IKOM, Nigeria—When fighting began last year in Cameroon’s anglophone regions, Grace Agbor—along with Ezekiel, her half-brother—fled the town of Akwaya. They went to the Nigerian border town of Ikom, where they lived with a fellow Cameroonian they’ve known since childhood.

Less than three weeks into their stay in Ikom, the half-siblings attended a meeting of young Cameroonians in the town to discuss the humanitarian situation back home, and a compatriot told them about another group of people from Cameroon discussing plans to reach the United States with the help of smugglers in both South and North America.

Five days after the Agbors joined the group called “Dream America,” Ezekiel sold some parcels of family land and his car to raise about $10,000 and handed it to one of the founders, who then passed the money to the agent for a smuggling ring based in Lagos.

The money, Ezekiel was told, covered the cost of traveling by land to Senegal, an air ticket from Senegal to Ecuador, and then the fee for a spidery network of smugglers who eventually would help him reach the U.S. southern border with Mexico.

This may sound extraordinary, but migration is globalized. People are fleeing poverty, the ravages of climate change, wars, and repression all over the world. And, sure enough, as attention turns to the drama of the migrant caravan heading up through Mexico toward the U.S. border, a handful of people swept up in the impromptu parade do indeed come from far-flung corners of the globe, including Africa.

The Trump administration has tried to use that easily anticipated fact to push racist buttons and raise the specter of terrorism. It’s the kind of fear-mongering that has served President Donald Trump so well in electoral politics. But each of these people has his or her own story.

For Ezekiel, life as a refugee began as a matter of language. He was at risk in largely francophone Cameroon because he is an English-speaker, and he is part of a growing number of anglophone Cameroonians who are migrating in search of new routes to lives of hope and safety.

The country descended into conflict in 2016 when the government repressed peaceful protests by English-speakers against perceived marginalization. It turned into a war when separatists declared western Cameroon an independent nation last October. The deaths of more than 100 civilians have been documented since then, along with dozens of soldiers killed by the rebels, but the figures probably are much higher.

More than 180,000 mostly anglophone Cameroonians have been displaced (PDF) during the crisis, including at least 21,000 refugees registered in camps in the southern Nigerian state of Cross River. Many others who—like Ezekiel—are able to afford the cost, have traveled thousands of miles from the country in search of new opportunities.

“He [Ezekiel] left Senegal for Ecuador in the middle of the year along with two other men from Cameroon who had also raised the money required for the trip,” said Grace, 34, who is six years younger than her half-brother. “Hopefully,” she said, “three others from the group, including me, will travel before the end of the year.”

Traveling from West Africa to Ecuador is relatively easy. A decade ago, the South American nation passed a new constitution that established an “open door” policy for all foreigners visiting the country. A visa was not required to enter, making Ecuador one of the most liberal countries in the world in terms of accessibility, and turning it into a popular destination for people who wanted to travel to or through the Americas (Ecuador later reinstated visa requirements for Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Somalia).

Since Dream America was created in October 2017, close to a dozen people have departed for South America. It is not clear how many have made it across Central America and Mexico into the U.S., because many migrants fail to keep in touch.

“One crossed the U.S.-Mexico border late last year,” Grace said. “A couple of them have called to say they were denied entry by U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials.”

Ezekiel and the two other Cameroonians arrived in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, in June. From there, they traveled by road through Colombia and over trails in the Darien Gap, a lawless forest. The route was well documented by CBSN last year, following an Iranian Christian refugee, among others.

“[Ezekiel] explained to me on the phone how armed bandits asked him to take off his clothes as they searched all over him for money,” said Grace, who often gets phone calls from her half-brother. “He said he saw dead bodies in the forest, including those of children.”

In Panama, the migrants turned themselves over to authorities in the hope that they would be granted visas to pass through the country freely. They were then detained in a military camp, as officials took time to check their identities. Eventually, they were released after being granted exit visas to move to the next country, a pattern that is common in countries in Central America.

Another smuggler then took the Cameroonians and several other migrants from West Africa and Asia across the Panamanian border into Costa Rica, where he handed them over to a truck driver who smuggled them up through Nicaragua to Honduras.

After Ezekiel spent weeks in Honduras, another smuggler helped them get on a bus that took them through El Salvador to get to Guatemala. The migrants eventually crossed into Mexico and arrived at the city of Tapachula last week. Here, they were given a 20-day permit to cross on to the next country, which everyone understood would be the United States—if they could find a way.

Then, days after the Cameroonians got to Tapachula, much to their surprise they were joined in the city by a caravan of thousands of Central American migrants, mainly from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, who have fled violence and poverty in their countries. As of Monday, more than 7,000 people in that “caravan” had crossed into Mexico.

Later this week, Ezekiel and his compatriots plan to follow the caravan walking up the Pacific coast to Arriaga, which will take a number of days to complete. From there, they intend to board a train to Tijuana.

“They are so many [Central American migrants] saying they cannot continue the journey, but we’re determined to make it to America,” Ezekiel told his sister over the phone as she let The Daily Beast listen in.

“We’ve been told that the Mexican government are likely to bow to pressure from the U.S. to stop migrants from reaching the border. Many people are getting discouraged, but we are not going to look back,” Ezekiel said. In fact, there’s every indication the Mexican government will facilitate the trip at this point.

As The Daily Beast reported on Monday, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to cut aid to Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico if they didn’t stop the caravan, prompting those governments to send security forces to their respective borders—to little effect. Then, without evidence to support the claim, Trump said the caravan was organized by Democrats and one of their major donors, billionaire George Soros. He also tweeted without proof that “criminals and unknown Middle Easterners are mixed in.”

“Apart from the Africans and Central Americans, the people I’ve seen here are mostly Nepalese, Indians, Bangladeshis, Cubans, and Haitians,” Ezekiel said. “We first met some of them in Colombia, as we attempted to cross into Panama.”

In recent history, Africans and Middle Easterners make up a small fraction of migrants seeking to enter the United States. NBC News reported on Monday that from a total of over 400,000 crossings, about 3,000 people from the Middle East and Africa were apprehended at the border during the last fiscal year.

Figures from the Mexican government obtained by Voice of America show that between 150 and 700 African migrants arrived per day at Tapachula in 2016, with a total of 19,000 migrants arriving from Africa and Haiti in the same year.

A significant number of these migrants are Cameroonians. According to statistics from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) published by Al Jazeera, the number of Cameroonian asylum seekers to Mexico increased from 23 in 2016 to 105 in 2017, the year the conflict in the English-speaking regions turned into a war, while those applying for asylum in the U.S. also increased by nearly 140 percent—from fewer than 600 to more than 1,300—from 2012 to 2016.

The number of Cameroonians seeking to reach the U.S. could grow even greater as the conflict in the western regions extends further.

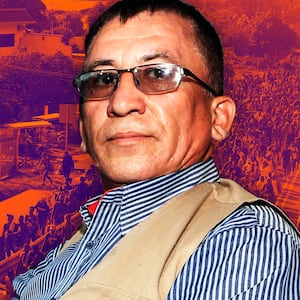

Cameroon’s 85-year-old president, Paul Biya, easily won a seventh term on Monday after receiving more than 71 percent of the vote. But the fact that just 5 percent of eligible voters in the English-speaking regions turned out to cast their ballots shows that anglophones, who are now clamoring for independence, are less motivated about the local version of electoral politics.

“I will only return to Cameroon when Biya leaves office,” says Grace. “For now, my dream is to be in the United States of America.”