Walking from the subway to Beyond the Streets, a new graffiti and street art exhibit in Williamsburg, serves as a pregame for the main exhibit.

Nearly every block on a stretch of Wythe Avenue includes a bright mural advertising companies like Madewell, J.Crew, and Adult Swim. Just this week, a few blocks away, Kendall Jenner debuted a new Proactive ad painted on the side of a brick building.

It wasn't always like this. In 1972, New York’s Mayor John Lindsay declared a “war on graffiti,” devoting 10 million of the city's dollars to scrubbing scrawl off of subway cars.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s a dirty shame we must spend money for this purpose in a time of austerity,” Lindsey said.

One 1970s ad endorsed by Philadelphia's Olney Community Council bluntly put it: “Graffetti [sp] writers are mean and cruel and have no respect for themselves or others.”

Beyond the Streets, which debuted in Los Angeles last year, tows a tricky line. The exhibit celebrates the rebellious origins of graffiti in American cities, while acknowledging the eventual gentrification of the art form.

“These artists grew up hopping fences, going places you shouldn’t go late at night,” Roger Gastman, lead curator of the exhibit, told The Daily Beast. “We wanted to take artists who worked on the street but went on to have a great studio career, and see where their works are today.”

The massive exhibit takes up two floors inside of an office building high rise. The setting feels a bit incongruous to its subject matter, but at least the floor plan provides ample room to graze past over 150 pieces.

You will not find salvaged walls covered in spray paint, or scratchiti—carved words in subway seats and the like—taken from an A train on display. Though Beyond the Streets tells a bit of history, the pieces on display were made and intended to be shown in galleries.

At the exhibit’s press opening this week, the actress Rosie Perez gave opening remarks. (Please note: this is how all events should begin.) Wearing a Biggie Smalls sweatshirt and a megawatt smile, the Brooklyn native spoke of her admiration for graffiti writers—including her husband, the artist Eric Haze, who has designed logos for Public Enemy, the Beastie Boys, and LL Cool J.

“They all thought [graffiti] was going to be a passing phase, and it hasn’t been,” Perez said. “It’s been a cultural phenomenon, and I never dared to tag my name up there because I was corny and I was afraid to get arrested.”

One early tagger, Mike 171, stood proudly by his work (always at arm’s length from Wall Writers, a coffee table book based on a 2016 documentary film Gastman directed).

Now 63, Mike 171 began tagging at age 12. He showed up to the gallery opening in a jacket with “Graffiti at its innocence” blazed on the back.

“We started in 1968,” Mike 171 recalled. “We wrote with shoe polish, because we didn’t know about markers and paints.”

It was a time of political and personal tumult for the preteen, whose father died in 1968. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, and the Vietnam War raged on overseas. “I took to the streets, and the streets became my family,” Mike 171 said.

The burgeoning form of expression may have brought some comfort, but it was still illegal. A family connection kept Mike 171 mostly out of trouble.

“My mom worked in a bar where all the cops went,” he said. “They gave me a lot of play to do what I had to do. They’d kick me in the ass, smack my in the head, say, ‘Mike, get the fuck out of here,’ blah, blah, blah.’”

“I got away with a lot,” he remembered. “I never got a big time arrest.”

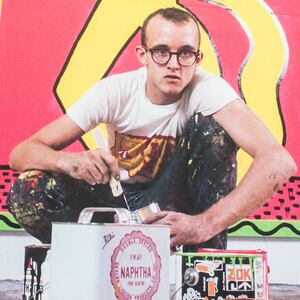

‘Mike 171.’

Daniel BradicaThe small wing where Mike 171 staked his claim during the exhibit’s opening offers a light history lesson. Museum placards describe the emergence of graffiti in New York and Philadelphia in the late 60s. It began both as a means for gangs to claim territory and for teenagers to flex their bravado, trying to spray paint their bubble letters on walls, trains, and buses across their city.

Many of their original work has been lost to time—or a pressure washer—so these artists are represented through reproductions and film photography from the era documenting their exploits.

One city payphone, salvaged from the '70s, is been scratched with the words “PRAY.” In the late '60s, that four-letter word began popping on phone booths. No one knew the culprit.

In 1992, the artist Tracy 168 revealed PRAY’s identity—sort of. Tracy 168 told the New York Times that he once saw an elderly woman leaving the mark around a subway station, and that he stopped to hold up a magazine to keep her actions discreet.

Upstairs, the contemporary street artist Shepard Fairey has a mini collection of new work, including retakes on his popular 2008 “Hope” stencil portrait of then-presidential nominee Barack Obama.

‘Shepard Fairey.’

Daniel BradicaMore than a decade later, his pop art sensibility remains. But much has happened since 2008. “Hope” has given way to works like “Defend Dignity,” a portrait of the activist Maribel Valdez Gonzalez that was carried at various anti-Trump protests in 2017.

Near Fairey's section is a sampling of protest art, including posters by Emory Douglas, a former Minister of Culture and in-house artist to the Black Panther Party.

Douglas began branding for the militant movement in 1967. His work, which often portrayed police as pigs and frequently extolled “all power to all people,” earned him many threats. As mentioned in the exhibit, one anonymous letter warned Douglas that the writer would cut his hands off, so he could no longer draw.

The Guerrilla Girls, the well-known collective of female artists combating sexism and racism in the art world, are also on display. The group formed in 1985, and most of their posters shown are from that era. But the sentiment still runs frustratingly true.

‘Guerrilla Girls.’

Daniel BradicaOne graphic reads, “The definition of a hypocrite is an art collector who buys white male art at benefit for liberal causes, but never buys art by women or artists of color.”

In order to view these often anti-capitalist pieces, one must first pass by a gift shop and Perrier station. The mineral water company helped sponsor Beyond the Streets along with Adidas.

“Fifty-one years later, and here we are,” Mike 172 said. “We're the pioneers. Once the first painting was sold, it became commercial. [That] took the innocence and purity out of what we're doing.”