Asheville, a city of 95,000 nestled in the verdant foothills of North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, is well-known as a bastion of funky Southern charm. It is home to dozens of breweries, a thriving music and arts scene, and one of the most architecturally intact historic downtowns in the nation. It is also the unexpected final resting place of Rafael Guastavino, once one of the country’s most celebrated and innovative builders, whose name and architectural influence have since been largely forgotten.

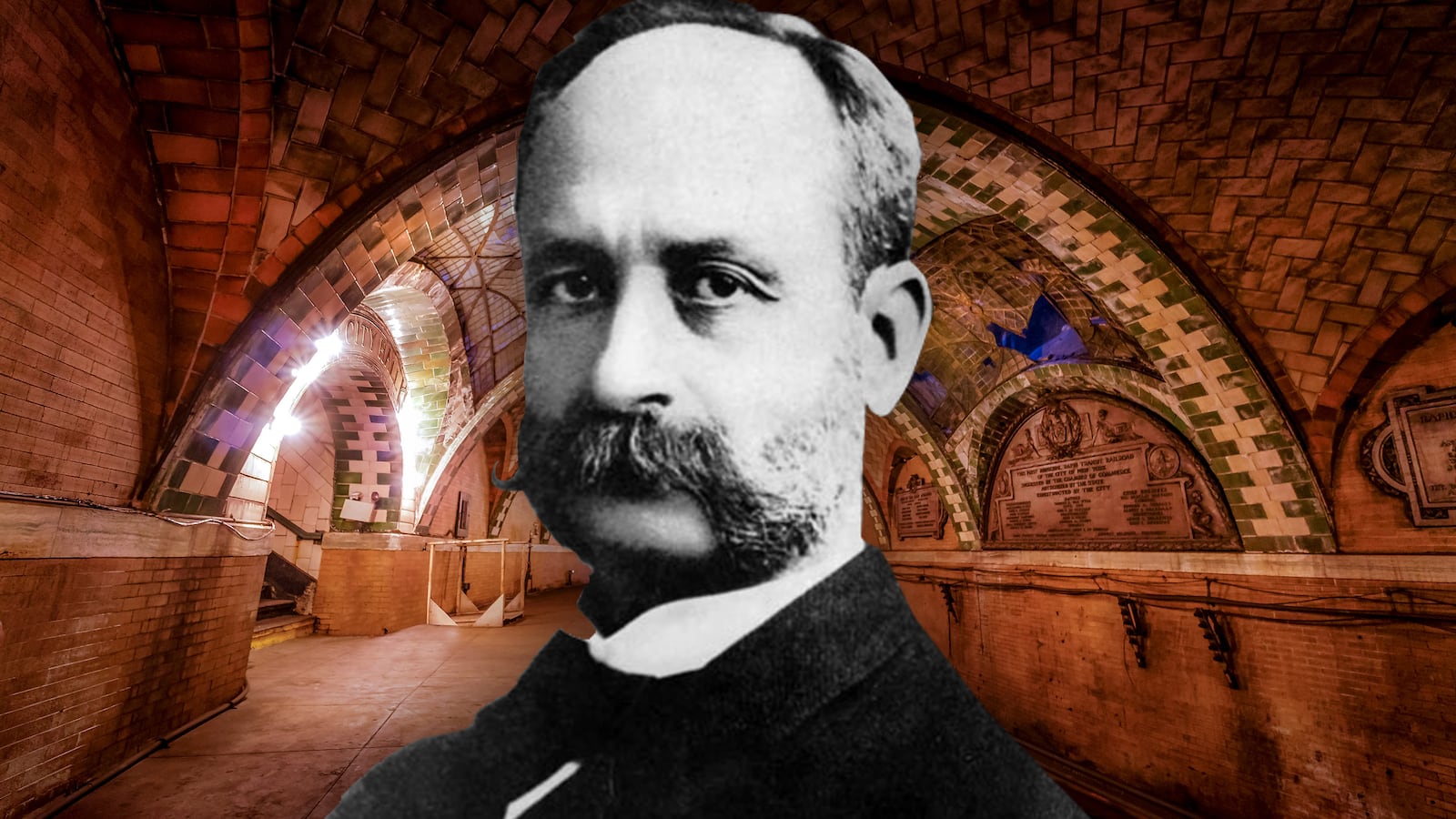

Born in Spain in 1842, Guastavino immigrated to the United States in 1881. In New York, he ingratiated himself with the nation’s leading architectural firms and their wealthy clients. His signature work was a style of elaborate tile vaulting, common in his Spanish homeland, using lightweight clay bricks to create lofty, open interior spaces without the need for heavier, more expensive materials. The “Guastavino Method” allowed architects to not only save money but to create larger, lighter spaces than otherwise possible.

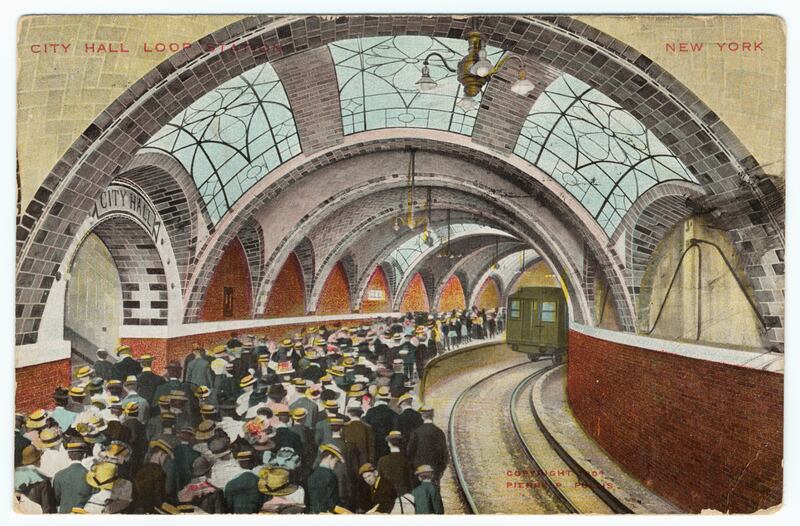

Illustrated postcard of passengers waiting for the train below the the vaulted ceiling of the City Hall subway station, a.k.a, 1904. City Hall Loop, Manhattan, New York City.

Smith Collection/Gado/GettyGuastavino is best known for his landmark projects in New York and Boston. His revolutionary tile vaulting system can be found in the Boston Public Library, the Plaza Hotel, and the New York City Subway. His construction firm, which remained in business until 1962, employed the “Guastavino Method” in hundreds of other buildings across the nation, including the capitols of Massachusetts, Louisiana, West Virginia, and Nebraska.

As his reputation grew, so did Guastavino’s star-studded client list. In addition to grand public works, he was enlisted to vault the homes of families such as the Morgans and the Vanderbilts. His work can still be seen at the Breakers, the palatial summer home of Cornelius Vanderbilt II in Newport, Rhode Island. But it was Cornelius’s younger brother, George, who invited Guastavino to North Carolina in 1890. There, he had already spent years building his “summer getaway home,” a sprawling chateau called Biltmore. With nearly 180,000 square feet of floor space, it remains the largest private home ever built in the United States.

George Washington Vanderbilt II was the youngest of William Henry Vanderbilt’s eight children. His older siblings, leaders of New York’s social scene, married into other wealthy families and established a colony of grand mansions along Fifth Avenue, which came to be known as Vanderbilt Row. George, however, floated between residences, seemingly uninterested in the trappings afforded him by his name and inheritance. It wasn’t until he began traveling with his mother to western North Carolina that he found a place he wanted to call home.

The Biltmore Estate, the largest privately owned home in America, built by George Vanderbilt between 1889 and 1895, is one of area's major tourist draws.

George Rose/GettyConstruction on the Biltmore began in 1889, transforming 125,000 acres of hilly farmland into an estate reminiscent of France’s Loire Valley. Richard Morris Hunt, the man behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s great entry hall, modeled the home after several chateaux including Blois and Chantilly in France as well as Waddesdon Manor in England. Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, was responsible for the estate’s manicured grounds. George Vanderbilt was a quasi-renaissance man, deeply appreciative of arts and letters. He surrounded himself not with fellow heirs and socialites, but with writers, painters, and all manner of creative types. Portraits often depict him holding a book, his finger cleaving its pages as if he’s been interrupted mid-sentence.

It was George’s creative appreciation which brought Rafael Guastavino to Asheville. There, he was asked to install his famous Spanish vaults at the Biltmore Estate. His iconic striped tiles, arranged in an elegant zigzag pattern, can be found in the mansion’s entry hall, above its underground swimming pool, and all around its glass-enclosed winter garden. Guests even pass beneath a grand arch of Guastavino tiles inside the Biltmore’s gatehouse. His work added flair and a touch of industrial whimsy to a house which was otherwise built as an American homage to traditional French châteaux.

On a recent tour of the Biltmore, led by the estate’s curator of interpretation, Leslie Klingner, I saw firsthand the beauty of Guastavino’s work. Here, Leslie explained, his vaults aren’t structural. They were installed specifically for aesthetic purposes, adding a modern, geometric flair to many of the house’s most prominent spaces. George Vanderbilt saw Guastavino’s tiles as being intrinsically valuable, beautiful enough to grace his home as architectural works of art.

While working on the Biltmore, Guastavino fell in love with the surrounding landscape. He lived on the mansion’s grounds during construction, and built his own estate just east of Asheville, in the town of Black Mountain. Rhododendron, as he called it, encompassed more than 600 acres of forested peaks and valleys. The main house was a three-story wooden pile with a bell tower which the locals called the Spanish Castle. There, Guastavino enjoyed a quiet but busy life, overseeing building projects, bottling his own cider, and even planting a wine-producing vineyard. He built kilns where he experimented with firing bricks and tiles to be used in his many commissions. The estate was razed in the 1940s following the death of Guastavino’s widow. The land is now home to “Christmount,” a religious retreat and conference center.

The final, and perhaps most significant project executed by Guastavino in North Carolina would come to serve as his tomb. A devout Catholic, he lamented Asheville’s lack of a suitable church. He donated heavily to local efforts to build a Catholic cathedral and was its chief designer when construction began in 1905. That church, now known as the Basilica of St. Lawrence, boasts an enormous elliptical dome unlike any other church in the country, or even the world. Fifty-eight by 82 feet in diameter, the dome is made of Guastavino’s signature tiles in shades of pale sandy pink. Despite its immensity, it appears to float above the nave. “This mighty vault,” described the Asheville Citizen-Times in 1909, “was built bit by bit over nothing, above the church floor.”

Interior of the Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville, North Carolina.

GettyThere, beneath the dome he designed, Rafael Guastavino was interred following his death in 1908, at age 55. His obituary called him “an authority on new methods of construction,” but his achievements far surpassed that. Guastavino was an innovator and an artist, and the influence of his work long outlived him. His son, Rafael Guastavino Jr., took over as head of the Guastavino “Fire-Proof Construction” Company. Under his leadership, using his father’s methods, Guastavino tiles were installed in more than a thousand projects nationwide.

The younger Rafael completed many of the firm’s most iconic and enduring projects. He was responsible for the new barrel-vaulted ceiling in the great hall of Ellis Island as well as what’s now the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal. He vaulted the underside of the entry ramps for the mighty Queensboro Bridge; a portion of that airy space now houses a restaurant called “Guastavino’s.” Describing the space as it was being prepared for adaptive reuse in 1973, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable called it “a dramatic series of cathedral-like vaults and arched openings of landmark quality.”

When the Guastavino company shuttered in 1962, its archives were donated to Columbia University. More than a century after the elder Guastavino’s death, his influence and designs can be found seemingly everywhere. Particularly in New York, residents might pass half a dozen Guastavino vaults in their daily comings and goings. But it was far from the city’s crowded streets and terminals, in the forested quiet of North Carolina, that Rafael Guastavino chose to live out his final years and execute his final projects. There in Asheville, the man who so changed the urban landscape rests peacefully beneath a dome of his own design.