When conservative commentator and Wisconsin GOP kingmaker Charlie Sykes put a little-known businessman on the map in 2010, Sykes thought he knew who he was turning into a Republican Party star.

According to Sykes, this great hope for the GOP was a “solid, Midwestern, Wall Street Journal editorial page Republican.”

His name was Ron Johnson. And in Sykes’ telling now, it would’ve been near-impossible to imagine the politician that Johnson became.

To some extent, Johnson is still a walking Wall Street Journal editorial page. On Monday, he wrote in those pages that he will seek a third term representing Wisconsin in the U.S. Senate.

In true RonJon form—as he’s colloquially referred to on Capitol Hill—Johnson initially vowed to serve only two terms. But staring at his self-imposed pink slip, Johnson declared that “America is in peril,” forcing him to seek another term in power to fight “the Democrats’ complete takeover of government and the disastrous policies they have already inflicted on America and the world.”

The announcement instantly put Johnson at the top of Democrats’ 2022 target list and set up a marquee Senate battle in the Badger State, one of the most starkly divided in the country.

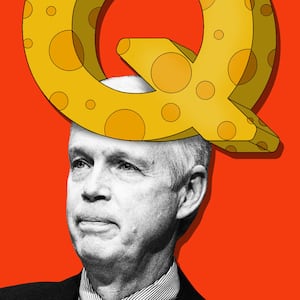

But, in the eyes of Sykes and others, the Ron Johnson of this campaign is far different from the Ron Johnson of campaigns past. These days, he might be more aptly described as a Midwestern Republican rooted in the far-right fever swamps.

Johnson has spent much of his second term amplifying conspiracy theories and making outlandish claims, particularly about the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccinations, Jan. 6, and the investigations into Donald Trump.

Johnson, a 66-year old who married into a plastics company that eventually made him a multi-millionaire CEO, is seen by Republicans as actually having a claim to that elusive “outsider” mantle so many politicians strive for. In 2010, he’d never run for political office; he first gained notoriety because Sykes read one of his speeches on the air. He is as comfortable chugging a beer as he is calmly amplifying skepticism of life-saving vaccines.

As he faces a challenging campaign, Johnson is, if anything, expected to dial up the rhetoric that has made him one of the left’s most hated senators and an unlikely hero of the right. His own record of proving doubters wrong—including those in his own party—has imbued him with a particularly defiant desire to stick it to his growing legions of critics, observers say.

In a brief interview in the Capitol on Wednesday, Johnson previewed his campaign, saying he would focus on “just all the Democratic policies and the results of them.” He specifically mentioned illegal immigration, the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan, historic rates of inflation, and the federal deficit.

“Their campaign,” Johnson said of Democrats, “will be a campaign of personal destruction. They’ll try to destroy me personally. I’ll be talking about the issues. They can’t defend their policies.”

Sykes, who was so instrumental in Johnson’s rise that the senator once credited the pundit with getting him his position, is now a vociferous critic of the man he now calls “RonAnon.” He predicted that the 2022 campaign will be an unfettered expression of Johnson’s surly brand of politics and that he would run a “scorched-earth” and “sharp-edged” campaign.

“This is a vindication campaign for him,” said Sykes. “This will be very much the Ron Johnson id. He’s going to let the freak flag fly.”

It is not a stretch to say that control of the Senate—currently divided evenly between the parties—may rise and fall on the script of this campaign. Johnson is the only Republican incumbent up for re-election in a state Joe Biden won in 2020. With several incumbent Democrats facing tough races elsewhere, a Johnson defeat could help ensure Democrats continue to control the chamber, while his win may assure that Republicans take control of the chamber.

Ron Johnson (R-WI) questions Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz during a Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs hearing on December 18, 2019.

Samuel CorumIn an election that could be decided by just thousands of votes, Johnson’s newfound reputation as a consistent source of outright false—and sometimes truly wacky—claims might seem like a serious liability.

In 2019, Johnson first found himself regularly in the national news cycle by spreading discredited allegations of corruption against Biden during President Donald Trump’s Ukraine impeachment saga.

After Trump lost in 2020, Johnson publicly flirted with the big lie of widespread election fraud, and did not acknowledge Biden’s win. Privately, he allegedly knew it was all false. In December 2020, a county GOP official in Wisconsin wrote in The Bulwark that Johnson said he knew Biden won but claimed it would be “political suicide” to admit that fact.

On Jan. 6, Johnson intended to object to the counting of electoral votes, but moved to certify the state counts after the attack on the Capitol. In the aftermath of the attack, however, Johnson has contributed to the pro-Trump revisionist history around Jan. 6 by amplifying denialist claims—such as the theory that the Capitol was stormed by “friendly” protesters—and blaming Speaker Nancy Pelosi for the violence.

The COVID pandemic, meanwhile, has provided frequent opportunities for Johnson, who appears semi-regularly on cable television, to offer bizarre opinions frequently untethered to the medical and public health consensus.

The senator has publicly encouraged people to protect themselves from the virus using methods such as hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, and, most recently, mouthwash. At the same time, he has used his public profile to cast doubt on safe and effective COVID vaccines, asking last week, “Why do we think that we can create something better than God in terms of combating disease?”

For all of Johnson’s outlandish rhetoric, you might think Democrats would make hay of his comments. Johnson does, after all, seem to provide new targets every week. But interestingly, their strategy seems to hinge on doing the opposite.

During an interview with The Daily Beast, Wisconsin Democratic Party Chairman Ben Wikler did not mention any of Johnson’s headline-grabbing comments until he was specifically asked about them.

Instead, Wikler immediately focused his attacks on Johnson’s voting record—particularly his votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act and his considerable influence on the GOP’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017.

“Johnson’s attacks on democracy, science, and common sense certainly disqualify him from public life,” Wikler said. “At the same time, it’s clear from the last five years that people vote more on what affects them than what offends them.”

Those who have worked for Johnson say that he, more so than many politicians, defines the campaign he wants to run; he’s said to have only limited regard for the advice of consultants.

Many Republicans believe that approach has, clearly, worked for him. “He keeps his own counsel,” said a Wisconsin Republican operative. “You’ll continue to see Ron Johnson do his own thing.”

Mark Graul, a Republican strategist in Wisconsin, has advised Johnson during his past campaigns. “As someone who has been in meetings with him on messaging, you don't script Ron Johnson,” he said.

Democrats—and Republicans—have underestimated Johnson before. In 2016, he was so widely expected to lose his rematch with the former Democratic senator, Russ Feingold, that his own party wrote him off: late in the campaign, PACs aligned with GOP leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) cut their TV ad spending to support the incumbent. He ended up winning by nearly 4 points, as Trump became the first Republican presidential candidate to carry the state in decades.

Democrats are determined not to have a repeat performance in 2022. Joe Zepecki, a Wisconsin-based Democratic strategist, said that 2016 was a “wake-up call” and that Wisconsin Democrats “have not taken a single statewide office for granted ever since.” In 2018, the state re-elected Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin and elected Democrat Tony Evers to replace Gov. Scott Walker.

Still, Democratic and Republican observers agree on an odd dynamic shaping up in Wisconsin right now—that Johnson is the rare candidate who both parties want in the race. Republicans prefer to have a battle-tested incumbent and no messy primary; Democrats like their chances against an incumbent they view as deeply flawed.

That truth, says Zepecki, “breaks my brain a little bit.” But he added it was quite possible that Ron Johnson is the only Republican who could lose this seat.

“We could wake up on December 1st and find that Republicans swept all battleground races and lost Johnson,” Zepecki said.

Johnson’s consistently poor polling in the last year seems to animate that sentiment. In November, a Marquette University survey found that 38 percent of respondents would vote to re-elect Johnson, while 52 percent would vote for “someone else.” Those numbers would suggest that Johnson is just as, if not more, vulnerable than top Democratic targets of the GOP in battlegrounds like Arizona and Georgia.

The Democratic primary field in Wisconsin is crowded with hopefuls who believe they can finally unseat Johnson. Mandela Barnes, the lieutenant governor, is considered the frontrunner, given his advantages in polling and fundraising. But there are other competitive candidates clearly in the mix, including Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson, state Treasurer Sarah Godlewski, and Milwaukee Bucks executive Alex Lasry.

Wisconsin Republicans are attacking all four of them, working to paint whoever emerges as, well, extremely left-wing. “Democrats are tripping over themselves while they fight over who is the most liberal in hopes of pushing their far-left policies,” said a Wednesday release from the Wisconsin GOP.

Most of these Democrats are sticking to the strategy that Wikler outlined: attack Johnson more on his votes, less on his opinions about things like Jan. 6.

Godlewski’s first tweet hitting Johnson after he officially announced his re-election bid, for example, served as a reminder that he “held up $1,400 checks and tried to block COVID relief.” Others went at something Democrats see as a crucial strategy: tying Johnson to wealthy special interests.

A major opportunity to advance that case is Johnson’s influence on the 2017 GOP tax bill. He threatened to hold it up, potentially derailing it, but ultimately got on board.

Later, ProPublica reported that he demanded the bill include a new tax deduction for so-called pass-through businesses. He succeeded, and the change yielded hundreds of millions of dollars in collective savings for some of Johnson’s biggest political donors. Johnson defended himself by saying he felt the change he pushed for was broadly beneficial.

Barnes’ first tweet on Johnson’s announcement referenced this storyline. “Ron Johnson has sold out the people of Wisconsin for his big donors and for himself,” Barnes said.

Wikler, who as party chair is neutral in the primary, said “the party’s job between now and August is to help inform Wisconsin voters about Johnson’s terrible, self-serving record… to make sure his polling stays as terrible as it is right now, in other words.”

Republicans do not seem bothered by this, saying that such polling is a side-effect of Johnson being Johnson.

“He is very much himself, all the time, when it comes down to it,” said the Wisconsin GOP operative. “It hasn’t gotten him in trouble with his constituents.”

That’s been true so far, but whether Johnson gets another six years in power depends on whether or not enough of his constituents believe, like Sykes, that he is not the same person who earned their votes in 2010 and 2016.

To some Democrats, it’s not mutually exclusive to argue that Johnson both sold out his aw-shucks image and bought into the fever swamps.

“He has taken to Washington and the tribal warfare of partisan politics like a fish to water, in a way that is astounding,” said Zepecki.

But ask why, and even those who understand Johnson best—or used to—are left scratching their heads.

When asked why he thought Johnson has changed over the years, Sykes sighed. “I don’t really know,” he said. “I used to have a number of theories. But they’ve all been overtaken by the craziness.”