“The horror film is a very political genre,” writer/director Guillermo del Toro said in an interview with Time magazine in 2011.

He was speaking from a place of experience. Del Toro’s creature-filled Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) showed the horrors of Franco-era Spain. In his cable-TV series The Strain, a ruthless, politically well-connected businessman is as much a villain as any of the tyrannical vampires. Even del Toro’s big-budget, robots-versus-monsters action flick Pacific Rim (2013) doubles as an anti-pollution story.

Del Toro admittedly approaches his craft from the perspective of a leftist—and when it comes to filmmakers operating within the horror genre, he’s far from the only one. The godfathers of modern horror cinema were almost entirely liberal peaceniks.

“If you meet all the people who make horror films, you discover they are very nonviolent, they’re politically active and knowledgeable, and anti-war,” writer/director Mick Garris says in the 2009 documentary Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film, with examples including heavy-hitters and luminaries George A. Romero, Tobe Hooper, David Cronenberg, Stephen King, Joe Dante, Clive Barker, and Roger Corman. “They have opened themselves up to all of these possibilities, and it’s the people who repress them who are the ones you have to look out for.”

One of the more obvious specimens of political horror is Romero’s groundbreaking 1968 zombie movie Night of the Living Dead. Critical appraisals frequently highlight the film’s subversive reflection on the decade’s civil-rights struggle and unrest over the war in Vietnam. (For instance, it starred Duane Jones as the hero—at a time when it was unusual to cast a black actor as the lead in a film with an otherwise white cast.)

“I thought it was about revolution,” Romero says when discussing his film in Nightmares in Red, White and Blue. “We were ’60s guys and…sort of pissed off that the ’60s revolution didn’t work. Peace and Love didn’t solve anything in the end, in fact, shit was lookin’ worse. And I said, what would be a really earth-shattering thing that would be revolutionary and that people would refuse to ignore? The dead stop staying dead. Oh, and here’s one thing more: They like to eat living people!”

This is to say nothing of Romero’s other Dead installments, such as Dawn of the Dead (1978), which tackles consumerism; Day of the Dead (1985), which takes a swipe at the US military; and Land of the Dead (2005), which is a class warfare-focused picture, with hints of Iraq War commentary:

And Romero definitely wasn’t alone in being a “’60s guy” horror auteur disillusioned by a chaotic decade that was to them defined by failed idealism, the Cold War, and a grueling American war. Bob Clark’s Deathdream (1972) is explicitly a Vietnam War protest film, in which a soldier comes home as something truly tragic and monstrous. David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone (1983), based on the Stephen King novel, follows a psychic who tries to stop a future president from nuking the Soviet Union:

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre—perhaps the perfect little horror picture to emerge out of the ’70s and ’80s—was in part shaped by the political and cultural anxieties of the era. The marketing for the film was designed to intentionally mislead viewers into believing that it was based on a true story. Hooper has said that this was a direct commentary on how the nation was “lied to by the government about things that were going on all over the world”—Watergate, the “massacres and atrocities in the Vietnam War,” the 1973 oil crisis, and so on.

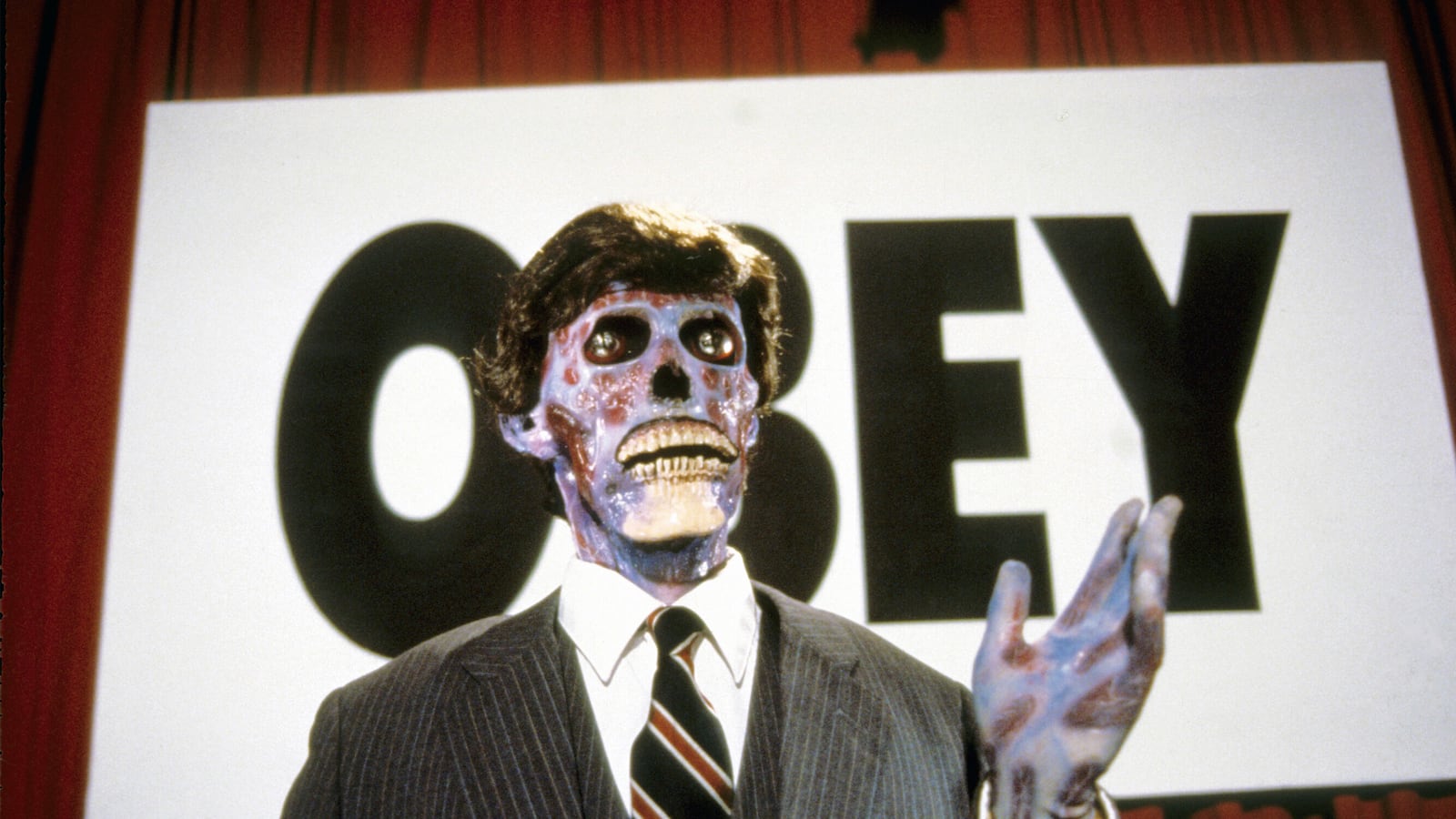

And the legendary John Carpenter (famous for Halloween, The Fog, and The Thing) certainly didn’t let go of his angry, countercultural self as he entered the late Reagan era. His 1988 sci-fi movie They Live took assault-rifle-heavy aim at the decade’s materialism, excess, and conservative dominance.

“[Reaganism] just pissed me off so much,” Carpenter said, explaining what motivated him to make They Live, and what he saw as the destructive “unrestrained free enterprise” and “kill a commie for Christ” attitudes of Reagan’s America were his primary targets.

At this point, you might be wondering what to do if you’re craving some popular conservative horror. One answer, at least for social conservatives: The boobs-and-blood-filled slasher films of the 1980s. These largely apolitical movies—packed with exploitative carnage and sex—nonetheless have a common theme that Moral Majority types can get behind: If you’re a kid who has premarital sex, does drugs, binge-drinks, and parties like a fool, you will be severely punished.

So if you’re a diehard liberal who’s into horror film that remind you how America has fucked up in the 20th century, put on some zombie movies. But if you’re a hardcore traditionalist who wouldn’t mind watching sexy teens pay for their sins in open arteries and torn flesh, then fire up the Friday the 13th franchise: