The assignment, Tom O’Neill says, “was kind of open-ended.” In March 1999, an editor at Premiere magazine asked him to write a few thousand words about the murders committed by the Manson Family, the 30th anniversaries of which were drawing near. A seasoned entertainment reporter, O’Neill talked to retired cops, prosecutors, and Hollywood hangers-on. He began sifting through old court records. O’Neill was looking for a new angle, and he was determined to go wherever his reporting took him.

Where it took him was far past his deadline, into a kind of journalistic purgatory; this in turn morphed into “full-blown mania,” ensnared him in a lawsuit, and nearly led to financial ruin. The anniversary piece never materialized, and for a long time, neither did anything else. O’Neill kept at it, though, interviewing people linked to the case and uncovering police reports that nobody had looked at in decades. He gradually transformed his Southern California bungalow into “a hoarder’s nest of Manson ephemera,” filled with files, books and binders. When new leads emerged, he jotted them down on a whiteboard, and on scraps of paper connected by arrows. “One door opened another,” he told me recently. “It never was anything I thought would last as long as it lasted.”

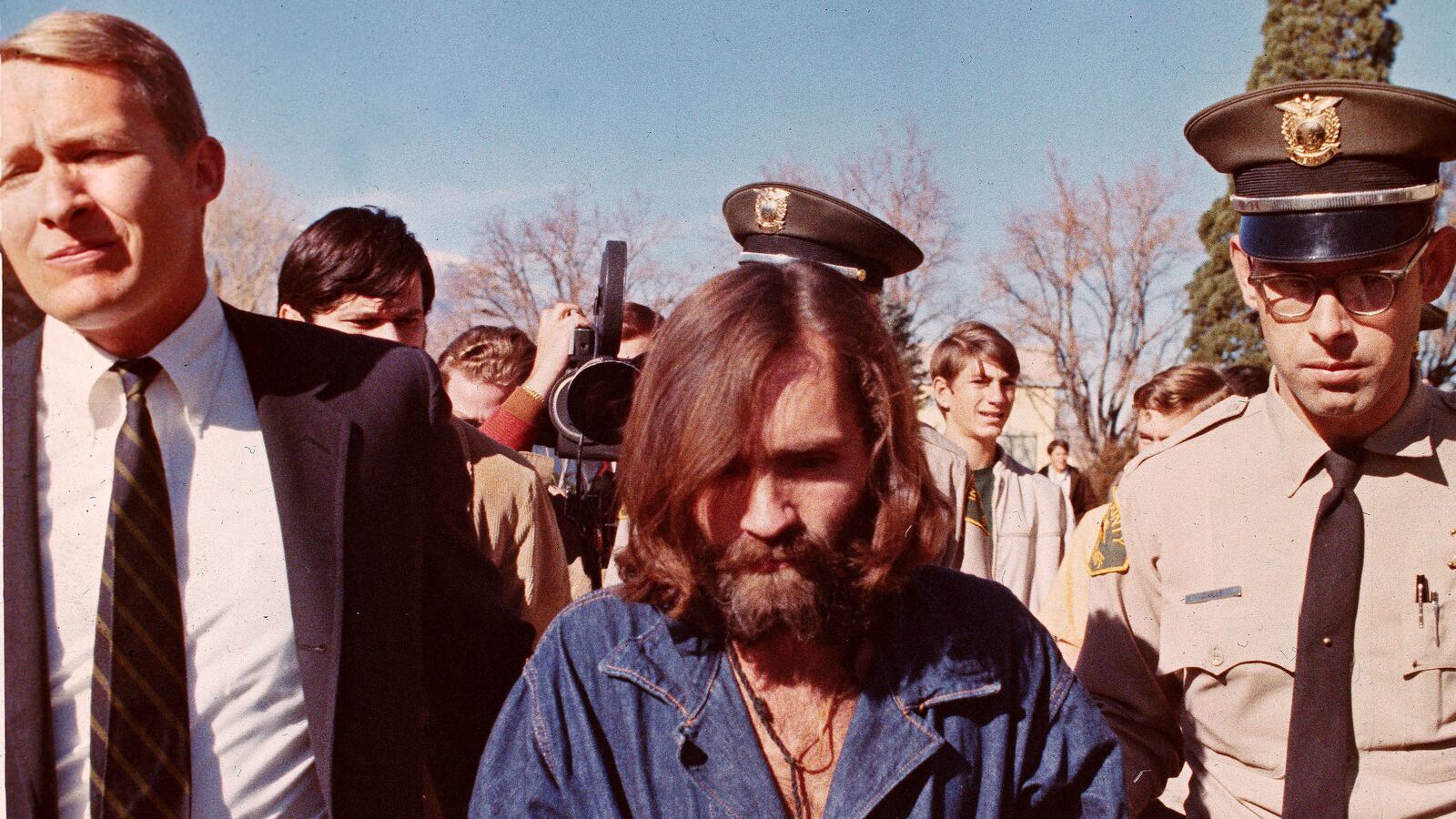

This summer, 20 years after he began his reporting—and nine years since the magazine that commissioned his work went out of business—O’Neill, 60, is finally sharing the results of his obsession. His book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, is a sprawling, fascinating document, a 500-page testament to his enthusiasm for following every lead, even those that sound a little nutty (though the reporting is O’Neill’s, Dan Piepenbring is credited as his co-writer). Throughout, he comes across as diligent and modest, willing to admit that, with the crimes now a half-century in the past, many of his findings are tantalizing but inconclusive. “My goal isn’t to say what did happen—it’s to prove that the official story didn’t,” he writes.

The official story is the one laid out in Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders, the 1974 book often cited as the top-selling true crime title of all time. Bugliosi, who died in 2015, was the prosecutor who secured the convictions of Charles Manson and four of his followers for the August 1969 murders of seven people at the Tate and LaBianca houses in Los Angeles. He maintained that Manson, full of drugs and ludicrous ideas—his apocalyptic worldview was informed by his misinterpretations of “Helter Skelter” and other Beatles songs—orchestrated the killings as a means of setting in motion a war between the races.

O’Neill doesn’t dispute that Manson ordered the murders—“I think he was every bit as evil as the media made him out to be,” he writes—but his reporting made him increasingly skeptical of some of Bugliosi’s claims. “Over the years,” he says, “many people in law enforcement have told me that they never believed the ‘Helter Skelter’ motive. Their theories were always more mundane—they would’ve made thinner material for Bugliosi’s book.”

As he searched for alternative motives, O’Neill began to understand what a writer who covered the Manson trial in 1971 once told him—that the case “will take over your life if you let it.” He cultivated a growing list of sources and made frequent trips to courthouses and sheriffs’ offices. One of his signal discoveries was a set of notes penned by Bugliosi; these, O’Neill writes, suggest that the prosecutor omitted key details that should’ve been shared with the defense team, shielding a well-connected witness—Terry Melcher, a music producer and Doris Day’s son, who died in 2004—from having to answer tough questions about his friendship with members of the Manson Family, and effectively streamlining Bugliosi’s “Helter Skelter” narrative. When shown the notes, Stephen Kay, a prosecutor who worked on the case with Bugliosi, declared himself “shocked,” adding, “This throws a different light on everything… I just don’t know what to believe now.”

Things didn’t go smoothly when O’Neill told Bugliosi what he’d found. “This was the case that made him famous,” O’Neill says, and the notion that his book’s thesis was being called into question enraged Bugliosi. O’Neill interviewed the onetime prosecutor several times, and their relationship was contentious enough that both men recorded their conversations. One day, O’Neill says, Bugliosi threatened a lawsuit, telling him that “the only thing you’re going to be accomplishing is jeopardizing your financial future and that of your publisher.”

Bugliosi never did sue O’Neill, but in a sense, he was prophetic. In 2012, after more than a decade of reporting, O’Neill learned that his publisher, Penguin, was canceling his book contract; soon thereafter, he “became one of a dozen authors Penguin sued for failing to deliver manuscripts.” (He eventually landed a deal with Little, Brown.) At one point in the project, O’Neill had debts totaling $500,000; at another, he “sheepishly” accepted when his father offered a loan.

All the while, O’Neill kept working his sources. He interviewed “way, way more than” 500 different people, he told me, but refused to elaborate for fear that the total would make him “look insane.” His reporting, as his book’s subtitle makes clear, took him to some weird places. Although he’s aware that he might be “criticized for introducing conspiracy elements,” O’Neill examines the closer-than-you’d-think links between government-funded drug researchers and members of Manson’s inner circle of deranged hippies. Likewise, he doesn’t entirely dismiss the theory that some law-enforcement and intelligence operatives realized Manson’s group was dangerous yet did little about it, confident that any crime his followers committed would undermine the broader countercultural movement that opposed the Vietnam War.

O’Neill’s work has armed him with a host of findings, theories, questions and distressing anecdotes. Among them:

* A retired district attorney who didn’t prosecute Manson but “worked in the same office as the DAs who had,” suggested that Manson might’ve been some kind of informant. “It wasn’t the first time I’d heard the theory,” O’Neill writes. In conversation with O’Neill, the onetime prosecutor discussed the search warrant that was served at Manson’s ranch in mid-August, a week after the murders: “They had this massive raid and everybody’s released two days later!” Manson wasn’t charged with the murders until October. The retired prosecutor suggested that someone in law enforcement might’ve wanted Manson and his followers freed that August “because they’d get more out of him by having him released.”

* An alternative theory, embraced by some of O’Neill’s sources, holds that the infamous murders were copycat crimes intended to absolve a Manson Family member of another recent killing. On Aug. 7, 1969, Manson follower Bobby Beausoleil was charged with the ritualistic murder, in July, of a man named Gary Hinman. Beausoleil’s accomplices, also Manson groupies, had yet to be arrested. According to one of O’Neill’s police sources, Beausoleil called the Manson ranch from jail and asked the Family to “leave a sign.” “That night,” O’Neill writes, “Sharon Tate and her friends were killed, and Susan Atkins scrawled the word ‘Pig’ in blood on the front door… just as she’d done on the wall at Hinman’s.” This, some of O’Neill’s sources believe, may have been an attempt to exonerate Beausoleil: if he was locked up for the first murder when the eerily similar second set of murders were committed, maybe he wasn’t guilty after all.

* O’Neill wants to know why, 50 years after the crimes, prosecutors still refuse to share some of the material from their investigations. For instance, the Los Angeles County District Attorney has refused to release tapes of a November 1969 police interview with Manson associate and convicted killer Charles “Tex” Watson. For reasons that aren’t altogether clear, “the DA’s office is guarding them with more fervor than ever,” O’Neill writes.

* Though these were among the most widely covered murders in American history, key details may still be guarded by—or perhaps have gone to the grave with—small-time criminals or entertainment industry types, O’Neill writes. The murders “may have had something to do with a drug burn, or an unknown middleman with connections to Hollywood.”

* O’Neill knows what it’s like to talk to Manson himself. After engaging in talks with, among others, a Manson acolyte dubbed Pin Cushion—“nicknamed for the frequency with which he’d been stabbed”—O’Neill tried to interview Manson. The conversation wasn’t mystifying: “Whenever [Manson] didn’t feel like answering, he’d say something like…‘I got five red wheels on that truck.’”

Chaos, to O’Neill’s credit, isn’t a book that makes claims it can’t support. He raises a series of intriguing questions and admits when he’s stumped. When he botches an interview, he tells us about it. In one chapter, he writes about interviewing Paul Tate, the father of actress Sharon Tate, who was one of the Manson murderers’ victims. When Paul, who died in 2005, didn’t want to answer a question, O’Neill suggested that he should be more forthcoming, “just out of respect to the victims.” O’Neill quickly recognized his own callousness and apologized. As he tries, earnestly and not always successfully, to understand an utterly senseless crime, it’s small moments like these that make this book work.

I told O’Neill that I admired his refusal to speculate when the evidence just isn’t there. He chuckled and said, “That’s why it took 20 years!”

After so much time, O’Neill is understandably thrilled to have his book out there in the world. But when we spoke, he was reluctant to let go of the material. “There’s still a lot to do,” he says, “a lot of loose ends in the research.” He’s thinking he might follow up with a magazine piece—and this time, he’s confident he’ll meet his deadline.