ST. LOUIS—Just before daybreak, sitting at the edge of her bed in an upper bedroom, she clutched her pale blue housecoat and listened tearfully to the transistor radio on the nightstand. At the top of the hour, a familiar, melodic voice confirmed what she already knew: Her husband was dead.

It had been a tumultuous relationship, at times beautiful and at others marred with ugliness. They were separated and had been for several years, living worlds apart and with other people now, but he was still hers—still her husband and the father of her youngest child. The news that he had been murdered—found shot in the head and pronounced dead on arrival at a city-run hospital—was devastating.

She’d gotten the fateful call from nightclub owner Gene Norman—who doubled as a disc jockey on KATZ-AM 1600—as she closed her shift as a cocktail waitress at The Windjammer. She left the bar, situated atop the Marriott Hotel near Lambert Field, and began the 20-mile drive home east along Interstate 70. As she crossed the Mississippi River into East St. Louis, Norman took to the airwaves and dedicated a song—Gladys Knight’s “Midnight Train to Georgia”—to “Jerry.”

…he couldn’t make it,so he’s leaving the life he’s come to know…

It was still dark out when she pulled into the public housing complex in the Duck Hill neighborhood. She wailed, screaming and shaking in her car.

…I’d rather live in his world,than live without him in mine…

I watched my mother descend the stairs that Sunday morning. Overcome with grief, her voice breaking and her body still trembling, she reached for me. “He’s gone,” she whispered, grabbing me with both hands. “Your daddy was killed.”

It was 1973 and I was 5 years old. Even then, I knew what death meant. As our family gathered at Aunt Geraldine’s house on 10th Street that evening, my uncle held me through the night. I curled up in his lap and sobbed until I slept.

I am 48 now, with grown children and grandchildren of my own, but—in so many ways—those tears have never stopped falling. I still think about him every day—how our lives might have been different, about who killed him and why. Some 43 years later, his murder remains unsolved.

In the months and years following his death, relatives floated theories when they thought I wouldn’t understand or was out of earshot. I quietly tallied the names and places as I listened to grown folks recount pieces of the story, some fact and some folly, over liquor and card games.

When I was old enough to ask questions, few answers came. Each person I asked came to the same dark, dead-end alleyway and stopped. For my father’s mother, Catherine, and for my mother, Mary Alice, I know, the memories were far too painful.

“Let sleeping dogs lie,” Grandmother Catherine said, repeatedly, until I stopped asking.

When Grandma Cat died in 1994, I’d started digging through old newspaper clippings and scouring court documents for clues, finding loose threads to pull on in the story that no one—whether out of fear or loyalty—would tell me. In doing so, I discovered things about the man my father had been, things that made it tough to keep going. It could not have been easy to love this “dreamer” with “delusions of grandeur,” as my mother described him—certainly not to love him as hard and as thoroughly as both she and my grandmother had.

He kept dreaming,That someday he’d be a starBut he sure found out the hard way,That dreams don’t always come true…

With stops and starts, I have spent decades looking for answers, slowly and methodically stitching together the fabric of a story no one would talk about. New questions and new answers have emerged over the years as I chased down a faceless killer. But in the end, I came up short—unable to answer the driving question: Who murdered my father?

My search ended where it had begun: with a man named Roland B. Norton Jr.

***

Roland was a desperate man—desperate to survive the violent drug war brewing in north St. Louis and desperate to stay out of prison. Charged with two counts of dealing heroin, Norton was quickly released on bond and hit the street with one end in mind: find the government informant threatening his freedom and kill him.

In the weeks leading up to his November 1973 federal drug-trafficking trial, two men were shot, in separate incidents, execution-style. The second man, Wyart Taylor, was my father. He was found, blocks from his house in north St. Louis, face down on a sidewalk in a pool of blood.

A grand jury indictment—announced by Donald J. Stohr, the U.S. district attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri in the fall of 1973—spelled out the damning case against Norton, who was suspected of having connections to at least two notorious drug rings that kept north St. Louis awash in “brown sugar” and “snow.” On Aug. 10 of that year, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that 24-year-old Norton—who was then employed as an auditor in the city license collector’s office—and another man named Bernard Pratt were allegedly part of a “large-scale narcotics sales operation.”

Secured in March, the Norton indictment had been sealed for nearly six months to protect the identity of a federal witness and the integrity of other ongoing investigations. However, once Norton was arrested that August, the document became public and Norton immediately launched a city-wide manhunt for the witness.

Eager to unmask the unnamed informant, Norton’s defense attorneys filed a “bill of particulars” on Sept. 6, demanding that the government “furnish him with the time, place, and name of the party, if there is any, who are witnesses to the transactions.” They also moved to dismiss the indictment on the grounds that “the delay had prejudiced his ability to present an effective defense, thereby violating his Fifth Amendment right to due process.”

The judge in the case, John F. Nagle, denied both motions, leaving Norton to guess who was cooperating with the FBI and DEA.

According to court records, there were two transactions on or about Feb. 26 of that year—one for $350, the other for $500, together weighing 3.9 grams—and, based on that information, Norton figured out who set him up. Just over a month after the indictment was unsealed and the defendant was released on bond from federal custody, Michael “Big Mike” Jones was tracked down and killed on Sept. 17. Although he was not among the listed witnesses and had no known drug involvement, the second man—my father, Wyart—was murdered on Nov. 5 as he walked home from an illicit card game.

Norton—the son of a disgraced St. Louis police officer—was never charged in the murders, nor is there any evidence that he was an official suspect in either shooting. According to Grandma Cat, local authorities quickly wrote off both as robberies gone bad and she said the investigations were summarily closed. When she went downtown to police headquarters to offer a cash reward for information about her son’s murder, the desk sergeant allegedly told her, “Go home, lady. Nobody cares who killed your boy.”

But the streets were whispering about the likelihood that Norton, also a reputed pimp who was said to be fond of fine clothes, flashy jewelry, and beautiful women, was involved. Before his arrest on federal drug-trafficking charges, Norton enjoyed the high life—replete with full-length fur coats, silk-ribboned wide-brimmed hats, and scantily clad, cooing cocktail waitresses who answered at his beckoning. Despite those trappings, and a well-paying city job secured with his father’s connections, he frequently borrowed money from a local loan shark named “Papa Joe” Henry.

The younger Norton also relied heavily on his father, with whom he still lived in the 4500 block of McMillan Avenue at the time of his indictment.

From the first time I overheard his name in the early 1980s, I was told Norton was the son of a Korean War veteran and “dirty cop” said to have taken bribes to protect area drug dealers and underground nightclubs, and to have fed police information to Italian mobsters. How much of what my older cousins said was fact or folly I did not know. However, some of that information was confirmed recently when I learned that Norton Sr. had been brought up on decidedly thin charges of public corruption and demoted by the St. Louis Police Department in 1959, after just three years on the force. He resigned five years after that, amid a second investigation into allegations of wrongdoing and after he’d allegedly been seen frequenting a “tavern of ill-repute” as an off-duty officer.

“The formal charge cited specific instances” that he was “alleged to have collected admittance fees, removed objectionable customers and closed the doors at closing hours.” He had also “associated” with a “woman wanted for burglary.” Two years later, in 1966, Norton Sr. was shot in the leg during an altercation over “a strip tease dancer.” Tragically, his wife, Ellyn, was killed along with two others in a 1970 car accident on Illinois Route 127, just north of Greenville, Illinois, after another vehicle crossed the centerline and struck them head-on.

By 1973, Norton Sr. was a widower living on his military pension who did not have the means to make his son’s five-figure bail. A few months ago, I tracked down a woman, a family acquaintance who had been the live-in girlfriend of a rival drug lord. She hesitantly told me that a pair of Norton Jr.’s midlevel drug captains posted the $50,000 cash bond. I was unable to find a trace of either man in public records, but she said they were looking after their own interests. The drug-runners needed Norton out of jail, away from federal agents and potential jailhouse informants. They need Norton to “handle that business,” the ex-girlfriend told me.

The government witness needed to be found and silenced.

When Norton was first taken into custody, investigators reportedly pressured him about his ties to drug gangs operating in St. Louis—including the notorious Petty Brothers—and offered him a deal that included immunity but no federal protection. Norton refused to tell FBI and DEA agents who he was working for. “Roland ain’t wanna die,” the rival’s ex-girlfriend said, “and he damn sure ain’t wanna to go to jail.”

Norton had few real options and, the way he saw it, there was just one way out. He knew who made the buys from him based on the dates and amounts listed in the indictment. Prosecutors believed by sealing the indictment against Norton they were buying time to make headway in breaking up a suspected ring of high-end dealers and put an end to the bloodshed. The document, unsealed by federal law upon Norton’s arrest, might as well have been a death warrant.

“Big Mike was a dead man walking,” an older female cousin told me.

Described by my cousin as a large “flamboyant gay man,” Big Mike was making a decent living setting up dealers for the federal investigators. He was “a small-time hustler,” she said, and court records confirm that Jones was actively helping in several cases.

“Bodies were dropping every other day,” my cousin, who was once engaged to one of St. Louis’s most notorious crime bosses, told me.

Few—even my cousin—would talk with me on the record without anonymity about the drug war that was touched off in the early 1970s and lasted into the early ’80s. Almost no one wanted to talk about the violence—which included car bombings and movie-theater shootings—that littered the nightly newscasts.

But Dennis Haymon, a former drug kingpin himself who led one of the area’s deadliest gangs, knew both Norton and Jones well. My cousin told me about Haymon, and I quickly found him still living in St. Louis.

Haymon remembers that Big Mike was a drug addict “who knew how to get money.” Jones, he said, was also a well-known “booster” and a “money-getter” who peddled stolen goods around the corner of Pendleton and Finney avenues.

Despite Norton’s legal predicament, he wasn’t “a real killer,” Haymon, who was once one of the most feared men to walk the streets of St. Louis, told me over a series of phone calls spanning hours in recent months. Now an ordained minister and an anti-gang activist writing his memoirs, Haymon served 25 years of a life sentence after he was convicted on murder charges in 1979.

Haymon confirmed what I’d read in old newspaper clips, that he had been locked in a bloody war with the Petty Brothers—Samuel, Lorenzo, and Joseph—for nearly a decade. In one incident, he said the Pettys climbed atop a nightclub and sprayed a crowd with bullets in a failed attempt to kill him. Five club-goers were shot and a woman standing five feet from Haymon was killed in the incident, but Haymon got away.

My family had been close to the Pettys when I was growing up. As a child, I had been fond of Joe—who was engaged to my cousin and fathered two of her now grown daughters. He was a good-looking man with wide, nickel-sized eyes and a full beard. I remember how he had always been especially kind to me, even helping me land my first job at 14 as a dining-room attendant in a downtown St. Louis restaurant that was reputedly run by the mob.

I knew nothing of about his life as a drug dealer or about the string of gangland shootings in which he had allegedly been involved. Joe had been shot once, I knew, while sitting outside a convenience store that he owned. He refused to talk to the responding police officers about the incident, saying only that he would “take care of it.”

When I asked him about my father back in 1983, Joe kissed my forehead and said, “You can’t bring him back.”

Joe, who died after a suspicious motorcycle accident the following year, used to tell me how much I looked like my father. If he knew what happened to him, he never said, and that secret was buried with him. But in so many ways, Joe had been my protector. A once stern music teacher in junior high school suddenly treated me more gently after she learned that I had family ties to Joe. I never met his brother Sam, an ex-convict who was sent away on federal drug-trafficking charges and died of bone cancer in the 1990s.

But recently, I contacted Lorenzo—the only surviving brother—after cajoling a mutual acquaintance for his cell number. Though I had never actually met Lorenzo, I had always been told that he was an “evil” man. His first arrest came in 1964, at just 15 years old, when he stabbed 21-year-old Leroy Chappel over 25 cents.

“Lorenzo is one mean dude, and just about everybody is scared to death of him,” a detective said after he was arrested in 1978. “Maybe, just maybe with him being locked up, things will cool down.” A search warrant for his Northwoods house turned up sticks of dynamite, assault rifles, ammunition, and a bullet-proof vest.

My fingers twitched as I dialed the number. I stammered, at first, then told him why I was calling.

“I can’t help you with that,” Lorenzo said, repeatedly, as I peppered him with questions about Roland Norton Jr. and Big Mike Jones. He hung up at the mere mention of my father’s name.

If the Petty Brothers knew what happened to Big Mike or my father, those secrets will almost certainly die with the last of them. I phoned Haymon again, pressing him for more details.

“Roland was soft,” Haymon—the only person willing to talk on the record with his name attached—said of Big Mike’s murder. “He had problems pulling the trigger.”

A second, unidentified man supposedly took the pistol from Norton and finished the job.

But even with Big Mike dead, there remained at least one potential witness to testify against Norton—one of his closest associates, in whom he confided nearly everything and to whom, a source said, Norton purportedly owed “a piece of money.”

Seven weeks after Big Mike was killed, minutes after a resident on Kossuth Avenue called police to report shouting and gunshots, a 30-year-old man was discovered face down on the sidewalk. The victim had been shot four times in the head, at close range, with a .22 caliber pistol. Three rounds were still lodged in his brain. The last blast entered his left temple and exited the right side of his face.

“Die nigger. Nigger, die quick,” the gunman reportedly said, according to the St. Louis Daily Whirl, a notorious local crime tabloid.

Given the circumstances and the coroner’s report, I thought it had to be more than a “robbery gone bad,” as my grandmother had been told. Everything I knew about my father’s killing—four bullets to the head at close range and the words allegedly said as he lay dying—suggested it was personal. The shooting reeked of vengeance and malice. And the more I learned about Norton and his connections to St. Louis’s underworld, the more convinced I became that my father’s association with Norton had cost him his life.

How much did my father actually know about Roland Norton’s dealings? Was he one of the government’s witnesses in the federal drug case? Was he in league with the drug gangs that ruled the streets of St. Louis? And perhaps more critically, was my father the trigger man in the murder of Big Mike Jones?

Candidly, there were moments when I did not want to know the truth. Over four decades later, I know that most of those questions will go unanswered. To find some of them, I had to search the annals of my own family history.

***

Florence Blackard (née Carroll) was a drug-addled prostitute. In the mid-1930s, my great-grandmother was penniless and estranged from her husband, Murray, when she was forced to give up her two daughters after child services intervened. The timid, malnourished girls—marked with old scars, mended bone fractures, and fresh bruises—were led from the rodent-infested apartment on Pine Street that had no running water or electricity.

A busted radiator, situated near a sheet-covered window overlooking the avenue below, emitted no heat. The bone-cold, three-room unit was festooned with cockroaches, rotting garbage, and empty bottles of cheap liquor still in their brown carry-out sacks. A well-used douche bag, stained with a deep red Betadine solution, hung on a hanger in the moldy bathroom.

The beatings, Florence’s youngest daughter, Catherine, would later tell child welfare workers, came almost daily, and they rarely attended school. She and her older sister, Juanita, had been whipped by their mother, she said, with electrical cords and flogged with the buckle end of a leather belt. Social workers also deemed their father, an alcoholic who worked as a janitor and lived in a rooming house, unfit to care for his daughters, who were sent to the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home (now known as Annie Malone Children and Family Services).

In the late 1930s, Catherine and Juanita were adopted by a former “chicken picker” turned “cement mixer” from Middle Fork, a tiny settlement in northeast Missouri near Macon, and his college-educated wife, who hailed from the same town. Raised in The Ville section of St. Louis—once home to tennis star Arthur Ashe, boxer Sonny Liston, comedian Dick Gregory, and Rock and Roll Hall of Famers Chuck Berry and Tina Turner—the girls flourished under the watchful eyes of Thomas Angell Hubbard and his wife, Nina Grant.

Catherine and Juanita, who took their adopted father’s name, spent holidays and summers in Macon enjoying hayrides along with a bevy of new cousins. In old photographs, they appear healthy and well-fed, beaming at the camera and wearing new clothes for the first time.

However, when 15-year-old Catherine became pregnant in 1942, she was sent to live with Hubbard’s family in northern Illinois. She gave birth to her first and only child the following summer.

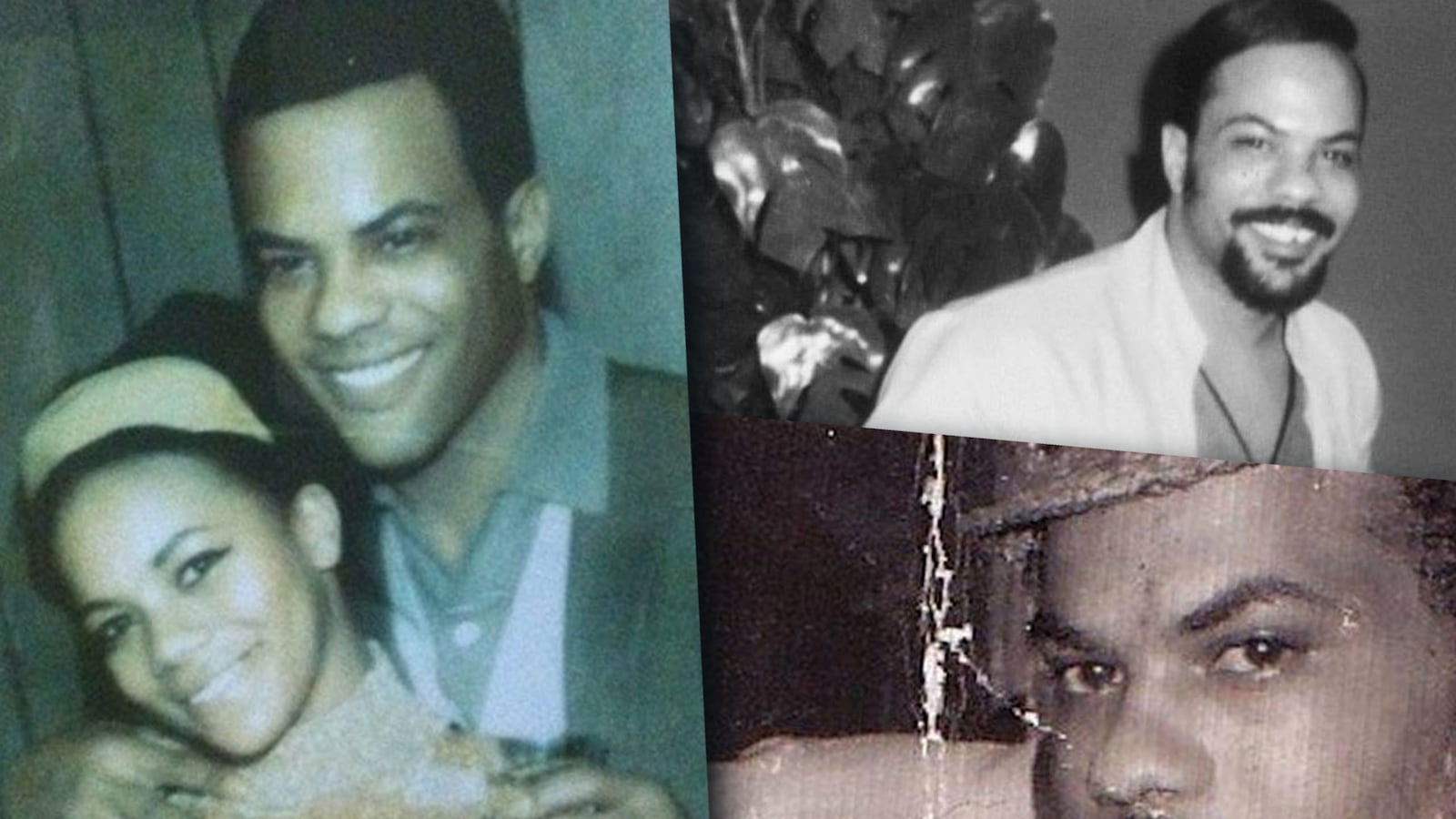

Born on July 17, 1943, in Galesburg, Wyart Taylor Jr. was a slight boy with an apple-shaped cleft chin and serious eyes. With the his biological father largely absent, Catherine married an Army private the following year and moved to Minneapolis, where he was stationed at Fort Snelling.

Catherine, my paternal grandmother, spoke little about her early life and said almost nothing about her life in Minnesota. She did tell me that my father had a son with his girlfriend. In 1963, my oldest brother, Terrence, was born in Minneapolis. I tracked him down in 1993, the year before our grandmother died, when I was 25. At the time, he was a 30-year old Navy officer, stationed in Jacksonville, Florida. Terry, who looks strikingly like our father, never really knew him. It had been my grandmother’s dying wish to see Terry—now retired from military service—and me together. We missed that chance, but he was with me at her small memorial service and, in the years since, I’ve tried to give him the family he missed.

As I came of age, my grandmother enjoyed telling and retelling stories about my father and their exploits, and I’ve shared many of them with my brother. Over breakfast in her Miami kitchen, the retired housekeeper would launch into soaring tales.

There was the time, in 1965, when my father was holed up in a motel room. Four or five armed men, to whom he owed a sizable gambling debt, had the building surrounded. Every exit was covered. According to Grandma Cat, they were careful about who they allowed in or out, and my father didn’t have his pistol.

Cat hatched a plan. At nightfall, she stuffed an overnight bag with three handguns, a box of ammunition, and some old rags. She slipped on an old tattered dress, a floppy hat, and a pair of house slippers. Pretending to be drunk, she stumbled past the men and into the lobby. Once upstairs, grandmother handed over the suitcase of weapons. Cat claimed that she and my father shot their way out of the lobby.

A week later, the same men drove up on my father as he walked to work. Someone sitting in the back seat opened fire. Shot in the upper shoulder, he rolled under a parked car and played dead. He stayed there until his brother-in-law, my Uncle Ross, had the vehicle moved and took him to the hospital.

Years after my biological grandfather—Wyart Taylor Sr.—was crushed to death in an elevator shaft, allegedly by his stepfather, Richard, my father ran into Richard tossing back whiskey shots at a local tavern. Wyart Sr.’s death was ruled an accident but, when my father saw Richard, he promptly introduced himself and, according to my grandmother, he beat the old man to within an inch of his life.

My father was the hero in every story my grandmother ever told.

Cat didn’t talk about the time my father broke a long-neck beer bottle over a bar and sliced a man’s throat for calling my mother a “black bitch.” I overheard my late Aunt Doris Jean saying the man—known on the streets as “Red”—survived, but only because my dad had him dropped off at a nearby emergency room. It was Doris Jean, my Uncle Willie Byrd’s wife who was prone to gossip, who revealed another incident in 1967.

After a neighbor told my father that it was my mother’s nephew who had robbed our house in broad daylight, my father beat him so badly that his jaw had to be wired shut. Because he was family, Daddy then drove my cousin to the hospital himself and paid the bill in cash.

But the year before he succumbed to HIV/AIDS in 1995, my brother Donnie—my mother’s son from a previous marriage—opened up about the beatings he suffered as a child. I will never forget how he broke down that Thanksgiving, sobbing as he told me what my father had done to him.

There were few mentions about my father’s life in the newspapers of the day. I do not know if he was arrested in any of the incidents my grandmother described or others that she would not talk about. But recently, while tracing through the archives of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, I learned that he had in fact been arrested once and charged with aggravated battery related to a fight on March 5, 1967. The charge was upgraded to involuntary manslaughter when the victim, a foreign exchange student, died after languishing on life support at Barnes Hospital.

Bog Soo Byun, a third-degree black belt from Seoul, South Korea, studying engineering at Washington University, suffered a skull fracture after being repeatedly stomped and kicked. His brother Ho Soo escaped with cuts and bruises. They had come to my godmother’s bar, the Gold Room, on the corner of Delmar and Euclid, to take Polaroid photographs and sell them to customers. My father ordered them out. The fight allegedly started when Bog Soo karate-kicked my father, according to defense attorneys.

They told the jury that my father had acted in self-defense.

The trial, held in September 1968, ended in a hung jury, and the charge against my father was abandoned.

Learning of moments like these, I wanted to forget that I was his child. The more I looked, the less he looked like the loving son and devoted husband and father I had been told about. I wondered how a man could truly love his children if he lived that life.

Even though my mother relayed side-splitting stories about her high school classmate, Anna Mae Bullock—who would later become known the world over as Tina Turner—it wasn’t until two years ago, sipping salted margaritas on my sister’s back porch in Tampa, that my mother told me how she met my father. Those were good times, she said, as she giddily recalled spotting the man with movie-star looks walking up the street. Riding in the car with my Aunt Geraldine, she begged her sister to turn around and follow him. She watched as he went into a nearby nightspot.

My mother went home, quickly dressed up in her finest clothes, and went back to the tavern. She sat at the far end of the bar, night after night, watching woman after woman make his acquaintance. He was a hairdresser, she learned, who specialized in bouffants, roller-sets, up-dos, and the women who wore them.

She decided to send him a drink, and that was enough to get his attention. A few weeks later, when he took sick with the flu, she nursed him back to health while his then girlfriend was watching television in the living room.

After a brief courtship, they married in my Grandmother Alice’s living room in a small house on Cabanne Avenue in 1966 and settled in University City. If my math is right, he was 23 and she was 25. My brother Christopher and I were born two years later.

In the summer of ’68, he’d been out on a bender to celebrate his birthday when my mother went into labor. When he stumbled into St. Luke’s Hospital the next day, the nurse said we were “gone.” Thinking his wife and children were dead, he went back to the Gold Room and continued drinking until somebody saw fit to carry him home, where he discovered us happy and healthy. He proudly hoisted his babies onto the bar. I was named after its owner, my godmother, Goldie Holly.

During their time together, he adorned my mother with fur coats and expensive clothes, including Chanel nightgowns, and diamond rings. A sought-after hairstylist who worked nights and weekends at the Gold Room, he frequented social balls and some of the city’s most notable nightclubs with my mother.

Until a few weeks ago, I never knew the details of why she left him, though I had my suspicions. The drinking and the women were likely too much. Until two years ago, when my mother finally began to crack the door on her life with my father, no one ever talked about that snowy night in January 1969. In a drunken jealous rage, he’d slammed my mother’s face through a plate-glass window. That story rests in a keloid scar still visible above her eyebrow. If there were other incidents of violence in our house, my mother never spoke of them.

“Your daddy was the love of my life,” she told me, time and time again. But that night would be “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she said.

She hid her two older children from a previous marriage with her sister, Geraldine, and her husband, Albert Ross, separated her babies, and went to stay with a friend at Fort Leonard Wood until she could figure out where to go. Within weeks, she was living a new life five hours away in Chicago. On April 1, 1969, she started a job as a waitress in a family restaurant at the Marriott Hotel next to O’Hare Airport. She saved her money, got a place of her own, and sent for her children.

One afternoon, my father showed up unannounced at the restaurant, sat in her station, and ordered coffee. He begged for forgiveness. She told me she was too afraid to go back to work the next day.

“You’re a damn fool if you go back to him,” her mother, Alice, scolded. He soon moved to Chicago, took a job at the post office, and continued his entreaties.

Though they never reconciled, in time things cooled and in 1971 they returned separately to St. Louis, where she continued working for a Marriott Hotel near Lambert Field. He later moved in with a woman named Sylvia, and my mother began dating Tony, a diminutive Italian man with his own checkered past who was easy on the eyes. Despite their newfound relationships, my father never gave up on my mother. He cajoled her with sweet talk and gifts, but my mother never took him back. He never stopped being hers.

My father was killed less than two years later.

I sometimes remember more than I want to about him. Sometimes I want to forget the haunting stories and hold on to Christmas mornings and the buckets of pennies he would deliver on my birthday. I still have fond memories of the yellow kite he bought for me from Miss Cherry’s store and how I felt like the luckiest little girl in the world. He’d come to Aunt Geraldine and Uncle Ross’s house in East St. Louis for a family cookout. It was Memorial Day 1973, and he was still trying to find his way back into my mother’s heart.

We never could get that kite to fly.

***

By all accounts, my father was a cautious man who kept few friends and allowed almost no one into his personal space. Fatefully, the night he was killed, he’d decided at the last minute to go to a late night poker game.

He was worried, he’d told my mother—about what and who he did not say—but couldn’t resist the temptation of easy money. He never played back his winnings and knew, if he was sober, when to walk away. Besides, the address in the 4700 block of Kossuth Avenue was less than a half-mile from his job and mere blocks from his house on the corner of Margaretta and Euclid avenues.

Aunt Doris Jean said the invitation came from someone he trusted: Roland Norton.

At closing time on Nov. 5, 1973— just before Norton was set to stand trial in the federal drug case—my father left his part-time job at the Polynesian Room, a Tiki-style local haunt situated on the ground floor of the Carousel Motel on North Kingshighway, and walked to the address he’d been given.

Except there was no game that night.

As he knocked on the door of a dark house on Kossuth Avenue—a narrow, tree-lined street two blocks from his own house—he was hit with a baseball bat and then shot four times in the head with a small-caliber handgun.

Two gold and diamond rings were stripped from his fingers. His gold necklace and the watch his mother had given him for his birthday that summer were also taken, and his empty pockets left turned inside out. The nearest emergency room was less than a mile away, but according to the death certificate, the victim was pronounced dead on arrival at Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

“Live by the sword, die by the sword,” Aunt Doris Jean said of his murder.

Though they never said as much, my conversations with Haymon and others led me to believe that my father might have been targeted because he had been the trigger man in the killing of Big Mike. My grandmother would have strongly disputed that notion, saying my father never shot anyone who didn’t point a gun at him first. However, everything I know about this case—about the trail of violence that seemed to follow my father—says it is possible.

After Big Mike was murdered, prosecutors in the federal drug case against Norton were forced to rely on written statements that detailed his alleged participation in a heroin ring being operated out of the Hi-Note Lounge located in the 4800 block of Delmar Avenue. With Jones dead, on Nov. 26, Norton’s defense attorneys saw another opportunity. They appealed to the court again in an attempt to get the case against him tossed out before a verdict could be rendered.

This time, the defense filed a motion to “dismiss the indictment for failure to produce a material witness for the defendant to interview,” claiming that by not arresting Norton when the indictment was initially handed down and denied the ability to question potential witnesses that he had been irreparably harmed. The irony, of course, was that Big Mike Jones was dead and Norton had likely planned and helped carry out his murder. And, with my father now lying in the city morgue, I found it reasonable to think that Norton’s tracks had been sufficiently covered.

The motion was denied. Norton was convicted on Nov. 28, 1973. He was sentenced to a federal prison camp on Dec. 21, 1973. He lost a subsequent appeal, but would be released within 10 years.

In 1973, Bernard Pratt and former state representative John F. Conley were also found guilty after being charged with selling heroin from the same lounge.

I believe the three men are dead now; I’m certain that Conley and Norton are dead. My older cousin told me Norton was destitute when he “died getting high” in 2002. Few of his surviving associates will talk about him. Some won’t even admit that they knew him, and others, like Lorenzo Petty, simply hang up the phone at the mention of his name.

When I first went looking for Norton, as an 18-year-old, first-semester college freshman in 1986, he was back in federal custody. This time on credit card and mail fraud charges, after he and a live-in girlfriend filled out hundreds of department store applications and made purchases under fake identities. In June 1986, I wrote him a letter in hopes that he could tell me something, anything, about my father. The envelope had been opened but was re-sealed when it arrived in my student mailbox, marked “return to sender.”

Court records show Norton was arrested again in 1988 and convicted the following year for possession of cocaine and heroin with the intent to distribute. U.S. District Judge Stephen N. Limbaugh sentenced the 38-year-old to 41 months at a federal prison camp.

Haymon says Norton didn’t work directly for the Pettys in the early ’70s. But multiple sources confirmed that Norton had a close relationship with the brothers and that they reconnected shortly after his second release from a federal prison.

But if Haymon is right about Norton, he did not have the stomach to kill a man. Over the course of three decades, I’ve had doors slammed in my face, been hung up on, and had mail returned. That silence, and a lengthy conversation with others who knew Norton, left me convinced of two things: Norton was indeed involved in the murders. And at least one of the co-conspirators—maybe even the man who killed my father—may still be alive.

The answers, I have now come to believe, are unknowable. As my father had been when he was alive, they feel just out of reach.

***

I remember the funeral. I remember the throng of mourners, the hundreds of people who filed into the pews at Mercy Seat Missionary Baptist Church on Washington Street—where my maternal grandmother, Alice, had been a member since 1941. Her pastor, Pastor Roosevelt Brown, gave the eulogy.

I remember the baptismal pool, situated high above the pulpit and the choir stand, and the four chandeliers that dangled over the altar. I remember the beautiful brown suit mother chose for him, his jet-black, shoulder-length hair and receding hairline. I remember the white flowers draped over the bronze and gold casket. The smell of lilies never left me. The wailing started when a soloist began singing “His Eye Is on the Sparrow.”

I sing because I’m happy, I sing because I’m free,His eye is on the sparrow and I know he watches me…

One by one, each of us—his wife, his mother, and his children—were escorted to the altar to say goodbye. My mother, brother Christopher, and I were the last to stand, the last to touch him before the funeral director closed and locked the coffin. But I’ve never forgotten the stillness of his face, his perfectly etched mustache and silky smooth skin. And then, the next day, being scooped up by my godmother, carried over the gravel driveway and across the lawn at Greenwood Cemetery off Lucas and Hunt Road on St. Louis Avenue.

Of the boys and men present at the memorial service, almost none have survived. Nearly 20 years after we laid my father to rest, my brother Christopher was shot dead in a remarkably similar ambush, and my brother Donnie succumbed to HIV/AIDS in 1995. The oldest living man in my immediate family, excluding my long-lost brother Terry, was born in 1986. For me, there are no fathers, no uncles, no grandfathers, and no brothers left whom I was raised with. We are a family of women. My mother, who retired after nearly 40 years with Marriott, raised us on her own.

Curiously, a pallbearer discovered a folded two-dollar bill tucked into my father’s suit pocket—an omen, my decidedly superstitious Aunt Doris Jean said, of bad luck. My father’s killer was said to have been among the mourners.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is an excerpt from Taylor’s forthcoming memoir, Let Me Still Be Singing When Evening Comes.