A team of 200 scientists unveiled the first-ever picture of a black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope on Wednesday—a remarkable leap in astrophysics that provides an unprecedented glimpse into the depths of the universe’s abyss.

“We have seen what we thought was unseeable,” Shep Doeleman, the director of the Event Horizon Telescope project, said at a press conference. “We have taken a picture of a black hole.”

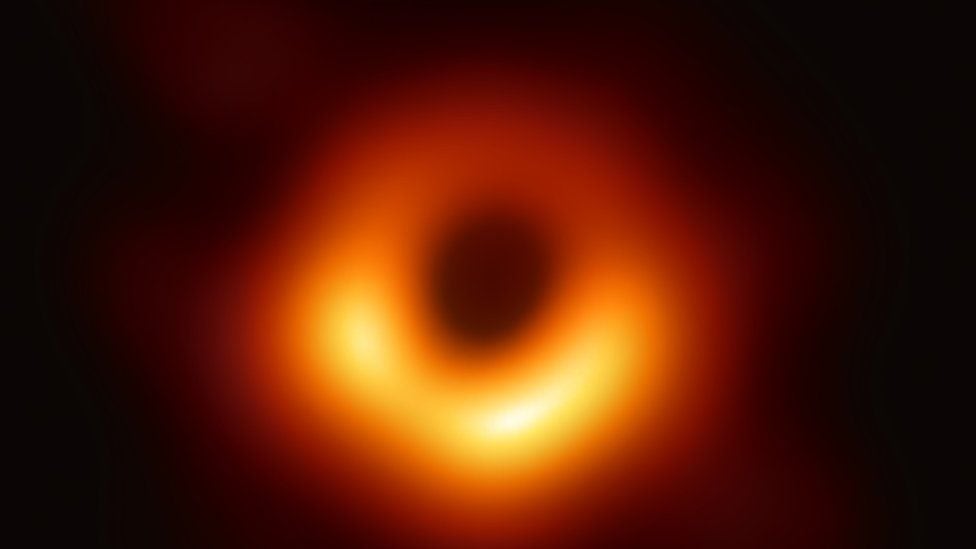

The photo of a glowing, irregular orange ring surrounding a small black circle, shows a massive black hole at the center of the nearby Messier 87 galaxy.

It’s impossible to actually see the black hole, because it’s so dense that it sucks in all the nearby light. Instead, the picture shows the hole’s silhouette, cast against the intense brightness of the hot gases and plasma that scientists think surround it. At some point, those gases cross the hole’s “event horizon”—the point at which nothing can escape its powerful gravitational pull—and are drawn into the blackness.

“Even though those processes are things that could happen, we have not seen any of them happening in front of our eyes to be able to understand it,” Dimitrios Psaltis, an Event Horizon Telescope project scientist at the University of Arizona, told The Verge before the image was released. “By taking a picture very, very close to the event horizon, we can now start exploring our theories of what happens when I throw matter onto a black hole.”

The irregular shape of the orange glow seems to support Einstein’s theory of special relativity, which postulates that matter moving towards us will appear brighter than matter moving away from us.

“Einstein told us 100 years ago exactly what the size and the shape of that [black hole's] shadow should be, Doeleman said at SXSW last month. If we could lay a ruler across that shadow, we’d be able to test Einstein's theory of the black hole boundary.”

Getting this picture wasn’t easy. While the hole is millions of times more massive than the sun, it’s also tens of thousands of light years away.

To get the picture, scientists needed a telescope about the size of the Earth. They approximated that with a global network of massive radio telescopes scattered across the globe, in places like in Chile, Antarctica, and Hawaii, that picked up radio waves cast off by the hole.

The telescopes captured about five petabytes of data, on half a ton of hard drives—which the University of Arizona's Dan Marrone likened to “all of the selfies that 40k people will take in their lifetime.”

The data was so massive that it couldn’t even be transferred digitally—it had to be flown in, which caused problems when winter storms in Antarctica made the data inaccessible for months. And it reportedly took so much computing power that scientists had to wait for hard drive technology to catch up before they could process their results.

But in the end, the millions of gigabytes of data were mashed together in a supercomputer—creating the final picture shown today.

The first time the researchers saw the final image, Doeleman said, there was a sense of “astonishment and wonder.”

“There was such a buildup, there was a great sense of release, but also surprise,” he added. “When you work in this field for a long time, you get a lot of intermediate results. You could have seen something that was unexpected—but we didn't see something that was unexpected, we saw something so true [...] I think any scientist in any field would know what that feeling is, to see something for the first time.”