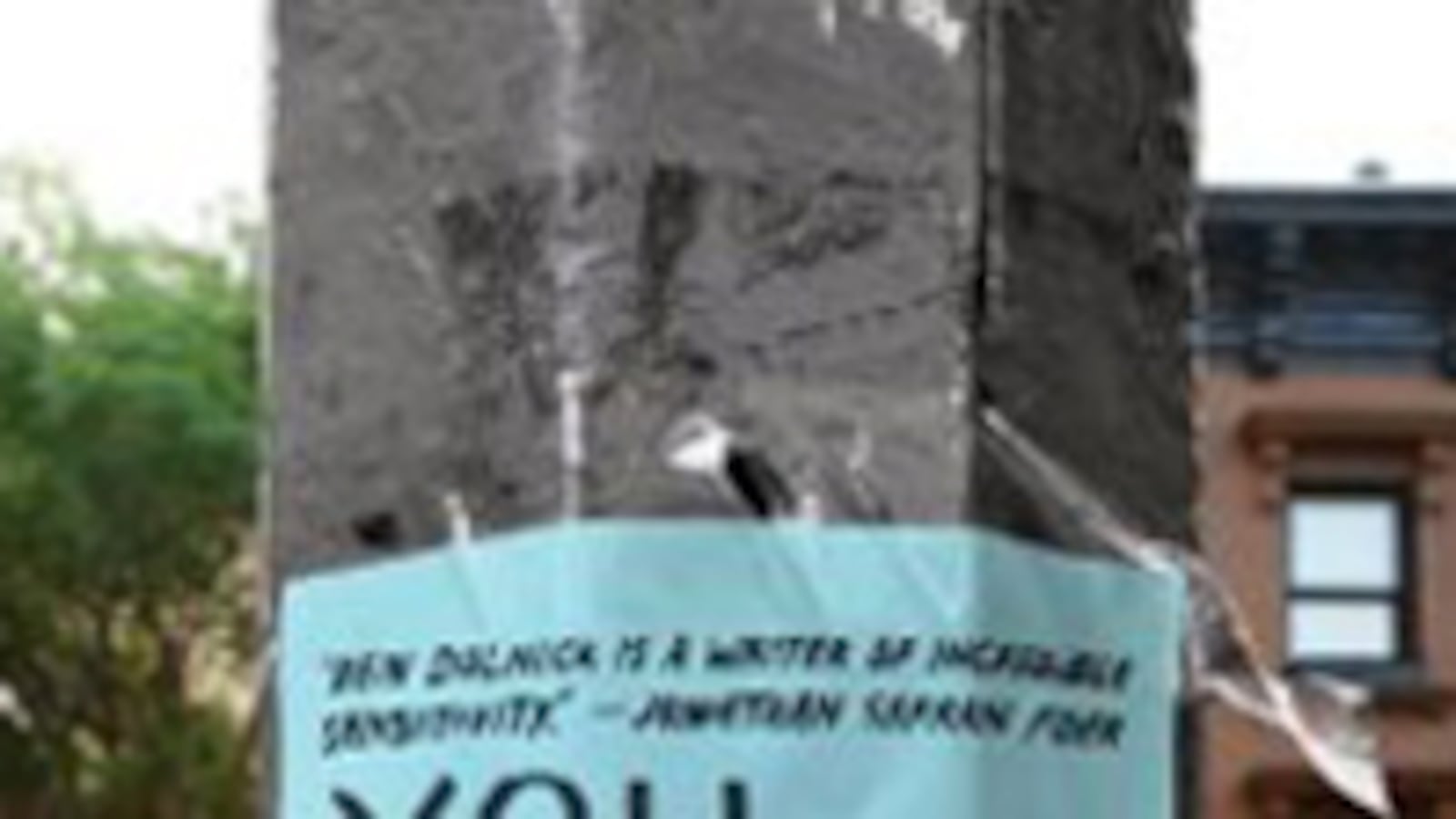

You Know Who You Are

There is a brave kind of confidence required to tell a simple story, with no po-mo trickery or grand melodrama, and young author Ben Dolnick has already found that confidence in spades. In Dolnick’s second novel, You Know Who You Are, he shows considerable skill in creating rich and resonant inner lives for his deeply imagined characters, without a reliance on anything other than honest reporting on the events of a fairly regular life. Eschewing the ironic mantle of his generation, he has created a captivating human portrait, and promises to be a strong force in the fight to reclaim earnestness.

The plot of You Know Who You Are is not the kind of thing that makes for great dust-jacket copy. The book follows 15 years in the life of the Vine family, as seen from the vantage point of middle child Jacob. Opening with one of Jacob’s first childhood traumas, namely his older brother Will informing him that he no longer wants to share a room, it ends 15 years later, with Jacob fresh out of college and the brothers in another dispute, this time over a woman. In between, we seamlessly follow Jacob’s life as he suffers through the social politics of his grade school classroom, awkward incidents of his sexual awakening, and fumbling attempts at love. As he slowly decides that what he is experiencing actually constitutes his life, and that he is tenuously OK with that, we realize that we have witnessed the growth of a child into an adult the way it happens in real life; gradually, without a watershed “coming of age” moment.

Perhaps the best sections are the early ones, in which Dolnick shows amazing facility at that rarest of authorial skills: writing children. Readers who came of age in the Clinton era will be given pause with startling recognition more than once, as Jacob experiences things that we may have thought were unique to our own pasts, from the taste of backpack straps to the shame of realizing you’ve outgrown your best friend. Later, when Jacob is in college, some of this magic is gone, but so it goes, perhaps.

Dolnick writes with a subtle humor and economy of prose that you will forgive the reviewer for describing as “Franzenian,” but the comparison must be made. He rarely rises into lyricism, instead letting description of the circumstances and character’s mental states do most of the work, and the effect is one of creating wrenchingly organic and emotional scenes that will make you want to put down the book to call your mom. Instead of the earth-shaking plot twists of that other author, Dolnick gives us simple episodes that surely all of us have experienced; a death, a pregnancy, an abandoned friend, a broken heart.

Caveat: This is most definitely a young man’s book, and may not resonate as strongly with females, who are presented here (in a not unkind way) almost exclusively from the angle of a Jacob’s mystery and confusion. Similarly, this book may be less relatable for those who are lucky enough to already know what they will be when they grow up.

— Nicholas Mancusi

Hyper-Tech

You can always tell when a Harlan Coben novel is working via one simple mathematic equation, ratified by both MIT and the Pentagon. If you find yourself able to put the book down more than five times over a 48-hour period, there’s isn’t anything wrong with the book, but with you as a reader. Thankfully Live Wire works splendidly, as most readers know, sleep tends to be far less entertaining than turning the next page.

Discounting two novels Coben wrote at an early age (recently re-released with an author’s note/warning from Coben), the bestselling author made his bones writing a mystery series featuring sports agent-slash-private investigator Myron Bolitar. Coben penned colorful plots and created even more colorful characters, including Myron’s former college buddy Windsor Horne Lockwood III (the only Duke grad you legitimately don’t want to meet in a dark alley, who answers his phone with the signature catchphrase, “Articulate”), Esperanza Diaz (aka Little Pocahontas), and Big Chief Momma, a former professional wrestler tag team that now (of course) work for Myron’s agency. The charm of Coben’s earlier works had much to do with the fact that the author pulled off the neat trick of keeping his plots twisting while peppering in plenty of lowbrow humor, seeming to wink slyly to let the reader know he was in on the jokes as well.

Over the years, Coben developed his knack for serpentine plotting, reaching a new level with the terrific stand-alone Tell No One (developed into an award-winning French film). As he left behind Bolitar, Coben perfected the “suburban thriller,” most of his books featuring seemingly normal people living relatively tame lives suddenly forced to confront a past they had either tried to forget, or didn’t know even existed. Recently Coben began effectively utilizing real-life technology as the bones to hang the muscle, such as parental spyware in the tense Hold Tight.

In Live Wire Coben brings social media to the forefront, where former bad girl tennis star Suzze T (aka Suzze Tarvantino), a Bolitar client, seeks Myron’s help in locating her husband, who disappeared after the posting of a cryptic Facebook message. Bolitar has expanded his mega-agency, MB Reps, to represent athletes, entertainers, and, yes, writers (this is fiction, after all). The Facebook message states that Suzze’s husband, Lex, is not the biological father of their son, Mickey (who will be getting his own spinoff series in Coben’s debut young-adult novel, Shelter, due in September). A strange message coming through via email/photographs or other venues is not a new trope for a Coben novel, yet the model delivers because of how this story in particular wreaks havoc on its characters, especially Myron and Win. The strength of these plot devices is that Coben does not approach technology from the perspective of a jaded technophobe, but rather from the perspectives of regular people who are both enamored with, and perhaps a little bewildered by, the power it wields. Just like the parents who create Twitter and Facebook accounts to keep tabs on their teenagers.

But what drives Coben’s works is heart, and in this Live Wire ups the ante. Re-entering the picture is Myron’s estranged sister-in-law Kitty, whom Myron has not seen in 15 years. As constant readers know, Myron has had a close relationship with his family (living in his parents’ basement for many years) so his fractured relationship with his brother’s family is the dark cloud obscuring that silver lining.

The humor can miss as often as it hits, but that is part of Bolitar’s charm. As opposed to many thrillers that come across as deadly serious (and devoid of personality), Myron is a first-rate cutup, adding color to a non-traditional lead character who could have been a standard gumshoe had Coben chosen a less interesting path. Myron is that friend who’ll make you groan as often as he makes you laugh, but it’s that kamikaze hit-or-miss style which makes him endearing.

At this point in his career, Coben has perfected the ability to keep numerous balls in the air, plot threads twisting at once, the readers knowing they will all converge at some point, the suspense lying in just how the author will manage it. What keeps the series fresh, however, is how Live Wire takes familiar characters and continues to reveal more about their pasts, digging up dirt that is hardly fresh in order to create new drama, new dilemmas. And as long as he can keep crafting stories as engrossing as Live Wire, Coben will continue to keep his many fans more than satisfied.

— Jason Pinter, Contributor

Banish the Red Sauce!

Almost three millennia ago, a linguistically distinct tribe began populating a large swath of present-day central Italy. Known as the Etruscans, the ancient Greeks called this race “ Turrēnoi.” The Rasna, as the Etruscans called themselves, were prolific wine growers and experienced wine exporters, sending their products as far as Marseilles and Spain, where huge Etruscan wine amphorae were discovered during archeological digs in the 19th and 20th centuries. Etruscans also loved to entertain with their finest wines and foods, hosting hedonistic revels, according to the Roman historian Tacitus, writing about 250 years after the Romans conquered this proud race and whose kings once ruled over Rome itself.

If it’s an overstatement to suggest the influence of this remarkable people represents the first “Italian” conquest of all things culinary and vinous, today Etruscan culture is nevertheless widely credited by historians of having a critical influence on the Roman republic and empire.

In many ways, then, the disproportionate Etruscan influence on Roman culture and society vividly foretells the story of the rise and dominance of Italian cooking in America and, ultimately, the world over. In the opening chapter of a deliciously written history entitled How Italian Food Conquered the World, restaurant critic and food historian John F. Mariani begins with an obvious, yet essential point, “Simply put, there was no Italian food before there was an Italy.”

From time immemorial, of course, regional cuisines evolved and prospered from Piedmont to Etruria to Puglia, but, as Mariani accurately recounts, much of what passed as “Italian” dishes first served up in America were drenched-in-red-sauce pastas with no discernable regional character.

As Mariani covers this culinary tale, the success of Italian cooking was actually thousands of years in the making. Not even after Italy’s formation as a national kingdom in 1861, which followed nearly a half-century of bloody civil war and deft diplomacy for unification, did a recognizable, “national" cuisine begin to emerge. (The same can be said for the establishment of national language, a single dialect that any citizen could understand. Only in time did Tuscany’s dialect slowly gain wide acceptance across the entire peninsula.) In fact, it would take almost another century before Italy’s family of regional cuisines would enter the world stage, with much of the critical, initial steps in this remarkable revolution initially taking place, paradoxically, in the new world, and especially in the United States.

Fleeing poverty in southern Italy and Sicily and arriving on Ellis Island in New York Harbor from the mid-19th century on, the author describes vividly how boatloads of poor Italians had to quickly adapt to their new home. Obliged by circumstances, Italy’s immigrants were forced to relinquish the prized dishes of their mother or grandmother’s home cooking for two key reasons—either the ingredients weren’t available, or even if they were in rare cases, they were unaffordable.

Two that were—pasta made from durum wheat (also known as “macaroni” wheat!) and tomato paste canned in California—flourished in these rapidly growing Italian communities, and in time, in the global marketplace. Thanks to Cyrus McCormick’s harvesting grain reaper, a farm tool whose design was perfected in about 1850, the Midwest soon became the wheat and corn breadbasket of the U.S. Bounteous harvests lowered the price of wheat in America, making pasta and bread affordable staples.

Then, as Mariani tells this story, when three northern Italian families, then living in White Plains, New York, during World War I, replicated important advances in the canning process originally achieved by a clever Piedmontese entrepreneur, one of these New York families saw a huge economic opportunity out West. Once settled south of San Francisco, the family built a modern canning facility near California’s rich Central Valley, home of vast tomato fields. The company, named Bel Canto and featuring a female farmer, a contadina, on the label, soon had its canned tomato products become the go-to base ingredient in home cooking as well as in thousands of Italian restaurants.

Pasta with tomato sauce, simple pizzas: These were the dishes that fit the bill and pocketbooks perfectly in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These iconic dishes became inextricably linked with Italian cuisine along the entire Eastern seaboard and moved West rapidly; if this or that pasta dish failed the test of regional authenticity, no matter, there was the family to feed and a country to build.

Slowly but surely, as the first few generations of Italian-American families prospered, their cooking broke free of these two culinary clichés. In the post-World War II economic boom, both in Italy and the United States, new generations of savvy chefs and cookbook authors started to focus on authentic regional recipes, the true soul of Italian cooking. Legions of hungry, increasingly fashion- and food-conscious customers, chefs, and customers alike graduated to increasingly sophisticated ingredients, recipes, and regional dishes. With the advent of inexpensive commercial air travel, Italy was soon open to travelers (and future chefs, food, and wine journalists) bearing Fodor guidebooks and, soon enough, college students and hippies trekking across Italy (and Europe) on $5 a day.

Italy rocketed ahead as the fashionable cuisine. On the culinary frontlines, la dolce vita overtook la belle France, as stylish movers and shakers, including chefs and winemakers, discovered the casual chic of all things Italian. Out was “dago red” wine (and the disrespect often displayed to Italian Americans), and in were the fine Barolos, vintage-dated Chianti, and their super-Tuscan reds at prices equal to the best French Bordeaux and Burgundy bottlings. At the same time, many of these fashion and culinary trends also found favor in Great Britain, across Northern Europe and even in the Far East, beginning in Australia and spreading to Japan and China.

To many in the international food and wine world, French cooking was becoming stuffy. More and more restaurateurs, their clients, and food critics gravitated to the more modern style and healthful aspects (and ingredients) of Italian cooking. Every region from “Northern Italian” fare to “rustic Tuscan” to even Sicilian specialties became all the rage.

While simple pizzas and pastas served on red-checkered tablecloths at neighborhood trattoria and pizza joints will always be with us, Mariani admirably dishes out in the final chapters, the story of Italy’s remarkable global ascent to virtual culinary hegemony. Indeed, Italian food has become the most beloved cuisine in America, as exemplified by restaurants from Tony May’s SD 26 in New York to Piero Selvaggio’s Valentino in Los Angeles as well as Wolfgang Puck’s line of gourmet pizzas sold across the country in the local supermarket’s freezer aisle. As further proof of Italy’s astounding international appeal, in Mumbai, India, Mariani quotes a 2009 story in the Times of India: “In the past few years, world-class Italian restaurants (Vetro, Celino, Mezzo Mezzo) in five-star hotels jostled for attention with the standalones (Giovanni, Mia Cucina, Flamboyante)…. Please notice how not a single new French restaurant has opened even in the distant past.”

Like a chef gladly divulging a cherished family recipe, Mariani’s book reveals the secret sauce about how Italy’s cuisine put gusto in gusto!

— David Lincoln Ross, Contributor