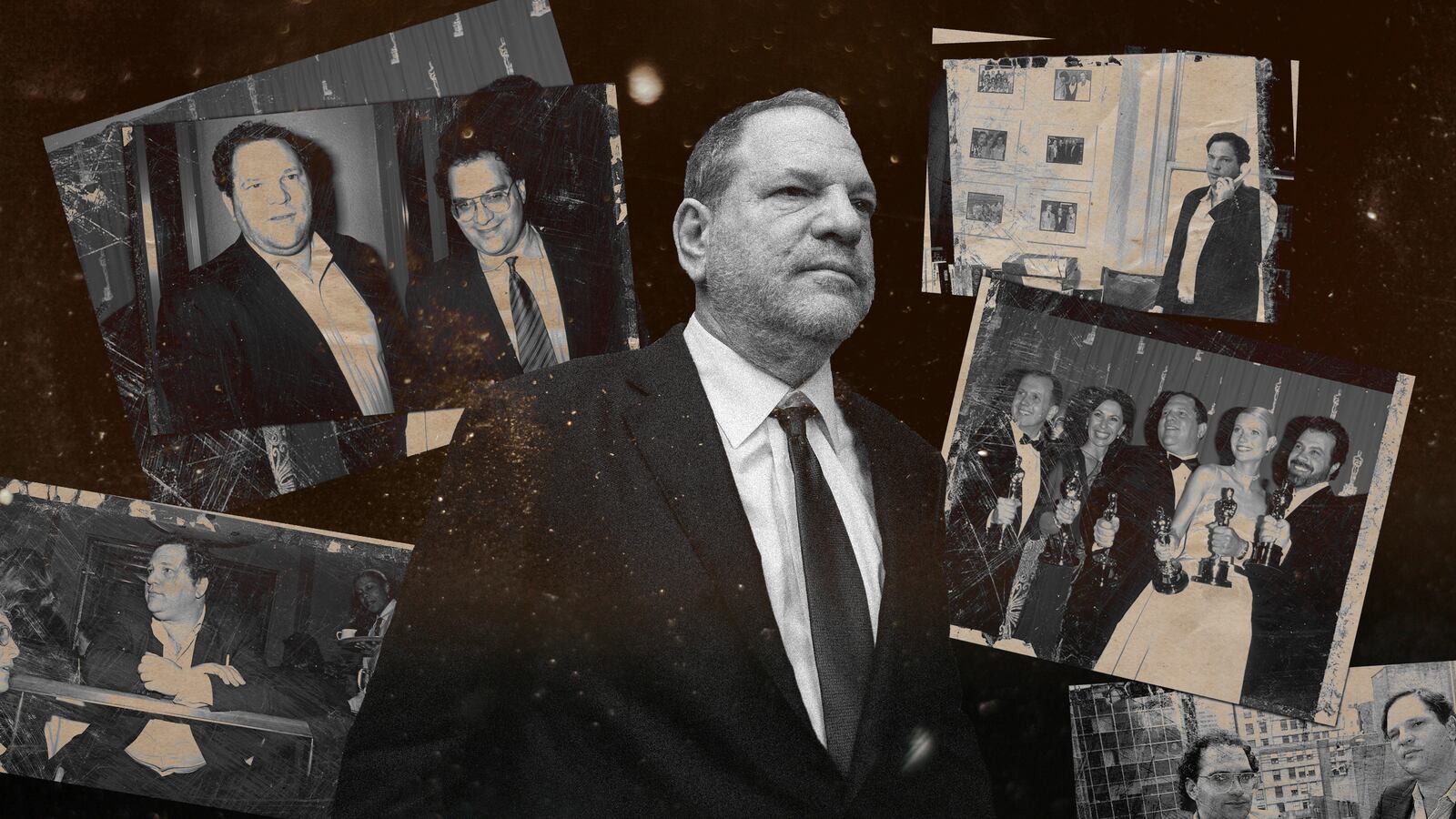

I had planned to begin this review with a list of the most headline-grabbing facts in Hollywood Ending, Ken Auletta’s meticulous account of Harvey Weinstein’s rise and fall in the movie industry. This, I figured, is what most readers want from any review of a book like this: the gossip, the salaciousness, the sleaze. I certainly do.

So I’m sorry to disappoint you, but my plan went south. Don’t get me wrong, there’s plenty of appalling dirt on Weinstein on almost every page. But if you read or watched the coverage of his 2020 trial for rape and sexual assault, you know the worst of it. And frankly I can’t see anyone who skipped the trial or ignored the exposés in the media that precipitated it caring enough about Harvey Weinstein now to read a 456-page book, no matter how tawdry or well-researched it is.

Of course, Auletta puts it all neatly together, so you get the 100 women who accused Weinstein of assault and rape for the last 30 or 40 years. You get plenty of examples of Weinstein screaming and verbally abusing… well, pretty much everyone. How he ate like a pig, how he smelled like shit. And how he lied, especially about his sexual abuses, to everyone who mattered in his world, including his brother and lifelong business partner, Bob Weinstein.

But if there are few bullet-point, headline-grabbing revelations in Hollywood Ending, that is not to say that it is not a thoughtful, probing book. Take its treatment of Bob Weinstein, for example. Bob was around for the whole show, from the brothers’ early days as concert promoters in Buffalo right through the glory days when they taught Hollywood how to take indie films to the mainstream even as they cleverly forged a title roster that balanced artistic films and shrewdly commercial successes. And he was there at the end, casting the deciding vote that banished his brother from The Weinstein Company, watching as Harvey was convicted and sent to prison, and then watching his own career go up in smoke because his last name was Weinstein.

He was also a chief source for Auletta, which is not to say he gets a free ride. Bob, like Harvey, was an abusive screamer. He was an alcoholic, although unlike his unrepentant brother, he copped to his problem and sought treatment. And he, like so many inside and out of the company, enabled Harvey. He may not, as he insists, have known that his brother was a rapist, but he knew full well that Harvey was a physically and verbally abusive bully who constantly and for decades trespassed well past the precincts of decency. And he did little to stop it.

Neither, of course, did anyone else, although rumors of Harvey’s sexual behavior had circulated for decades. Auletta himself, in researching Harvey for a 2002 profile in The New Yorker, found women who would talk about the assaults but would not be persuaded at that time to go on the record. Creditably, he applauds the reporters from The New York Times and The New Yorker who in 2017 succeeded where he had failed.

Hollywood Ending’s real accomplishments are twofold. First, it is nuanced in ways missing from the screaming-headline revelations of the story as it unfolded. Auletta bends over backward to give Harvey his due as a visionary and inventive movie producer and a skillful promoter. No other single individual did more to remake the Hollywood landscape than he did. He found big, multiplex audiences for indie films and foreign films that no other producer had ever found a way to tap. Auletta insists, correctly I think, that you cannot ignore Harvey’s successes in any assessment of his crimes, and not just because those successes gave Harvey the license to act like a pig. More than that, Auletta argues, the good and the bad have to be seen together for us to truly understand what a tragically flawed and compromised figure Harvey was. He was a real-life Jekyll and Hyde, and the insoluble riddle of how so much good and evil could reside in one man is the abiding mystery that gives this book its fascination.

Second, and much more important, Auletta puts Harvey Weinstein’s story in the broader context of Hollywood. There is no doubt that Harvey was enabled by those who worked for him and with him for decades. A horrifying bully and a known philanderer, he was tolerated by his industry for far too long. He was excused because, the logic went, Hollywood has always been a slimy place where moguls preyed on aspiring actresses, whose ambition quelled any desire to call these executives to account. Time and time again, Auletta gives us examples of people who worked for and with the Weinsteins who saw enough smoke to know that there had to be a fire, and yet said nothing. The book’s subtitle, “Harvey Weinstein and the Culture of Silence,” is a clear indictment not only of a man but a culture, for one of the sadder lessons here is that Harvey Weinstein transgressed so successfully and for so long because he had lots of help.

Harvey, of course, exploited this “everybody does it and blame the victim” mentality like no else ever has. In an author’s note, Auletta recounts Harvey’s attempts from prison to dictate terms when the two men were negotiating the parameters of interviews. In one instance Harvey resisted cooperating altogether because he somehow got the idea that Auletta was including the word “monster” in his book’s title. Auletta denies that he ever planned to use the word, even though no one outside of Harvey’s prison cell would probably blame him. But it forced me to look up the word—a word so common that none of us feel the need to consult a dictionary when we use it. It has a long history, going back to the Latin, monstrum, meaning portent or monster, from monere, a warning. And certainly monsters have been with us forever, from the minotaur to Grendel to Frankenstein’s patchwork creation: frightening beings not quite human but all the more frightening for that. They are no one thing, not spirit, not animal, not human, and their terror lies somewhere in the unstable intersection of all those qualities.

One last note—about the ambiguous title that Auletta did go with: Is Hollywood Ending meant to be ironic, i.e., this is absolutely not the kind of story where anyone rides off happily into the sunset? Or is it to be taken at face value? A bad man got caught, justice was served, goodness triumphed? Or is it implying the end of old Hollywood and its casting-couch mores? Not the latter, surely. In what may be the saddest revelation in a book packed with sad revelations, Auletta reports that the one juror who spoke to the press after Harvey Weinstein’s conviction in 2020 “cited the testimony or behavior of two men” who testified at the trial as the persuasive evidence that convinced jurors to convict. Not the several women who spoke about their own assault or that of women they knew. Two men.

This is a hard book to read, more than 400 pages about a disgusting man who did disgusting things. But it is—and as someone who wanted to disinfect himself at the end of every chapter, I say this through gritted teeth—worth the trouble. The Weinstein transgressions that Auletta enumerates may be mostly known, but the indictment of the enabling culture that functioned as a petri dish in which this creature flourished has not gotten its due. If he had done nothing else, Ken Auletta deserves great credit for forcing his readers to confront the fact that evil does not thrive in a vacuum and that Harvey Weinstein, as bad as he was, had far too much help along the way.

They say time wounds all heels. Isn’t it pretty to think so.