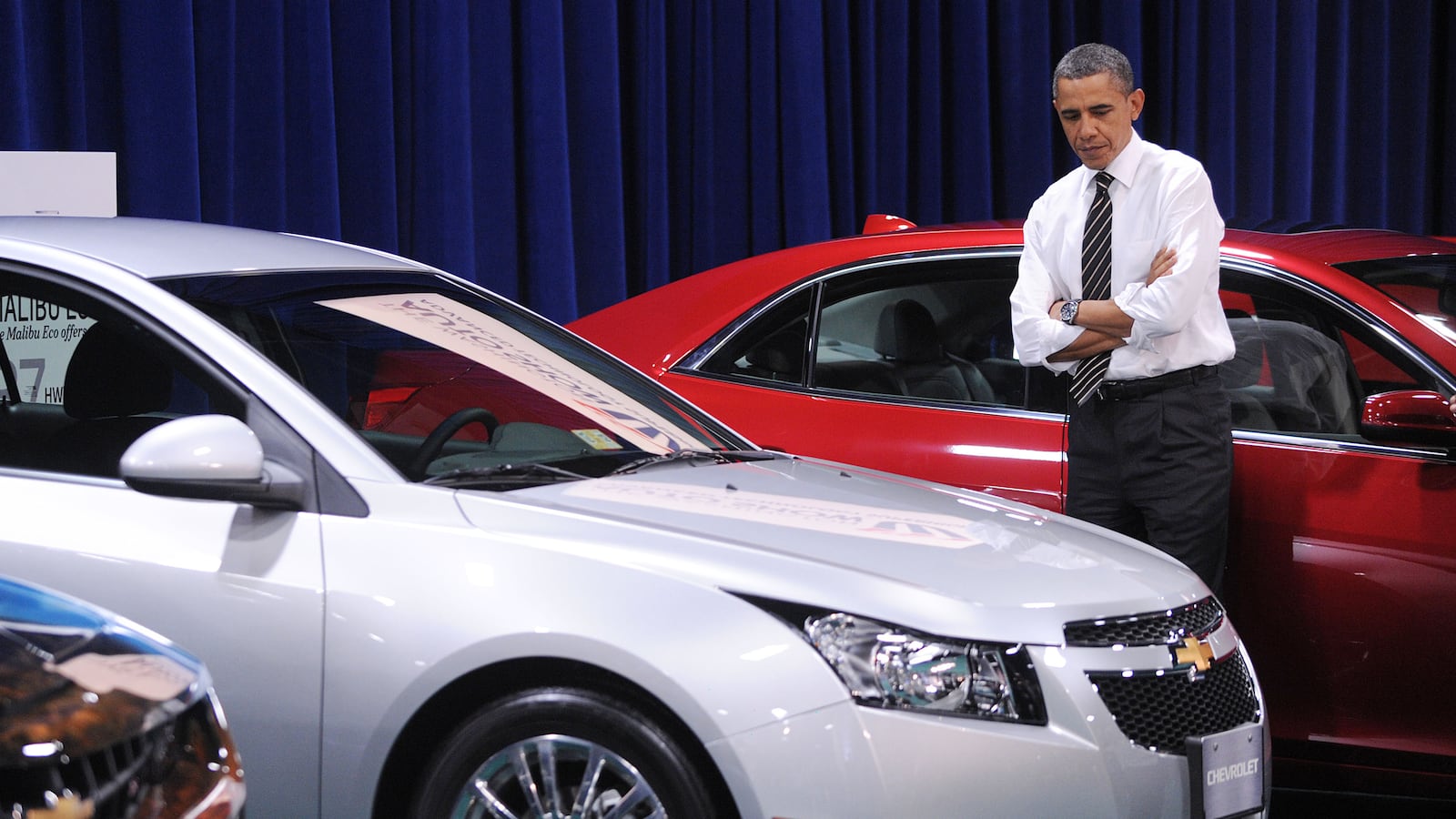

When General Motors went bankrupt in 2009 and had to accept a federal bailout, its critics—and rivals—referred to the company derisively as "Government Motors.” The implication? Far from being a dynamic private sector entity, producing vehicles and innovating, it was a bureaucratic arm of the Obama administration. Managers, workers, and other stakeholders would go about their day with the government perpetually looking over their shoulders and telling them how to run the business.

Of course, aside from clamping down on businesses and instilling a fear of using corporate jets, the Obama administration didn’t micromanage G.M. General Motors went public in the fall of 2010. Soon thereafter, the government started selling its shares in the company. Treasury sold the last of its shares in December 2013, closing out the investment with a $10 billion loss.

Six years ago, the failure of G.M.’s financial engineering brought greater government oversight. Now a failure of electrical and business engineering is turning G.M. into Government Motors again.

The long-running saga surrounding problematic ignition switches for the Chevrolet Cobalt has been an embarrassment for G.M. A problem that could have been averted at a relatively small cost wound up causing accidents that killed 13 people. And the botched response has brought down the government’s wrath on the company. In doing so, it has thrust the strong arm of the government directly into the company’s operations.

First, the National Highway Transpiration Safety Administration (NHTSA) came down as hard as it could Friday on General Motors. “What NHTASA is doing is the most it can do under the existing law,” said Clarence Ditlow, director of the Center for Auto Safety in Washington, D.C. NHTSA levied a $35 million fine against G.M. It may seem like a slap on the wrist, but that is the hardest hit allowed.

Typically, a fine and a promise to behave better gets companies off the hook. But NHTSA has promised “unprecedented oversight requirements” that will have the agency up in the company’s grill. NHTSA is demanding that GM changes the way it does business when it comes to putting cars together and dealing with problems and defects. In addition to the fine, NHTSA “ordered GM to make significant and wide-ranging internal changes to its review of safety-related issues in the United States, and to improve its ability to take into account the possible consequences of potential safety-related defects.” As part of the consent order signed Friday, NHTSA will micromanage G.M.’s internal investigation and recall efforts, specifically prescribing initiatives such as “including targeted outreach to non-English speakers, maintaining up-to-date information on its website, and engaging with vehicle owners through the media.” What’s more, G.M. must “submit reports and meet with NHTSA so that the agency may monitor the progress of G.M.'s recall and other actions required by the consent order.”

Stockholders took the news in stride. The company’s stock barely budged on Friday, treating the consent order as a non-event.

But there’s more to come—and G.M. still has plenty to fear from the federal government. The Justice Department has far more tools at its disposal to punish corporations for such episodes than NHTSA—large fines, jail sentences, and big plea deals. And in March started looking into General Motors.

While Justice has been slow to pursue criminal cases against blue-chip financial corporations, it has shown less restraint when going after automakers. In March, the Justice Department formally charged Toyota in a criminal case that carried a $1.2 billion penalty over issues relating to misleading consumers about issues with gas pedals sticking, which was responsible for up to 21 deaths. It was, the Justice Department noted, “the largest penalty of its kind ever imposed on an automotive company.”

What’s more, the G.M. investigation is being led by the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. Led by Wall Street scourge and prosecutor Preet Bharara, the Southern District has an epic undefeated streak prosecuting insider-trading cases and relishes going after high-profile defendants. (On Friday, hedge fund trader Michael Steinberg was sentenced to 3.5 years in jail for his insider-trading conviction.)

So as G.M. labors to comply with the consent order imposed by NHTSA, it will have to cope with the prospect of an expensive prosecution. “I cannot believe Justice will not impose a fine larger than what it did against Toyota,” said Ditlow. The real question remains to what degree Justice will pursue criminal charges against the company, or against specific individuals.

The government gave plenty to G.M. in 2009 and 2010. It now has the potential to take plenty away.