What novels and story collections has our paper of record overlooked this year? The question seems especially pertinent with The New York Times’s recent 100 Notable Books in holiday shoppers’ minds. There are some 40 fiction titles on that list—a healthy mix of bestsellers, literary lions, and fresh-faced rookies. Does it cover the bases? To find out, I stacked up 10 works of fiction published within the last six months that the Times has failed to review. If I wasn’t hooked by page 50 or so, I set the book aside. Six books hit that discard pile; four were absolutely first-rate. And here they are—a list for the underdog champion in all of us, two novels and two short-story collections as well written, immersive, and satisfying as anything I’ve read this year.

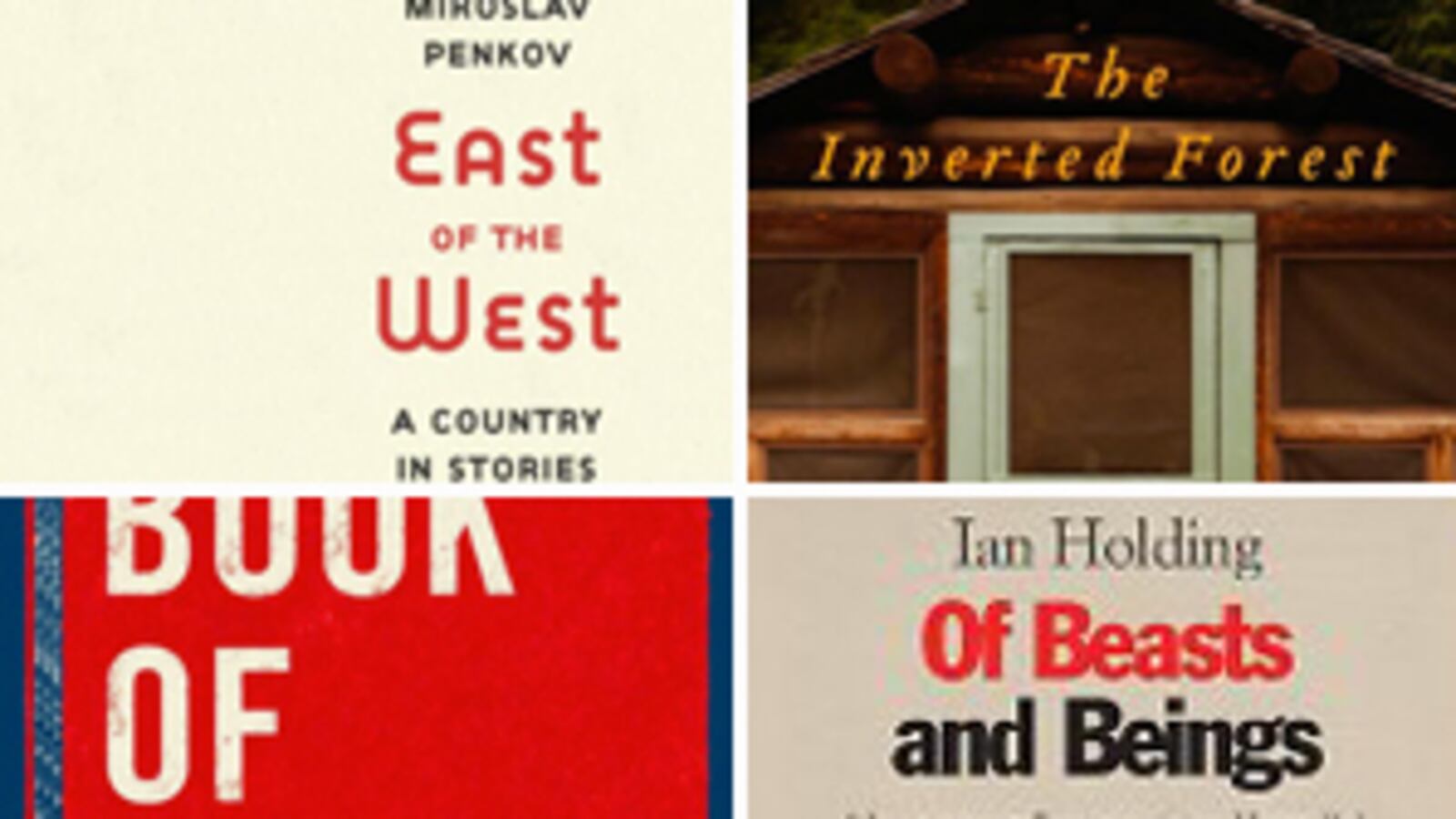

The Inverted ForestBy John Dalton

John Dalton’s masterly, deeply humane second novel offers old-fashioned Updikean pleasures: emotionally complex characters, gorgeously tuned sentences, and a briskly paced plot. We’re at a Missouri sleep-away camp in the summer of 1996, and the straitlaced camp owner has impulsively fired his entire staff of counselors for a nighttime episode of drunken skinny dipping. He repopulates on short notice but tells none of his new hires that during the first week of their summer they'll be responsible for a group of severely disabled adult campers. Dalton handles these men and women—wards of the state, unable to care for themselves in even the most rudimentary ways—with astonishing deftness, lending them a wholeness and dignity even as he communicates how disquieting their appearance and chaotic behavior can be. Suspense is generated as two counselors, a swaggeringly confident lifeguard and a young man who bears a physical disfigurement of his own, proceed along a collision course. A well-meaning action by the camp nurse, Harriet Foster, Dalton's most empathetic creation, precipitates an act of violence with piercingly sad consequences. This is among the best and most affecting novels of the year, an astonishing miss by the book editors at The New York Times.

Of Beasts and BeingsBy Ian Holding

The dystopian novels keep piling up (Zone One and The Leftovers are only the two most recent to hit your local bookstore), but Zimbabwean novelist Ian Holding’s harrowing and provocative vision of a ravaged, apocalyptic African landscape is especially worthy of notice. Handsomely bound in paperback by Europa Editions’ new Tonga Books imprint, which publishes manuscripts selected by prominent contemporary writers (Alice Sebold shepherded Of Beasts and Beings into print), it follows two seemingly disparate narratives, that of a nameless starving figure enslaved by a ragtag band and, in a more recognizable present, that of a white teacher in his 30s, who has wearied of Zimbabwe’s climate of corruption and violence. The former, relentlessly bleak sections are written in a rhythmic, arrestingly connotative style, reminiscent of the hallucinatory lyricism of Michael Ondaatje or Chris Abani. The teacher sections are much more plain-spoken and seem to come from a different novel altogether—until Holding’s thoughtful conclusion, which ties both strands together in a genuinely surprising way. The novel is challengingly bleak (Tonga Books has taken as its mission to champion dark material), but it resonates with complex ideas about the wages of oppression, racial guilt, and psychological isolation.

The Book of LifeBy Stuart Nadler

One thing becomes readily clear about Stuart Nadler, whose graceful, keenly perceptive debut collection offers narratives of young love, middle-class infidelity, families in mourning, and fathers connecting clumsily with sons: this guy has read his Cheever. The comparison lives in Nadler’s subject matter, of course, but it’s also in his setting—New England, chiefly Boston—and in the lovely Puritan clarity of his prose. The fact that this Iowa M.F.A. graduate’s characters are almost all Jewish only makes the comparison more interesting. (Who is our Jewish Cheever, anyway?) A proviso: I stubbed my toe on the first story, which was published in The Atlantic and concerns a businessman’s fling with his partner’s young daughter; its plot machinations felt forced, Nadler’s prose lead-footed. Happily, the stories that follow it more than carry the collection. “Winter on the Sawtooth” is an especially stunning and generous piece of work—a portrait of a father struggling to overcome a betrayal by his wife and an estrangement from his son. “The Moon Landing” gets the heated confusion of siblings mourning dead parents precisely right. And “Visiting”—about a father-son road trip to Narragansett, R.I.—is a prickly minuet of paternal longing. Nadler’s work celebrates the complexity hidden in ordinary-seeming lives and makes you eager to read whatever he writes next.

East of the WestBy Miroslav Penkov

This witty, warmly off-kilter debut is a portrait-in-stories of Bulgaria—a country not much seen in the pages of contemporary American fiction. But 30-year-old Penkov, who moved to the U.S. in 2001 and who writes in English, is a rewarding literary tour guide. The lead-off story, “Makedonija,” reads like Alice Munro transported to Sofia: an elderly Bulgarian in a nursing home is swept away by his ailing wife’s love letters from a soldier fighting the Turks in 1905. “East of the West” starts with the sunny tone of a folktale—two cousins falling in love across the border between Bulgaria and Serbia—before darkening with the troubled politics of the region. The narrator’s sister is shot trying to flee communist Bulgaria, and the two lovers are separated by war. Sad material, but Penkov keeps his deadpan humor: “The good thing about our countries,” his narrator says after bribing a Serbian soldier, “is that if you can’t buy something with money, you can buy it with a lot of money.” Other stories capture the dislocation of a Bulgarian returning to his home country with a foreign wife and the madcap adventures of school-age protocapitalists in Sofia. Penkov’s prose has a lovely, syncopated lyricism, a style reminiscent of Aleksandar Hemon (another Eastern European transplant). East of the West seems to have been unanimously praised but not widely reviewed—which is a shame. This is a distinctive new voice worth savoring.