The Guantanamo Bay military tribunals on Wednesday won their first conviction without a plea deal since 2008. Only it wasn’t a terrorist who was convicted – it was a one-star Marine general sticking up for the rights of the accused to have a fair trial.

In defending the principle that attorneys ought to be able to defend their clients free from government surveillance, Brigadier General John Baker was ruled in contempt of court and sentenced to 21 days in confinement. He also must pay a $1000 fine.

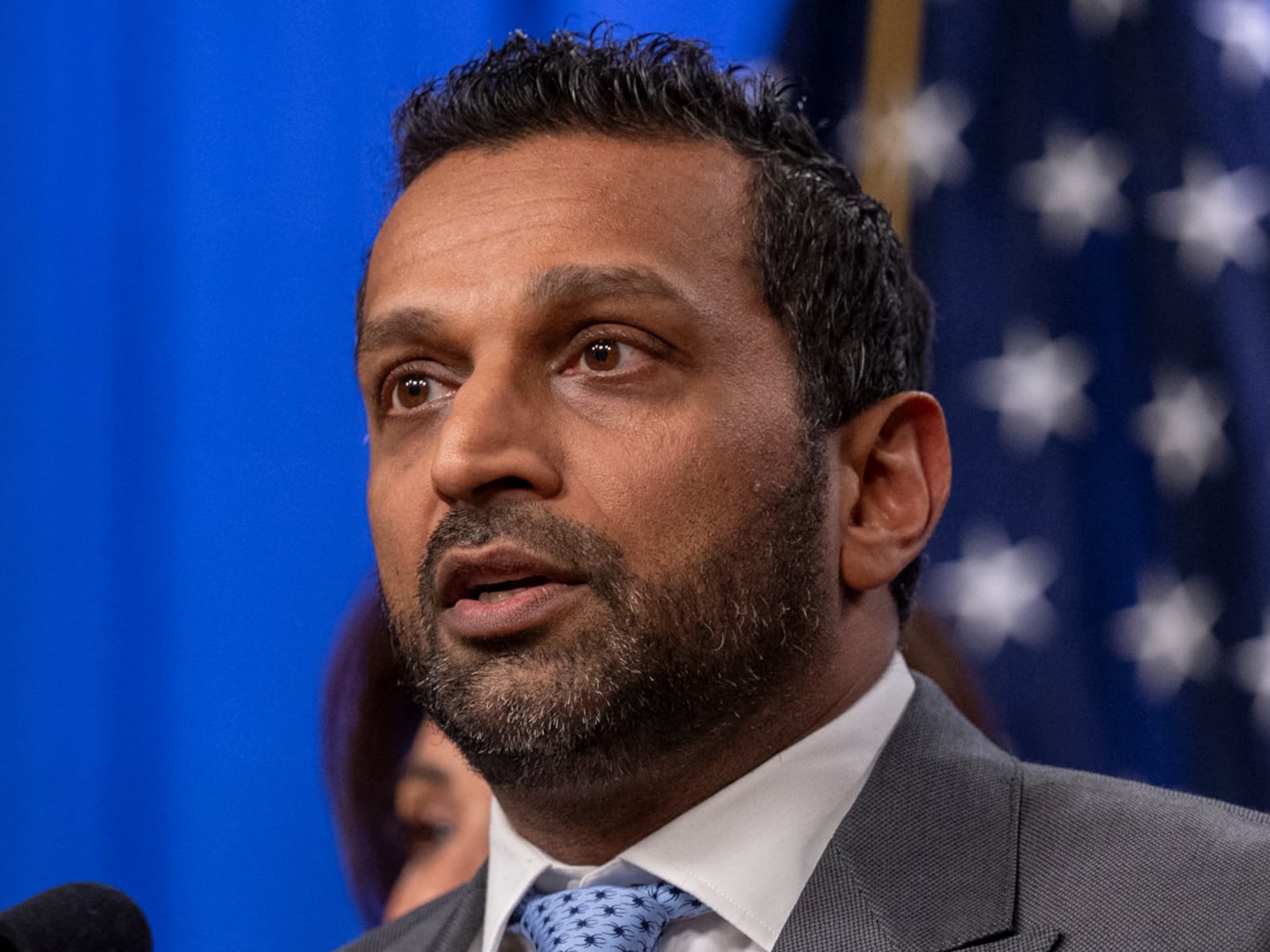

Baker is a senior officer within in the highly controversial military commissions process: the Chief of Defense Counsel. Maj. Ben Sakrisson, the Pentagon spokesman for detentions, confirmed that Baker is being confined in his quarters – at Guantanamo Bay.

“The military commissions are willing to put people in jail for defending the rule of law,” Jay Connell, who represents another Guantanamo detainee facing a military commission, told The Daily Beast. “If they’re willing to put a Marine general in jail for standing up for a client’s rights, they’re willing to do just anything.”

Baker’s sentence Wednesday was first reported by Carol Rosenberg of the Miami Herald, the only reporter actually at Guantanamo and who saw the hearing. He outranks the judge who sentenced him, Air Force Colonel Vance Spath.

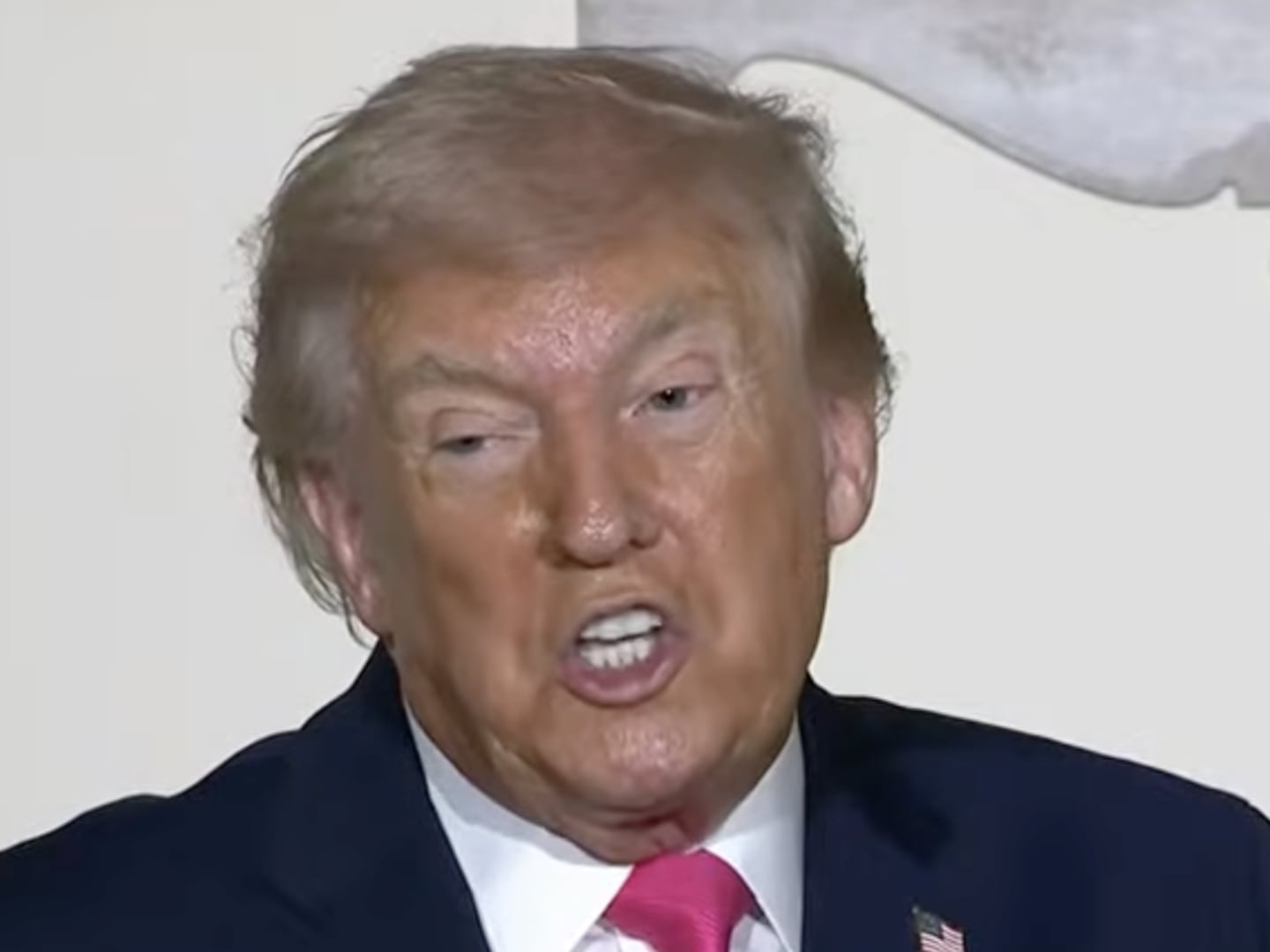

The shocking development at Guantanamo, described as a “national disgrace and an embarrassment” by the executive director of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, came on the same day President Donald Trump publicly mulled detaining accused New York terror suspect Sayfullo Saipov at Guantanamo. (As a lawful permanent resident, Saipov is likely ineligible for a war-crimes trial under the 2009 Military Commission Act, which specified the court is for non-Americans, even if the Pentagon decided his alleged acts rose to the level of a war crime.)

The path that led to Baker’s contempt confinement started with a group resignation and a clash with Spath.

Earlier this month, three civilian attorneys for Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the accused bomber of the USS Cole in 2000, abruptly quit the death-penalty case. The attorneys said that they had significant reason to believe the government was listening in to their communications. Spath, the judge in the Nashiri case, barred them from discussing the issue with Nashiri, since it was classified. Nashiri had lost his lawyers without ever knowing exactly why.

It is not the first time that concerns over government spying have rocked the Guantanamo military tribunals. In 2014, pre-trial hearings for the accused 9/11 co-conspirators snarled after defense attorneys revealed indications that the FBI had turned their technical adviser into a secret informant, prompting the judge in that case to prohibit monitoring attorney-client communications in November 2016. And in 2013, in the same case, the CIA cut the audio feed at the war court before an attorney discussed an aspect of the defendants’ confinement at undisclosed CIA “black site” prisons.”

Baker supported the Nashiri attorneys’ decision to quit – and believed he, as chief defense counsel, had all sufficient authority to permit them to walk. Baker released them on October 11. But, facing the prospect of the Nashiri death-penalty commission snarling to a halt, Spath disagreed, and ordered them to return to Guantanamo.

Instead, Baker showed up at the war court this week, without now ex-Nashiri attorney Rick Kammen and Kammen’s team. Spath instructed Baker to change his mind and instruct Kammen and the two other attorneys that they still represent Nashiri. Baker did not, believing that Spath lacked the authority to do so. On Wednesday, Spath held Baker in contempt and ordered him to 21 days’ confinement in his Guantanamo quarters.

Connell, who represents 9/11 co-defendant Ammar al-Baluchi, said all this could have been avoided had the government simply not spied on the Nashiri team, “or allowed the defense counsel to discuss this issue with their client.” He added that Baker’s sentencing did not settle the issue of who in the military commissions process – a judge in a specific case, or the Chief of Defense Counsel – has final say over an attorney quitting.

“It will come up again the next time someone tries to resign or otherwise leave the case,” Connell said. He did not know if other Guantanamo defense lawyers would resign in protest.

Baker had a history of supporting unmonitored attorney communications, which are a bedrock principle of civilian trials. In June, shortly after learning of the suspected surveillance on the Nashiri lawyers, he advised defense attorneys “not to conduct any attorney-client meetings at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (GTMO), until they know with certainty that improper monitoring of such meetings is not occurring,” according to a letter obtained by the Miami Herald.

“At present,” Baker continued, “I am not confident that the prohibition on improper monitoring of attorney-client meetings at GTMO as ordered by the commission is being followed.”

It’s possible that Baker won’t serve out his sentence. Harvey Rishikov, the convening authority of the military commissions, “will determine whether to affirm, defer, suspend or disapprove the sentence in the next few days,” the Pentagon’s Sakrisson said.