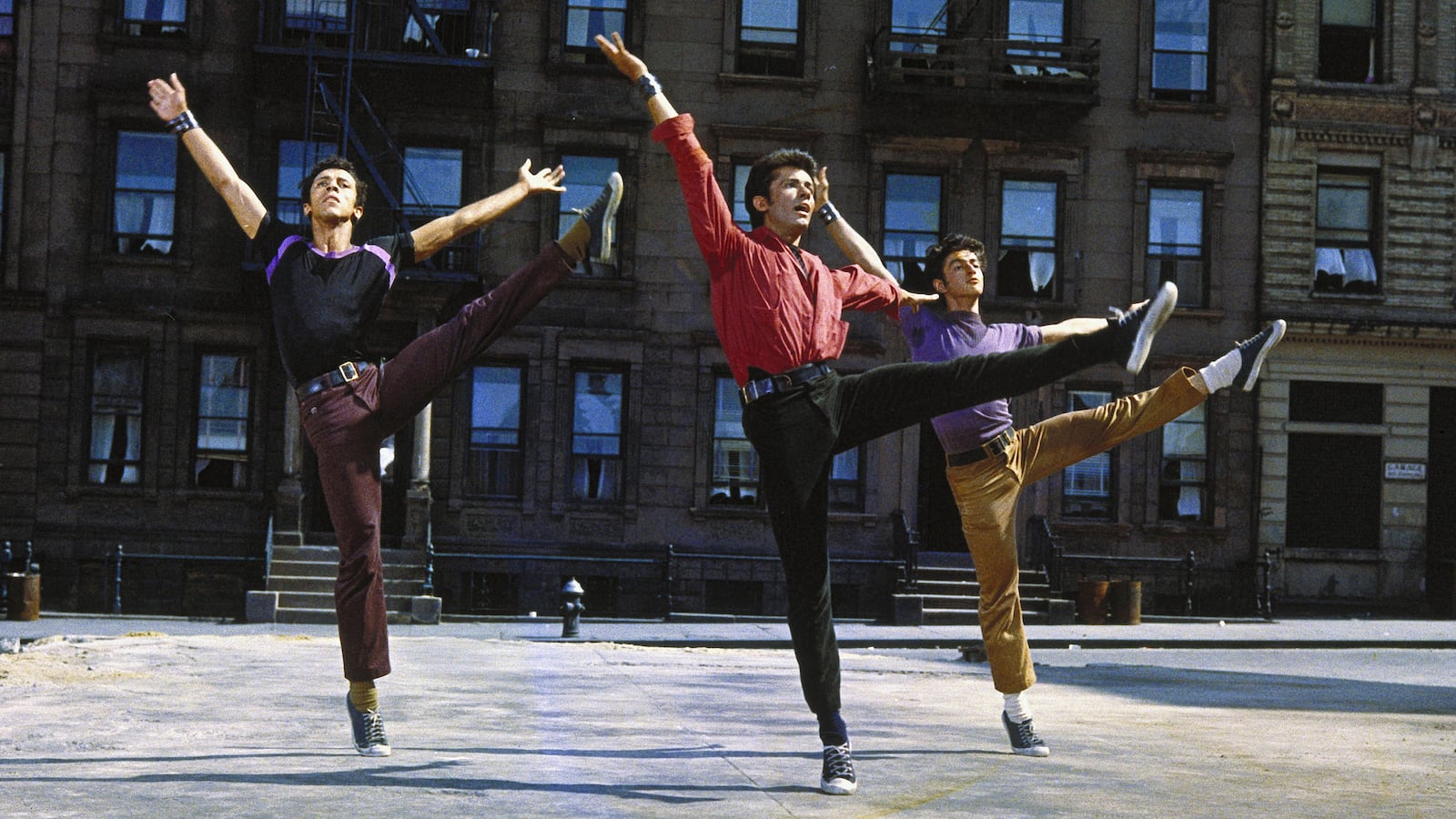

What was it like to film West Side Story? What was it like to win an Oscar for his performance as Bernardo?

What was it like to work with legendary choreographer and director Jerome Robbins? What was it like to be a dancer in the Golden of Age of Hollywood?

What was it like to be in the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number with Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes?

West Side Story is celebrating its 60th anniversary this fall. It’s a milestone that has garnered renewed interest in the original film thanks to a recent Broadway revival and a remake of the film set for release later this year from Steven Spielberg. Suffice it to say, the 86-year-old actor has been answering the question a lot.

He’s participating in a cast reunion alongside Russ Tamblyn, who played Riff, and Rita Moreno, his screen partner and the iconic Anita, that premieres Thursday night as part of the TCM Classic Film Festival on TCM and HBO Max. He recently published a memoir, My West Side Story: A Memoir, about that time in his career. Especially with the recent trailer for Spielberg’s West Side Story eliciting nationwide goosebumps, people are asking more than ever, “What was it like?” Gifted the opportunity to look back, he’s taking delight in remembering himself.

“I think I have the same fascination and interest,” Chakiris tells The Daily Beast in a recent interview. When he’s had the opportunity to work with someone who has a connection to the romanticized Hollywood of yore, it’s a reflex for him, too, to ask the question.

George Chakiris poses with his book next to his handprints during the ceremony unveiling the new plaque honoring all the 100+ Oscar winners who got their handprint-footprints at the TCL Chinese Theater, April 21, 2021, in Hollywood, California.

Valerie Macon/AFP/GettyMore than anything, he’s tickled that people have that same instinct when it comes to him. “It’s nice to revisit all the nice things that happened in my life, and the wonderful people I got to know and work with,” he says. “I’ve loved being able to revisit all the good things.”

Chakiris was born in Ohio, the son of Greek immigrants and one of six siblings. Early memories involve dancing with his sister in their family home. When the brood moved to California, he began taking dance classes, grateful for a lack of judgment on behalf of his parents when their son wanted to study ballet in the 1940s.

After dropping out of college and moving to Hollywood, he worked a desk job at a department store and took dance classes at night. He eventually landed roles as a chorus boy singing and dancing in a slew of ’50s musicals: Stars and Stripes Forever, Call Me Madam, White Christmas, Brigadoon, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Spot him lithe and dapper dancing behind Marilyn Monroe while she, in her hip-hugging pink dress and solar-flare charisma, makes cinematic history performing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.”

“One of my favorite credits, to use that word, is being able to say that I was one of the guys behind Marilyn Monroe in that number,” he says. “I love being able to say that because everybody remembers that and loves Marilyn Monroe.”

His big break came courtesy of a publicity photo. He was hired as a dancer for White Christmas, but marketing materials featuring him next to star Rosemary Clooney started to earn him fan mail at Paramount, which then signed him to a studio contract.

“It feels so good to have been part of all that in whatever way I was,” he says. “I was just a chorus dancer, but I loved being a chorus dancer. I danced behind Rosemary Clooney and Marilyn Monroe and so on. Those were great days.”

For all the storytelling about his time on West Side Story over the decades, there are still surprising things to learn. For example, the Oscar-winning Bernardo had previously played Riff in the stage musical that preceded the movie.

Disillusioned with his Hollywood career, Chakiris moved to New York, where he auditioned for legendary choreographer Jerome Robbins. Robbins cast him as the leader of the Jets, sending Chakiris to London, where he earned rave reviews for his West End performance as Riff—and would pal around with Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney, and Julie Andrews in his free time.

When word spread that a film version of the musical was in the works, the stage cast assumed they would be passed over for movie stars. But sure enough, Chakiris was offered a screen test, though he was surprised to be asked to read for Riff and Bernardo, the Puerto Rican leader of the Sharks. (Chakiris, again, is of Greek heritage.) After Natalie Wood was cast as Maria, Chakiris, because of his swarthy complexion, was thought a better fit for Bernardo than Riff.

“You know, it’s funny how picky you can get as a young person and be like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to play that, I don’t want to play this…’” Chakiris says. “Because I was playing Riff in the theater every night, that was what I knew. And so I was hoping that I would be cast as Riff.”

Still, he admits with a chuckle, being cast as Bernardo worked out pretty well for him. He won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his work and, because the film version incorporated Bernardo and the Sharks into its tour de force “America” number alongside Anita and the girls, he is part of what may be the greatest musical scene in film history.

“In the theater version of the show, the song ‘Cool’ is sung by Riff, so the role of Riff has more meat on the bone, so to speak,” Chakiris says. “In the film version, because the guys are included in ‘America,’ Bernardo has more meat on the bone. So I kind of had the best of both worlds playing Riff in the theater and playing Bernardo in the film.”

When production wrapped on the film version of West Side Story, by the way, he went right back to playing Riff on stage.

In talking about West Side Story over the years, there are oft-repeated stories that he likes having the opportunity to correct.

First among them is the increasingly, he says, exaggerated report that Robbins, whose choreography for the show changed the way dance is used in musical-theater storytelling, was too domineering and caustic to endure.

“A lot of the dancers hated him but loved him,” Moreno once said about working with Robbins on the “America” sequence. “He would think nothing of making us do one step over and over until we broke down in tears or pulled something. Shin splints for days. He was a tough and demanding daddy, but if you got a smile out of him, you floated on air for days.”

West Side Story lyricist Stephen Sondheim has said, “He’s the only genius I’ve ever met, but he was demanding and easily offended. You came out scarred, but you came out with good work.”

Chakiris speaks highly and defensively about Robbins.

“Jerry has a tough reputation, which I’m sure he’s earned,” he says. “But there is the other side of Jerry that people don’t stop to consider when they talk about him. There’s this almost cliche kind of reputation that he has about being difficult and all that, and he could be. But he was a perfectionist, and he was a perfectionist with himself first.”

“It was hard, I think, to be him, and to be the artist that he was, because he couldn’t settle for anything less than the best, and that’s hard,” he continues. “He was hard on himself because of that. But that’s what makes him tick, and that’s how he achieved what he achieved.”

The years have also brought a deserved reconsideration about the way the Puerto Rican population is portrayed in the film.

In a recent interview with The Daily Beast, Moreno spoke about how she nearly quit the movie when she realized how denigrating some of the lyrics in “America” were to Puerto Ricans. (Of the film’s leads, she was the only one actually of Puerto Rican descent.) The lyric was eventually changed.

Spielberg’s version of the film, which works off a screenplay adaptation from Tony Kushner, “corrected many, many of the wrongs, if not all of them,” she said. “Steven and Tony Kushner really worked their asses off to get it right.”

Both Moreno when we spoke then and Chakiris now are careful to point out that while evolutions and updates to the story’s racial politics are to be celebrated, that shouldn’t be at the expense of acknowledging, for its flaws, how bold and, in large part, unimpeachable their film still is.

“Steven Spielberg has the blessing, so to speak, of being able to look at something that exists and thinking how he might do this or that to change things,” Chakiris says. “But that’s not the same as creating something.”

The years have also given Chakiris the opportunity to reflect on what, from today’s perspective and after much-needed discourse about representation, diversity, and inclusion, would never happen—at least not without controversy. The fact that Moreno is the only Puerto Rican lead cast member is somewhat shocking from a modern point of view.

“I totally understand and get the conversation that’s going on today,” Chakiris says. “If somebody’s going to play Puerto Rican, it would be nice if they were actually Puerto Rican. But to me, the most important thing in casting is, putting ethnicity aside, you need to have the freedom to hire the person—not the background, but the person—who is best suited to play the role the way you envision it as a producer or a director.”

He stresses how important that conversation is today, and how vital the practice of representational casting is. But it’s also a very different time in the industry than it was 60 years ago.

“Thinking back, if that had been the national or worldwide conversation at the time, that would have been taken into consideration,” he says. “But that wasn’t what was going on in the United States and in the world. People were free to cast without being quote-unquote ‘politically correct.’ I think it’s good to be politically correct, especially now. Because we have so many more people in the business now, you have so many more people to select from. So it’s really possible to be politically and artistically correct at the same time.”

On the topic of casting white actors to play Puerto Ricans, he would also like to correct something his good friend and co-star Moreno has said in the past.

As she told the Beast, she was mortified while in the makeup chair about how much dark foundation and tinted paint was being put on her and her co-stars to make them read more ethnic on screen. “Poor George Chakiris always looked like he had been dipped in a bucket of mud,” she said.

Chakiris swears the makeup never looked wrong to him, and felt it was correct for the project they were all doing. He brings up that Moreno has also said in the past that Puerto Rican people can have a range of skin tones.

“In her saying that, that means that any shade in between is acceptable because she’s saying that all those colors, all those shades apply,” he says. “So the makeup never occurred to me because I wasn’t wearing heavy makeup. I wasn’t! I would like to stop that rumor from going on because it isn’t the truth.”

When asked if revisiting all those stories—and clarifying all those rumors—ever leads to rewatches of the film, Chakiris has a surprising answer. He estimates the last time he watched it was a decade ago at a 50th anniversary celebration at Los Angeles’ Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Before that was likely at the 40th anniversary soiree at Radio City Music Hall.

He only ever wants to see it on a big screen. “So I’ve only seen it, believe it or not, maybe five or six times in all these 60 years.”

“At the beginning, I think, well, I don’t think I’ll sit through all this,” he says. “But I end up sitting through the whole thing because it grabs me like it grabs anybody. Once it’s started, I can’t leave the theater. I love following it to the end and that beautiful last scene which is so, so moving. As much now as it was then.”