In September of 1992, two months before our child was born, I headed to Pulaski, Tennessee, to attend the Aryan Unity March, a rally held by the Fraternal Order of White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. The location was significant—the original KKK had been founded in Pulaski on Christmas Eve in 1865.

It wasn’t my first Klan rally, but it was a rare opportunity for me to spend time with many of the skinheads and fellow white supremacists I’d known and been corresponding with from around North America. At the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan I’d represent Blue Island, the birthplace of the American neo-Nazi skinhead movement.

The day of the rally was hot, the smell of steamy asphalt hanging in the thick, musty air like the hordes of law enforcement officers littering the rooftops of the town.

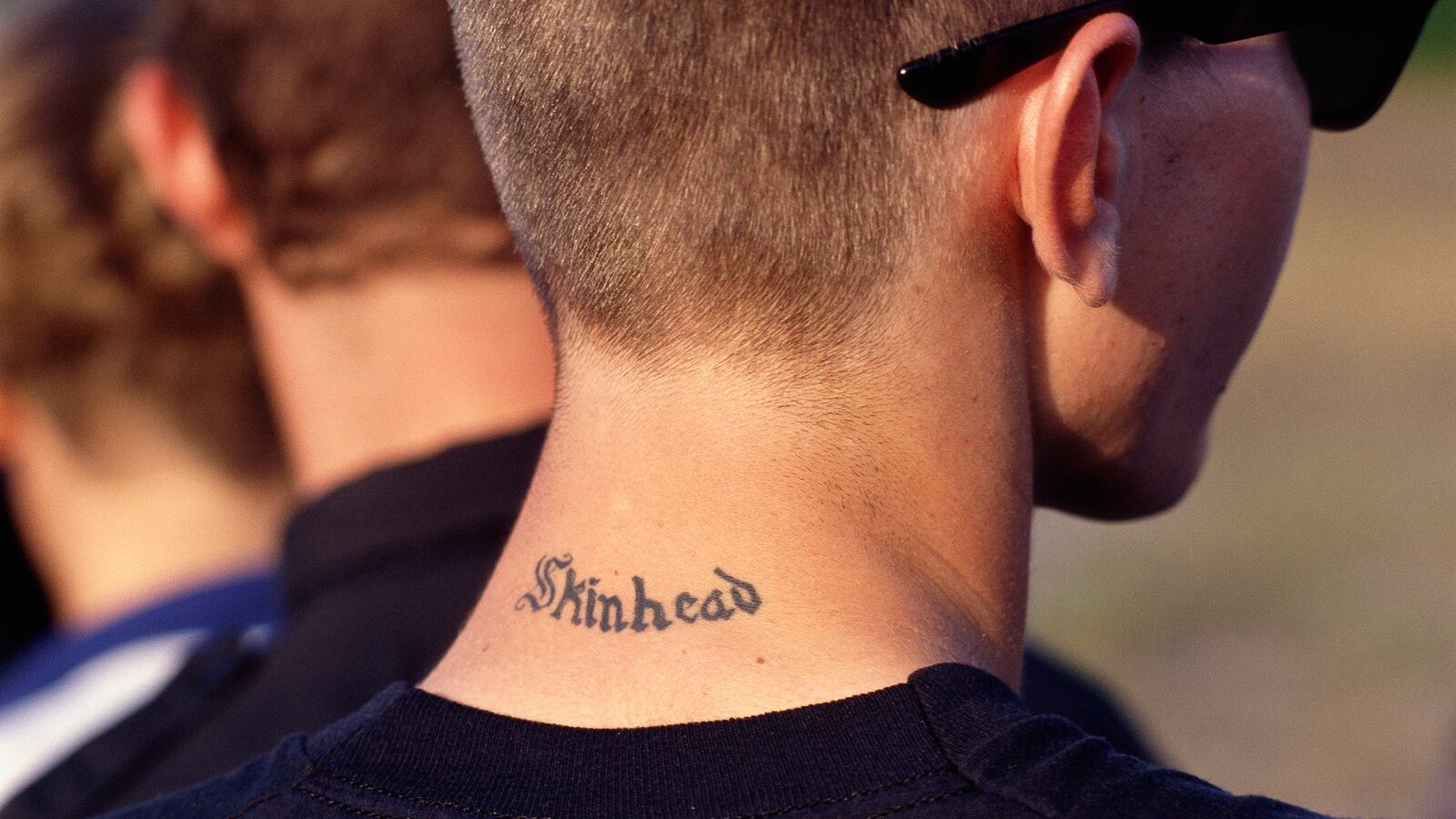

I was dressed for combat: My 14-eyelet black Doc Martens shone slick and my jeans rolled up so the blood that was sure to flow through the streets would not stain them. My head was shaved to a close crop, and I took the thin black suspenders off my shoulders. They hung at my sides, a statement to my enemies that I was ready to fight and defend my race with my sweaty, balled-up fists. The boots were heavy on my feet, and sweat rolled down my back. The humidity was dangerous, and so was the tension in the air. Feds were not so subtly stationed all over the streets, taking our photos with cameras bearing lenses as long as their arms.

Hundreds of skinheads, people dressed in Klan robes and Nazi regalia, and racists of a more general ilk congregated at the designated staging area. Men with bullhorns barked orders for us to come together and shouted motivational white-power cheers, which were followed by stiff-armed salutes.

The air was thick with banners—Confederate flags, Nazi battle flags, hand-painted placards with sayings like “God Hates N**gers,” “Join The KKK,” and “Save the White Race. Unite!”

The attacks of September 11, 2001, hadn’t happened yet, but with the American white-power movement in full swing, most Americans were living in fear of every move we made. As far as mainstream America was concerned, we were the most dangerous extremists within our borders. And the truth was, they were right.

The lust for blood was palpable. There were among us militiamen in camouflage with riot helmets and Nazi armbands.

As rebel flags and swastikas cut furiously through the air, so did the chants and protests from hundreds of people who had gathered to oppose us. Black and white, old and young, male and female, they were united by their commitment to stop us from marching. They were clamoring for us, only held back by a thin blue line of Pulaski policeman and Tennessee state troopers.

The mob of counter-demonstrators grew by the second, and they were loud, far louder than we were, even with our bullhorns.

They held up peace fingers, and we flipped them off, taunting them with racist epithets and a barrage of “die, race traitor” and “f**got cocksucker” obscenities.

They carried signs demanding world peace.

We thought we carried the weight of the world.

That’s when it dawned on me: I ached for Lisa more than anything, more than I wanted a white homeland even. For a brief moment I became lost in scanning the faces of some of the counter-protestors. I felt for the first time as if I were coming face to face with some of the people from my past. There was the gay brother one of my friends had, who was always interesting and funny and kept mostly to himself. And my black teammates from my Eisenhower football team who had never given me trouble despite the horrible things I said about them and the violence I facilitated. The thoughts and words from the last five years of my life were taking on new resonance in my head—as if I were hearing things I’d said played back to me, and they sounded like they were in someone else’s voice.

Why was I here and not at home with my pregnant wife whom I adored, with my hand on her belly, taking in every moment with her? I suddenly felt guilty and out of sorts. I didn’t respect these people, the Klansmen, the racist clergyman wearing a priest’s collar around his neck and a KKK patch over his heart, the mother carrying her infant with a tiny Klan hood on, the inbred hick with missing teeth and a beer-stained “N**gers Suck” T-shirt.

There were fellow skinheads here too, “brothers” and “sisters” whom I related to from neighborhoods like I came from, urban jungles, rather than Southern swamps. But even with them, I was starting to question what this struggle was about.

It was about pride, I rationalized, being proud of our white heritage and standing up against those who wanted to take that away from us. My thoughts drifted back to my earliest memory of holding Lisa in my arms, her pleading eyes searching deep inside me for my truth. “Why do you have so much hate inside of you?” she’d questioned. “You’re so caring and gentle to me sometimes. Which one is the real you?” Suddenly I wasn’t so sure.

Ahead of me, the Grand Dragon of the prevailing KKK faction within our group proclaimed this was once again the birthplace of a white revolution. N**gers, queers, and Jews were the enemy.

I knew all that—n**gers were raping our women and forcing drugs on our youth. It didn’t happen in my town, but presumably it was more prevalent in theirs. Jews controlled our lives, and queers destroyed white propagation. And somehow—choose the reasoning you like—the fact that we never saw evidence of these claims was itself evidence of their existence. That was how good the Jews and their secret plan for a “New World Order” were at obscuring their crimes.

I saw that the peace-loving protesters, gathered by the hundreds, waving peace flags and holding hands singing folk songs, had resorted to ripping up chunks of concrete from the sidewalk to violently pelt us with.

We inspired so much animosity in those who believed in only peace that they were trying to hurt us with violence.

The Nazi salutes had tired my arm, and the cries for white power had strained my voice. When the march came to an end and my comrades were celebrating by getting hammered with booze, I was hit by the disturbing thought: how would I know if this whole thing was simply an endless cycle of excuses to fight and drink and commiserate? To belong to an exclusive club of other people more fucked up than you?

I felt stuck in a hole too deep to climb out of. The life of a violent white supremacist was all I’d known through nearly every single one of my teen years. Who would I be otherwise? Where would I go?

Confusion overwhelmed me, and I felt as if someone had landed a solid blow to my solar plexus. Along with my breath, my commitment was knocked out of me for the first time, and for a brief moment I clearly saw there was a serious problem with my reality.

Excerpted from the book White American Youth by Christian Picciolini, published on Dec. 26, 2017 by Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2017 Christian Picciolini.