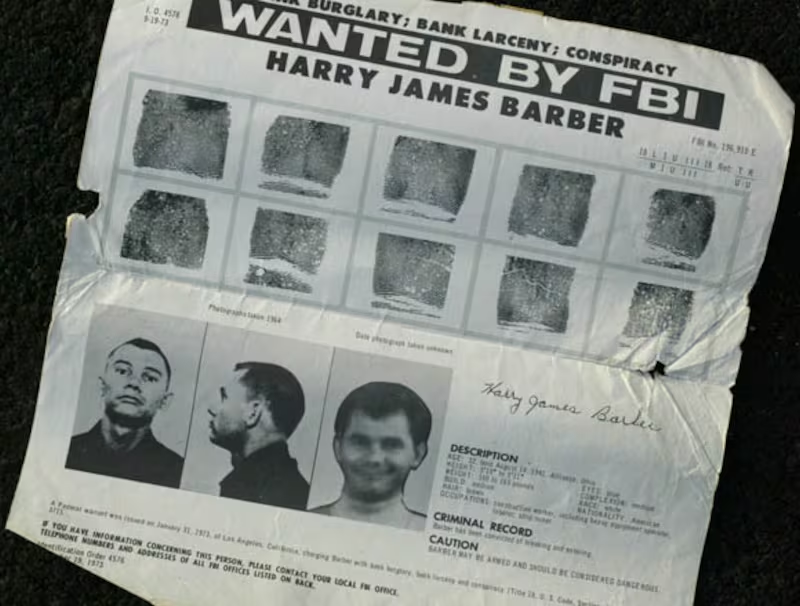

On March 24, 1972, a crew of bank robbers infiltrated—and then spent the weekend rifling through the vault of—United California Bank in Laguna Niguel, California. Their target? A stash of $30 million that was rumored to belong to Richard Nixon, who’d allegedly acquired the loot from Jimmy Hoffa as a re-election campaign “donation” (read: bribe) designed to net the imprisoned Teamsters boss a presidential pardon. The basis for this Friday’s Finding Steve McQueen—which stars Travis Fimmel, William Fichtner and Forest Whitaker, and focuses on gang member Harry Barber’s central role in the plot—it proved to be the largest bank heist in U.S. history at the time, resulting in a haul of $12 million.

And speaking to me a week before the film’s premiere, Barber makes it clear he’s finally ready to set the record straight.

“I’m telling you the whole story. It wasn’t, ‘Can we?’ It was, ‘Do you want to?’ This is how good we were,” the 77-year-old former bank robber says from his home in Southern California, where he’s worked as a general contractor ever since his release from an incarceration that began only after he had evaded FBI capture for eight years.

Recollecting the events that made him and his cohorts—led by his uncle, mastermind Amil Dinsio—notorious, Barber comes across as candid, funny and eager to chat about the heist, about which he’s long stayed silent due to the discomfort it caused his family: “A reporter was after me for a long time, and I told him I really didn’t want to do much of anything until my mother died. She was against all this to begin with.”

The United California Bank saga begins in Youngstown, Ohio, where Dinsio got a tip about Nixon’s secret stash. Barber isn’t sure about the origin of that fateful information—“I really don’t know where it came from, but it came from a good source, that’s all I know”—but it was enough to compel Dinsio to assemble a team that also included his brother James, his brother-in-law Charles Mulligan, and Phil Christopher and Charles Broeckel. “You know, there was only four of us to begin with,” Barber clarifies. “They’re saying seven; there was never seven. There were six involved in this.”

Barber was a natural fit for the job, considering that in the preceding years, he’d developed into an accomplished thief. Which isn’t to say he’d always dreamed of making such work his stock and trade. “It was an accident,” he says about his entry into the business. “We were sitting out in front of Sears, and they had a burglar alarm on the building. We said, well, I wonder what makes this thing work. So we pried it off the building and took it home. And we found out the only thing inside it was a two-dollar battery.”

That discovery was the beginning of a fruitful run of robberies. “This is how it started. Then we started in supermarkets. And then we wound up with the banks,” he explains. “Actually, I should say bank—I was only charged with one bank.”

When Dinsio got wind of what might be housed in Laguna Niguel’s United California Bank, the opportunity was too good to pass up—especially since Nixon wasn’t particularly popular with him or his mates. “He was not one of our favorite people to begin with,” Barber chuckles. “We were told that Nixon was hiding some money. So we figured, he couldn’t cry to nobody. Who’s he going to cry to? He stole it himself!”

Robbing a president isn’t a task to be taken lightly, and Barber and company put considerable effort into planning their mission. On the evening of March 24, they sprung into action. To guarantee that no cops interfered, they sprayed the inside of the financial institution’s main alarm (which Barber refers to affectionately as “the loudmouth”) with a fast-hardening goop normally employed to solidify surfboards. “They all got sprayed,” he remembers. “We had seen it [the goop] used in the past, and we thought we’d try it. It worked very well.”

With the security device disabled, the men took to the bank’s roof, where they blasted a giant hole in the ceiling with dynamite (“I didn’t have enough balls to walk into a bank with a pistol to begin with”). While one would think such a detonation would attract unwanted attention, Barber reveals that they had a reliable method of muting the explosive noise. “We put sand on top of it, to muffle the sound.”

Using a ladder to enter the vault, the crew spent the entire weekend going through the bank’s coffers. “We watched it 24/7,” Barber elucidates about their ability to come and go as they pleased for such an extended stretch, when the bank was closed. “We watched everything to make sure we weren’t coming into a trap.” When they were finished, they had nabbed what Finding Steve McQueen claims was a total of $12 million. Barber, however, suspects the figure was a bit higher.

“I think it was closer to $14 million,” he says. “But you know what—the FBI knows more than we did. Evidently, they were there.”

No matter the exact size of their take, legend has it that Nixon’s money was never found; instead, they’d hit the wrong bank. Barber, though, roundly rejects that notion. “It was his. Part of it was his,” he assures me. As proof, he points to the fact that, despite believing Nixon wouldn’t come after them lest he reveal his own criminal dealings with Hoffa, they were soon under such intense law-enforcement heat that the only explanation was the president’s displeasure with their efforts.

“Usually, when somebody robs a bank, they send four or five FBI agents,” Barber states. “This man sent 125. So you know he was pissed!”

Not that Nixon ever publicly admitted to anything of the sort. With regards to those 125 agents, Barber concedes, “That still doesn’t mean he was saying that’s my money.”

According to Barber, Finding Steven McQueen—its title a reference to his love of the Hollywood icon—gets some details wrong. For one, he and his brother Ronald, a Vietnam veteran who’s depicted as being part of the job, didn’t take a measly $10,000 for their efforts: “That’s not true. I took $12,000, but it had nothing to do with the bank.” Moreover, Ronald wasn’t there in the first place. “To be honest, my little brother wasn’t even really involved. He was not. The FBI knows this!” That, in turn, means that the film’s coda, regarding how his sibling made out with prized valuables, is also apparently false. “[The FBI] placed a gold piece, I guess, in my brother’s apartment [in order to frame him],” Barber asserts. “But my brother died, so it’s over with him.”

As United California Bank heist lore goes, the burglars were eventually apprehended when the Feds discovered their fingerprints on dirty tableware left in their rented house’s dishwasher. Not so, says Barber. “It wasn’t the dishwasher.” Rather, “there was a guy by the named of Dawson, and the [getaway] car was parked in his garage. Now I guess Chuck [i.e. Charles Mulligan] told the man [Dawson] the whole story, and he told the story to the FBI. Then the FBI got ahold of [Charles] Broekel or somebody, and got them to go to court to testify against me. They didn’t even know who I was.”

That’s because, for the eight years immediately following the robbery, Barber was on the lam, living under an alias in rural Pennsylvania—a location he assumed wouldn’t be on anyone’s radar. “Everybody knew that I didn’t like the cold. So I figured the last place they’d look for me was where it’d be cold,” he laughs. “I used to send them postcards all the time from Florida and Hawaii, wishing them Merry Christmas.”

Barber’s luck ran out after the aforementioned testimony put the Feds on his tail, and following a Long Beach jail stint that saw him acquire a driver’s license for notifying the warden that his office was bugged—“I’m the only one in jail who ever had a driver’s license!”—he retired to Southern California, where he’s kept a low profile that’s only now being upended by Finding Steve McQueen. Regardless of whether the movie does his illicit feat justice, he remains adamant that his infamy wasn’t just the byproduct of dumb luck.

“It all started out as a bit. Believe me, we never dreamed this could happen, to rob a bank, you understand? But it was a full-time job,” he says with some pride. “We took this very serious. We were not weekend warriors.”