One can imagine the concern of young Francis Scott Key that day in early September of 1814 as he pulled on his boots, kissed his family goodbye, and left his Georgetown home to confront the British in Baltimore.

The 35-year-old lawyer had learned that the invading army had arrested an American doctor, and he was on his way to help negotiate the man’s release in the midst of the War of 1812.

It couldn’t have been easy to leave his home and family behind—after all, the Brits had burned large portions of Washington, D.C. only a handful of weeks earlier.

But the mission was a success in more ways than Key could ever have imagined.

Not only did the physician go free and the Americans triumph in the Battle of Baltimore, but while Key watched the British mercilessly bombard Fort McHenry while under enemy custody during the long night of September 13, he was inspired to write the poem ‘Defence of Fort McHenry’ that would be set to music and eventually become as ubiquitous at U.S. sporting events as mustard-stained shirts and peanut shells.

With the creation of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ Francis Scott Key became a national treasure (albeit one with a complicated history).

For nearly two centuries, Key’s contribution to his country has been honored in ways large and small.

A bridge spanning the Potomac River from Georgetown to Rosslyn, VA opened in 1923 and was named after him, as was a larger version built in 1977 that stretches across the Baltimore Harbor.

Money was raised for a monument at his gravesite; a memorial park in D.C. was donated to the National Park Service in 1993; and countless monuments popped up around the country from Baltimore to San Francisco to commemorate the one-hit national wonder.

But, despite the best intentions of the National Park Service, one important memorial failed to survive through the centuries. The Georgetown house that Key left that early September day in 1814 disappeared many years later…at the twilight’s last gleaming, one might say.

It’s not unusual to hear of missing art or jewelry or even historical monuments. But an entire family home?

The Key residence at 3518 M St. NW was born shortly after the new American country came into being. The house was built in 1795 by Thomas Clarke, a merchant and real estate investor. Ten years later, the Key family pulled up in their horse-drawn moving truck.

Throughout the turmoil of the early 19th century, the family called the residence their home. Some reports say they moved their living residence elsewhere by 1830, but the patriarch of the family kept his offices in the space until his death in 1843. That year, the life of Francis Scott Key may have ended, but the life of his house was far from over.

On July 18, 1896, The Washington Post announced that the Key house was to be turned into a hotel. Assuring readers that the new owner was “anxious to preserve the historical house,” the article detailed the four-story addition on the west side of the house, the two-story addition to the main section, and the destruction of the chimney, “the only part of the original structure to be torn down” that were planned.

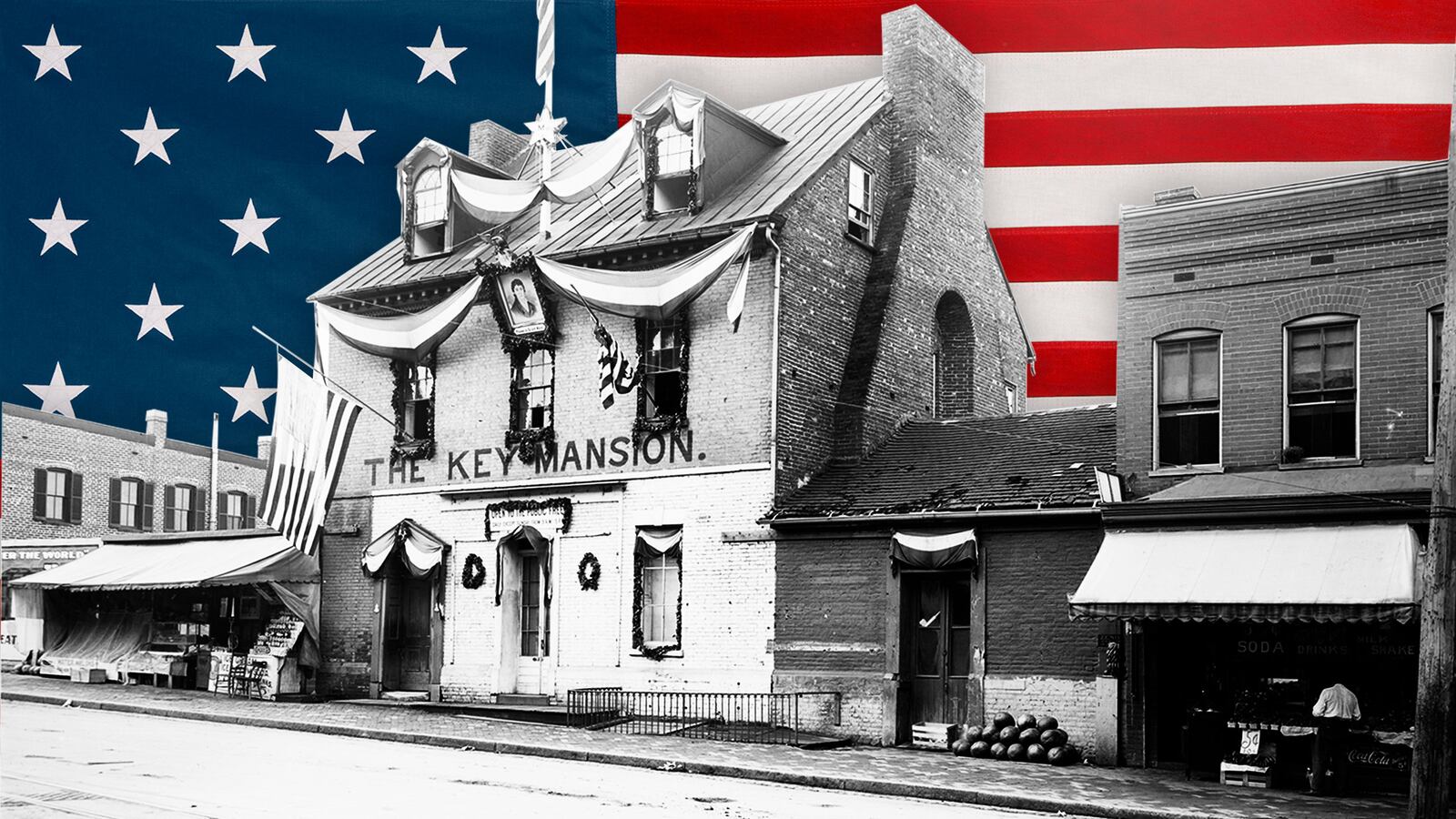

After the hotel fell out of use, the house was reborn as “a dry-goods emporium, a blacksmith shop, and a cobbler’s store,” according to People. It didn’t survive this time unscathed. Alterations were made to the home and big black block letters were added to the front proclaiming “The Key Mansion” to try to increase its tourist appeal (or at least serve as a guide to bumbling visitors). In 1931, the entire block including the Key house was purchased by the government; ownership shifted to the National Park Service two years later.

Despite now being under the government’s purview, the fate of the Key house was far from settled. Over the next decade, an arduous debate ensued over the future of this ungainly structure. The entire street was slated for demolition—first as a river beautification project, then to make way for a new road—so something had to be done with it. But what should that be?

The interested parties were split down two sides: one thought the structure was too far gone and conservation was pointless; the other favored restoring it to its former—original—glory…albeit in a new location.

The opposition camp had a few heavy hitters. Key’s great-grandson, a former champion for all things related to his famous forebear, had switched sides by this time and argued that there was not enough left of the original structure to save.

Stuart M. Barnette, a Park Service historical architect, added his rather harsh opinion that, “neither the ruins are of great architectural importance, nor was the man whose name is associated with the structure.”

But their objections weren’t enough; the preservationists eventually won the day.

By the fall of 1947, Congress had generously approved $65,000 for the creation of a Francis Scott Key National Monument (the project was projected to cost over $100,000) that would sit on the east side of the Key Bridge and include the reconstructed house. With a new site picked out, quick work was made of dismantling the home.

“By the dawn’s early light, and on through several weeks, workmen carefully made diagrams and photographs, numbered the parts, tore the building down and moved the pieces to the park area on the southeast corner where Key Bridge intersects with M Street,” Tom Zito wrote in a piece for The Washington Post in 1981.

The pieces of the home were painstakingly recorded in order to make reassembly that much easier. The woodwork was packed up in boxes and stored in safe locations, while the bricks were moved to the new site and left in a pile overseen by the National Park Service.

But while the Key house was being taken apart brick by brick, the bill providing the money for the restoration fell out of favor, and President Truman threw a wrench in the plan by way of a pocket-veto on June 27, 1948.

“After the reconstruction prospects died, so did much incentive for the Park Service to zealously guard the brickpile,” one-time Park Service historian Barry Mackintosh wrote in a report written in July 1981. “With Georgetown in the midst of its restoration boom, it would have been remarkable if the old bricks had not soon found their way into walls, walkways, and patios around town.”

As for the woodwork, it was stored in prime storage space--space that was too good to be used for languishing beams. The various boxes were moved to other, presumably less desirable, locations, but no one bothered to note where those locations might be. “In time, few old Service hands remained who could recollect the unrecorded fate of the materials,” Mackintosh wrote.

It would have been destined to fade out of memory…except that Washington Post journalist Tom Zito discovered the National Park Service’s secret in 1981.

“Whoops, I was afraid this was going to come up one of these years,” George Berklacy, the Park Service’s then-director of public affairs, told Zito when confronted about the whereabouts of the Key house.

“At negligible cost to the taxpayers, a small but intrepid team of Park Service preservationists (including the author) responded to the publicity by crawling under bridge abutments and scanning maintenance storage areas rumored to be Key house repositories in a hasty search for remnants,” Mackintosh recounted in his report a month later. “The failure of these efforts to unearth so much as a Keystone, board, or brick was duly reported in broadcast interviews by radio and television reporters taking ill-concealed delight in such bureaucratic bungling—or so it seemed to their discomforted subjects.”

No amount of searching could fix this dilemma. The Key House was good and gone.

Still, Key got the best memorial there is. Over two hundred years later, the top singers in the country continue to show off their high notes every year as they belt out his story of “the land of the free.”