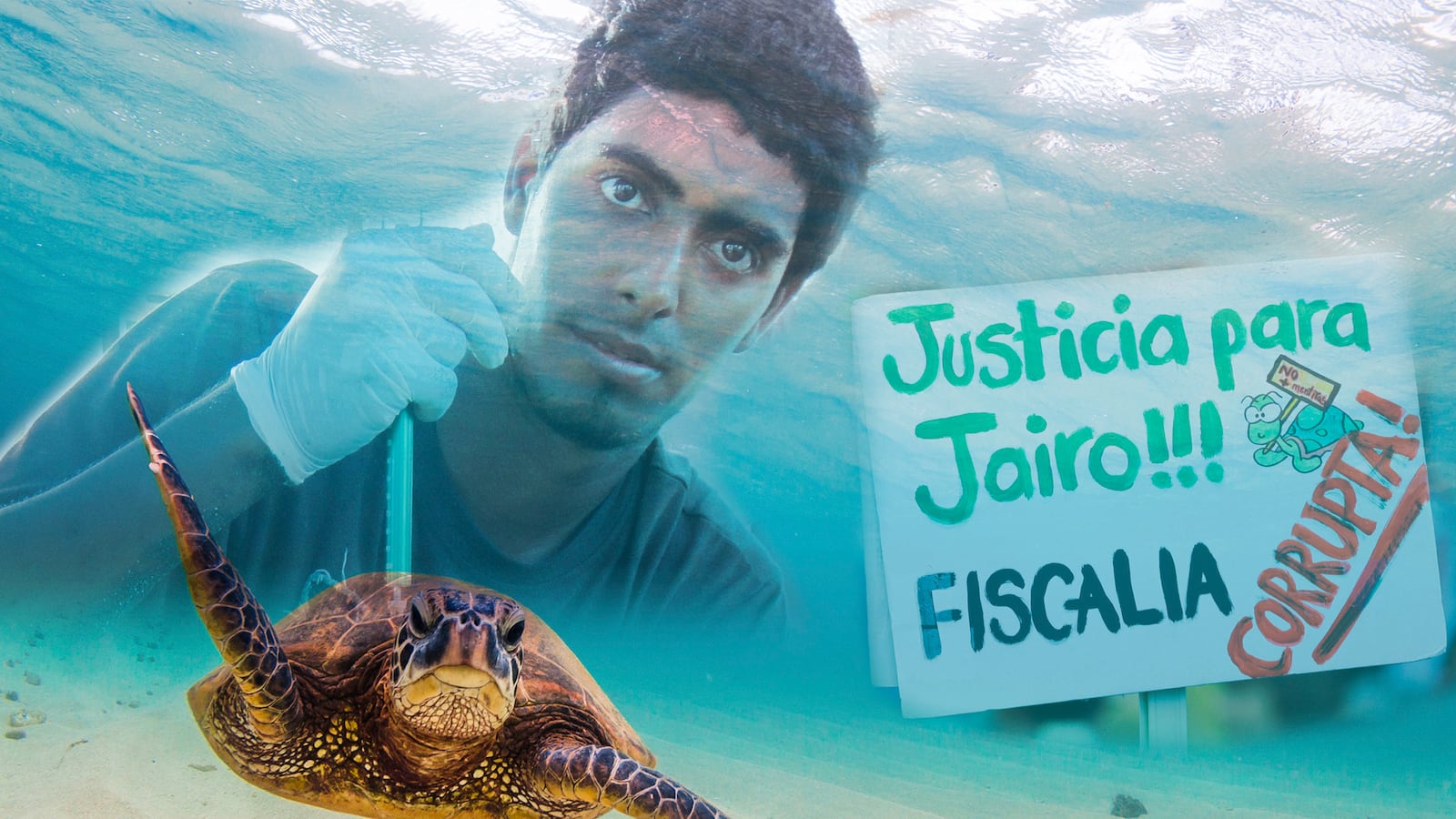

SAN JOSÉ, COSTA RICA — On the night of May 30, 2013, conservationist Jairo Mora saw the last sea turtle he would ever try to save. That night, Mora and four foreign volunteers slipped out of the butterfly-wing gates of the rescue center where they worked on Costa Rica's Caribbean coast and took a drive down the notoriously dangerous Moín Beach. The next morning, police found Mora’s beaten body facedown in the sand. He had been dragged back and forth across the beach until he suffocated.

At the time of his murder, Mora was working to protect the eggs of the endangered leatherback sea turtles that nested on Moín, but his conservation efforts did not sit well with the local poachers who sell the eggs, a rumored aphrodisiac, on the black market for a sizable profit. Before he was killed, Mora had been threatened and assaulted, but he continued to save eggs until his murder.

Mora's slaying was not seen as unusual in Latin America, where more environmentalists are killed than anywhere else in the world. From the Amazon in Brazil to the deserts in Mexico, activists continue to be murdered at a record pace. Just last month, Berta Cáceres, a prominent Honduran activist, was killed in her home after years of protesting against a hydroelectric dam project. In 2014, 88 other activists were killed in the region.

With its reputation for environmental friendliness, Costa Rica had long stood out from its neighbors as a safe haven for environmentalists, and for many, Mora’s murder was seen as evidence of the expanding violence against activists. Now, despite the blemish on Costa Rica’s image, the country’s handling of Mora’s case stands as a rare positive example.

This month, judges doled out the maximum sentences to four poachers found guilty of the crime. The convictions have provided a glimmer of hope in the bleak atmosphere that environmentalists in Latin America face, but overall little has changed.

According to 2014 study by international NGO Global Witness, the average numbers of reported environmentalist murders has more than doubled since 2010. More than 80 percent of these reported killings were in Latin America.

Researchers now compiling data from 2015 believe it was the deadliest year for environmentalists on record. Though better reporting mechanisms are likely responsible in part for the increasing numbers, researchers believe other factors are also at play.

“We think companies are getting more and more desperate to access resources,” Billy Kyte, the lead researcher of the Global Witness study, told The Daily Beast. “The pressure for natural resources is fueling competition between local communities and large extractive industry and dam companies."

This problem is especially acute in resource-rich Latin America, where many large corporations have received swaths of land through government concessions. Those affected by these land grabs tend to live in indigenous or farming communities where land ownership is crucial to survival.

These murders are rarely punished and only a handful of reported environmentalist murders globally have been prosecuted. In Latin America—where impunity is often higher for crimes in general—Mora’s case is one of only a handful of environmental murders to result in a conviction.

With Mora’s case now solved, environmental groups are pointing to the Cáceres murder as an important opportunity to break the cycle of impunity. Due to Cáceres's visibility and notoriety abroad, a conviction for her killing would send a message.

“A credible investigation that results in arrests would help to restore the idea that there is not simply blanket immunity for the murders of environmentalists,” John Knox, an independent expert on human rights and the environment for the United Nations, told The Daily Beast. “If [potential killers] thought there would be accountability there may be people who would still risk it, but there would be nothing like the numbers that you see here.”

Despite mounting pressure internationally and the past threats on Cáceres’s life, the Honduran government has continued to classify the murder as a failed robbery rather than an assassination, and Cáceres’s fellow activists have cast doubts on the government’s commitment to a thorough investigation.

This month, members of Cáceres’s family traveled to Washington, D.C., to call for an independent investigation into the murder, but U.S. officials have thus far said they would not launch a separate inquiry.

While Cáceres’s and Mora’s murders both caught international attention, other killings continued without attracting much notice. In March alone, two other environmentalists were murdered in Central America. Nelson García, a member of Cáceres’s group of protesters, was shot in the face on March 16, and Guatemalan Walter Méndez was shot in his home after receiving threats for his campaigns against illegal logging. If recent years are any indication, the coming months will see many more deaths.

“All of this pressure is because so many people knew [Cáceres] personally, but this happens to countless others all the time,” Knox said. “The murders are just the tip of the iceberg because there are countless environmentalists who are harassed for every one that is murdered.”