Shortly before 11 p.m. on Aug. 17, 2010, Teaneck, New Jersey, resident Angela Bombardi smelled something burning. She checked to make sure it wasn’t coming from her own home, then stepped outside to have a look. That’s when Bombardi realized the tidy Tudor-style house directly next door was on fire and she called 911.

Firefighters were eventually able to beat back the blaze, which had started in a first-floor bedroom. But when they discovered the badly charred remains of 74-year-old Joan Davis inside, it soon became apparent that the fire had been set intentionally—in an attempt to cover up a murder. Davis was burned beyond the point of recognition and authorities had to use dental records to identify her. Before being set alight, Davis, who lived alone and didn’t have many friends, had been bludgeoned, bound, and stabbed numerous times.

Bergen County Prosecutor John Molinelli, whose office formed Bergen’s first dedicated cold case unit in 2002, helped lead the investigation.

“I remember the case very well,” Molinelli, who left government service for the private sector in 2013, told The Daily Beast. “I was at the crime scene. I was in the house. I saw Ms. Davis, regrettably.”

The charred interior of Joan Davis’ home on Alpine Drive.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeDavis was a “very secretive, protective person,” Molinelli continued. “She guarded her privacy zealously. There were many, many locks on her door, that were all locked… [A]t least three, maybe four. That kind of told us that whoever murdered Ms. Davis knew her, or at least was [allowed into] her place. We never thought that whoever killed her forcibly gained entry.”

The quiet township of Teaneck sits roughly 13 miles from Manhattan, and was once home to squeaky-clean singer Pat Boone. Families, many of whom commute to work in New York City, “look to Teaneck to provide comfort, peace, and the best in educational recreational facilities for their children,” the U.S. Army said in 1949, after selecting the North Jersey burg of 40,000 to represent a model community upon which occupied countries such as Japan and Germany might base their postwar rebuilding efforts.

No one in Teaneck knew much about Davis, who moved to the neighborhood around 1990. She didn’t have a job, had no children, and was almost completely estranged from her only sister, Mary, who occasionally helped Davis pay her bills.

In the late 1960s, Davis worked for USAID for a couple of years and was stationed in Rio de Janeiro. There, she met and fell in love with a married man named David Davies, eventually changing her surname from Curello to Davis. A few years later, Davis moved back to the U.S. Davies also returned to the States and established his own life in New Jersey and then the Midwest, working as a progressive activist and eventually getting into politics. Davis’ nephew, Peter Bonadies, said he had no idea why his aunt took Davies’ name—slightly misspelled—without ever having married him. Davies died in 2020. No one ever learned much more about their relationship, said Bonadies.

Bonadies, a sculpture teacher in Connecticut with three kids of his own, was never exactly sure why Davis moved to New Jersey from Connecticut, where she grew up and where her relatives, including Bonadies, still lived. Whatever the reason, when Davis got to Teaneck, she became extremely outspoken about local politics.

She was an early advocate for progressive policy positions and social justice, and regularly sent letters to Teaneck officials with her opinions on how the municipality could be better managed. She also showed up at every town meeting she could, using her allotted five minutes to tell the mayor and others what they were doing wrong.

“She was a ‘community activist,’ for lack of a better word,” Teaneck Deputy Mayor Elie Katz told The Daily Beast, adding that he thought there was something “not 100 percent right” about Davis’ mental state. “Joan Davis wouldn’t hurt physically, a fly. Was she annoying to many? Absolutely. I hate to use the word ‘sweet,’ because sometimes she really pissed you off… But she really was an innocent person, even if she irritated you.”

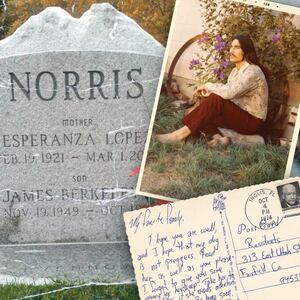

Joan Davis in happier times.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeThe minutes from a June 2008 meeting of the Teaneck Township Council sum up the things on Davis’ mind at that time.

“Ms. Davis is concerned about the environment and is shocked by all the damages [sic] of trees,” the minutes state. “The Township should redirect its efforts from businesses to the environment; do things as a community to cut gas consumption.”

That September, Davis appeared at another council meeting to confront Teaneck’s leaders about why the township was sharing a defibrillator with nearby Holy Name Hospital, why Teaneck was “bidding out trees for so much money,” and why road resurfacing contracts all seemed to be going to a certain bidder.

A decade earlier, Davis wrote to the alumni magazine published by her alma mater, the University of Massachusetts. She said she was “disappointed” that the pages were filled with the accomplishments of white people, “with the result of missing the hopefully growing presence of blacks and other minorities in UMass history.”

“If the magazine is to be an editorial opportunity for white self-congratulation, then take my name off the mailing list,” Davis wrote. “There is enough white-centered public acceptance in journals. If the magazine is to become a voice to balance much-needed honor to the past while encouraging the present multi-cultural population to excel in their chosen professional fields, then count me in. I look forward to seeing youthful, clearly black faces, not the elders of the community or the coaches of winning athletic teams who are periodically honored by other press instruments.”

There was “some sort of paranoia” present in Davis’ mind that was never formally diagnosed, said a relative who declined to be identified for fear of causing familial strife. It started around the time Davis got back from her government posting in Brazil, and Davis thought that “someone was going to do her harm, that she had some information from her job at USAID and that people were out to get her,” including her sister “who was just so loving to her.”

When Bonadies had his tonsils out at age 19, Davis showed up to visit him as he recovered. While she was there, Davis went on and on about how her sister—Bonadies’ mother, Mary—was supposedly sabotaging her life. Bonadies, now 48, told The Daily Beast that he finally reached his limit and began to distance himself from Davis.

They talked “a couple of other times after that,” according to Bonadies, who said he spoke to Davis for the last time around 1998.

Twelve years passed without a word. In November 2009, Mary Bonadies died following a long battle with progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare brain disorder. She was 75. Shortly before she succumbed, Bonadies and his sister were visiting their parents at home. Mary’s health was really failing at this point, and Bonadies remembers asking the others, “Do you think we should call Aunt Joan and just have mom hear her voice before she passes?”

“We decided not to—we didn’t want dad to experience any more pain than he had to [with her] bringing up all this stuff from the past,” said Bonadies. “Who knows what would’ve been said. So mom passed, and I don’t recall if I ever reached out to her to tell her.”

Ten months later, Davis was dead.

“It was just so eerie, her death, because for years she talked about people that were after her, and that someone was going to get her,” said Bonadies. “And then this brutal murder takes place.”

A hammer was among the evidence detectives found inside.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeBonadies and his wife headed to Teaneck from Connecticut a few days after Davis’ death. They arranged a funeral service, and although Davis’ wish was that her body be donated to science, the corpse was too badly burned. So Bonadies had Davis’ remains cremated, and waited for detectives to arrest the person who murdered his aunt. The whole family wondered why Davis had been selected by her killer, and were frightened that they could be next.

Elie Katz said he was both “shocked” and “saddened” by Davis’ death.

“When someone gets stabbed 30-something times, that’s someone who is very, very angry,” said Katz. “A couple of times should’ve done the trick.”

John Molinelli, Bergen’s then-head prosecutor, said he met with Teaneck’s then-mayor as well as a state senator who knew Davis and “wanted to impress upon me the need to devote whatever resources were necessary to close this homicide.”

“Unfortunately, through social media and television and movies, criminals learned a long time ago that when they light the crime scene up with a fire, it makes the job of the forensic examiner a lot more difficult,” Molinelli said.

Davis’ burned-out home after the fire.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeStill, investigators did find one potentially useful clue in the kitchen. After setting the fire, whoever killed Davis escaped through a window in the kitchen, and left a shoeprint in the sink below.

Police believed the print was made by a size 9 or 10 sneaker. However, it was such a common brand—in crime scene photos, the tread appears to be that of a Nike Air Jordan of that era—that it wasn’t particularly useful to detectives.

Roughly five months prior, 69-year-old Delores Alliotts was found stabbed to death inside her home in Palisades Park, about five miles from Teaneck. As in the Davis case, Alliotts’ home had also been set on fire in an attempt to destroy evidence, according to cops. And like Davis, Alliotts lived alone.

The community was on edge, wondering if there was a serial killer on the loose.

Investigators dug into the lives of both women, trying to figure out if their killings were connected. Where did they do their grocery shopping? Who picked up their garbage? Were they members of the same clubs? Molinelli said detectives thought there was a “strong probability” that the same person who killed Davis was also behind Alliotts’ murder.

Yet, they never had a match and both cases soon went cold. The fact that Davis didn’t have a real social circle, and few people interacted closely with her, made the investigation much more difficult. Authorities have never publicly identified a suspect in either case.

A shoeprint left at the scene.

Bergen County Prosecutor's Office“It was so very sad for us—the only closure I feel is that she is with my mom, grandma and grandpa with no illness or fear,” Davis’ niece, Susan, who lives in Virginia, told The Daily Beast in an email. “God rest her soul.”

After Davis died, Bonadies kept in touch with Bergen County detectives, calling every couple of months. Eventually, without ever getting any news from investigators, the calls became less and less frequent. Once people working his aunt’s case began to retire, “no one knew anything and I just stopped calling,” Bonadies said.

“We’re still spooked,” he continued. “It was a brutal murder. We’re scared, still.”

In most instances, investigations tend to slow down about 60 days after a crime is committed, said Molinelli: “At that point in time, it becomes more and more difficult to find new things.”

But, he added, “Cold cases are never really ‘reopened’ because they’re never really closed.”

In August, nearly 21 years after Davis’ death, the Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office announced that its detectives would be revisiting the Davis case. For the first time, investigators released surveillance video that shows a person of interest walking in the direction of Davis’ home about 50 minutes before she was killed, and walking back away from the area just shy of two hours after Davis was stabbed to death.

“We have started releasing cold case videos on our website and social media every month in an effort to bring attention to these investigations, which are important to us and to the victims’ families,” Elizabeth R. Rebein of the Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office told The Daily Beast.

Molinelli believes the Davis murder is solvable, pointing to New Jersey serial killer Richard Cottingham, who was caught three decades after his alleged killing spree. Cold case detectives generally start fresh and reinvestigate from square one, rather than reviewing what investigators did previously and trying to poke holes in their work.

To begin, witnesses will be re-interviewed, said Molinelli. If someone can’t be found, is there a reason why? Detectives will review prison records, arrest records, and crosscheck intelligence databases for other crimes with similar characteristics in New Jersey and beyond. DNA samples from the crime scene, if any still exist, can be tested using new technology that wasn’t around in 2010.

Detectives released footage of a person of interest for the first time in August 2021.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeMedia coverage never hurts either.

“You never know when somebody reads something and remembers something and decides to come forward,” Molinelli said. “No one likes to have any homicide go unsolved, because you owe it to the victim and you owe it to the victim’s family. They always say, ‘We want closure.’ There's never closure for the family. But when justice is done, it at least gives them peace.”

This is the main reason why Katz made himself available for interviews with reporters after Bergen detectives recently released the new clues about Davis’ possible killer.

“Hopefully with this new evidence, they’ll be able to track down the person who did it, or the people behind that person,” said Katz, offering a theory that someone who wanted Davis dead hired the killer to do her in. “My allegation—I have absolutely no facts to base it on, just my personal feeling—is that this seemed like a crime of passion.”

The kitchen window through which investigators think Davis’ killer fled.

Bergen County Prosecutor's OfficeDavis’ boarded-up home was sold to a real estate investor in 2019, and renovations began over the past seven months or so, according to Katz. Some of the newcomers who live nearby had no idea what happened that night in August 2010 at 976 Alpine Drive. But Molinelli, for one, will never forget.

“You know, she kept public officials on their toes,” Molinelli said. “Every town should have a Joan Davis.”