In an extraordinarily rare move on Thursday afternoon, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) withdrew a circuit court judge nomination after Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) indicated that he would not vote for the nominee, causing other Republican senators to follow suit.

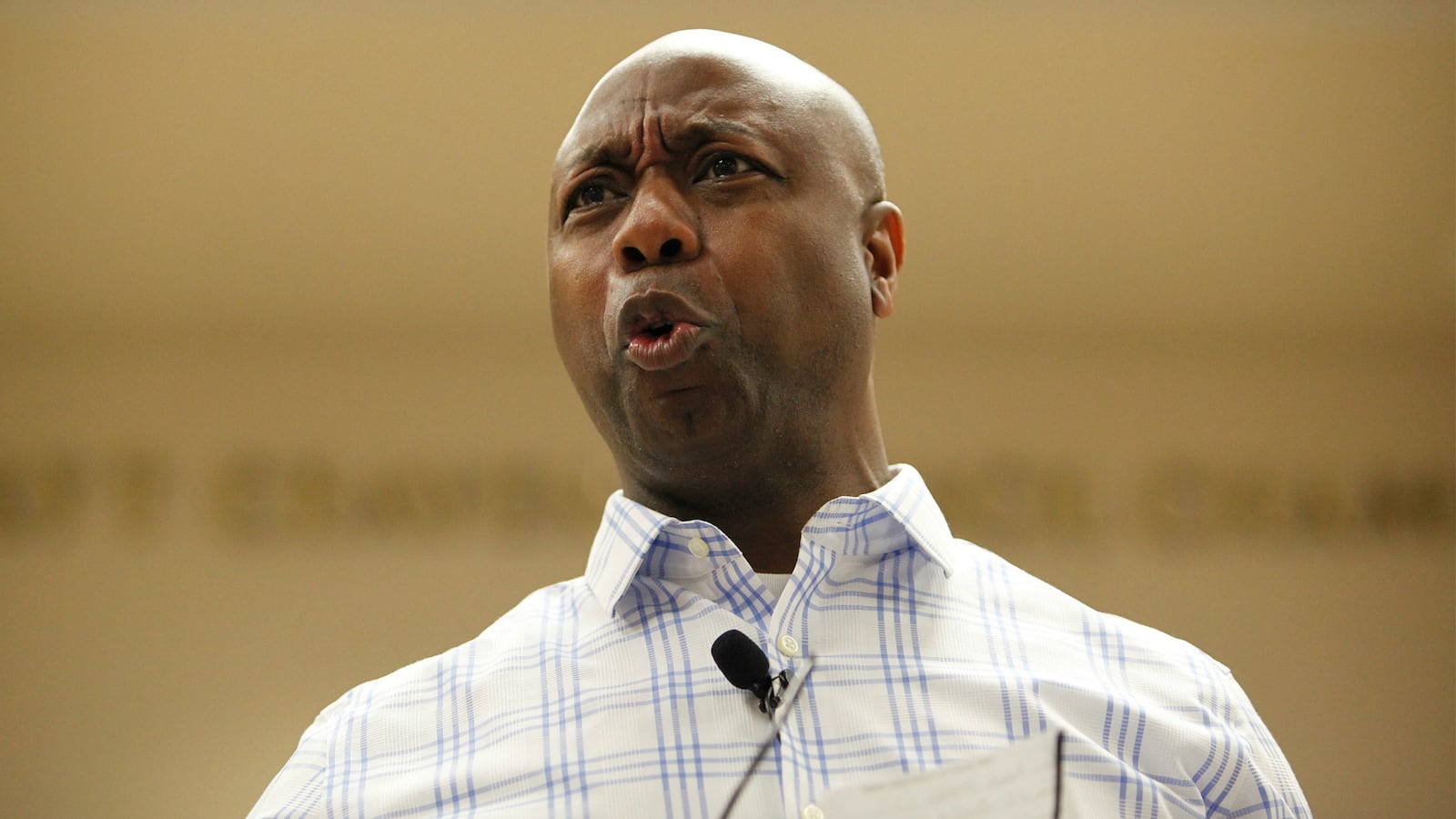

According to a GOP source familiar with the matter, Scott, the only black Republican senator, raised concerns to Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) about Ryan Bounds’ college writings which allegedly included racially charged comments and other controversial statements.

Rubio, the source said, pledged to vote against Bounds alongside Scott, and “more Republicans [were] heading to ‘no’” on the nomination as a result.

McConnell then withdrew the nomination—but not before huddling with his top deputy, Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn (R-TX), in his office off the Senate floor. The saga unfolded just minutes before the scheduled 1:45 p.m. vote. By 2:30 p.m., it was over.

The majority leader’s decision to withdraw the nomination comes as the Republican majority has confirmed a record number of judicial nominees in the first 18 months of Donald Trump’s presidency. Bounds was nominated to serve on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Bounds’ nomination was so toxic that his two home-state senators—Democrats Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden, who opposed his appointment—tried to use Senate procedures to kill the nomination. Those efforts were rebuffed by Republicans.

Bounds, who attended Stanford University for his undergraduate studies, was accused of failing to disclose his writings in The Stanford Review to a bipartisan committee of attorneys that initially recommended him for the post.

During his May confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Bounds apologized for those articles, which he called “overheated, over-broad and too often not as respectful as it should have been of opposing viewpoints.”

“I certainly apologize for the often highhanded and overheated tone I often resorted to in commenting about campus politic,” he told the committee. “The intentions behind those articles were always to seek greater tolerance and mutual understanding on campus—that was always my aim.”

The writings, compiled in a briefing by the Alliance for Justice, tell a different story.

In October 1994, Bounds argued against lowering the burden of proof for students accused of sexual assault.

“There is really nothing inherently wrong with the University failing to punish an alleged rapist—regardless of his guilt—in the absence of adequate certainty, there is nothing the University can do to objectively ensure the rapist does not strike again,” he wrote. “Expelling students is probably not going to contribute a great deal toward a rape victim’s recovery; there is no moral imperative to risk egregious error in doing so.”

Another article in February 1995 took aim at “multiculturalists” who “band together not into tight cliques of mutual interests and complementary powers, but rather into social clubs of ostensibly common racial heritage.”

A third, an October 1994 article titled “Lo! A Pestilence Stalks Us,” railed against the “sensitivity” of LGBTQ student reactions to the vandalism of a “gay pride” statue. He also criticized the reactions of Latino students who protested after the lone “high-ranking Chicano” administrator was “terminated.”

“Results: rivers of tears, epithets, hunger strikes, negative press for the university, and the formation of presidential committees to examine the ‘systemic insensitivity’ toward Chicanos at Stanford and the potential for a Stanford-East Palo Alto community outreach center,” he wrote. “Oh, and once again, sensitivity can claim responsibility for extortion, rampant dissatisfaction, and a nice week of hand-wringing.”

Bounds currently serves as an assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Oregon.