In 2007, under the watch of insolently lounging house cats in a Northern California living room, I opened the lids of four battered cardboard boxes. Out rushed the smell of a vanished world: a physician’s patient records and hand-written notes untouched for decades, disintegrating photographs, stale cigarette smoke, x-ray images of Adolf Hitler’s skull, wax-sealed packets of narcotics, and allegedly poisoned food. The boxes exhaled the air of Nuremberg, Germany, from 1945 to 1946, when 22 of the top Nazi leaders awaited and began their trial by an International Tribunal. The author of the materials in these boxes, US Army psychiatrist Douglas M. Kelley, was the first mental health expert to examine the Nazi prisoners.

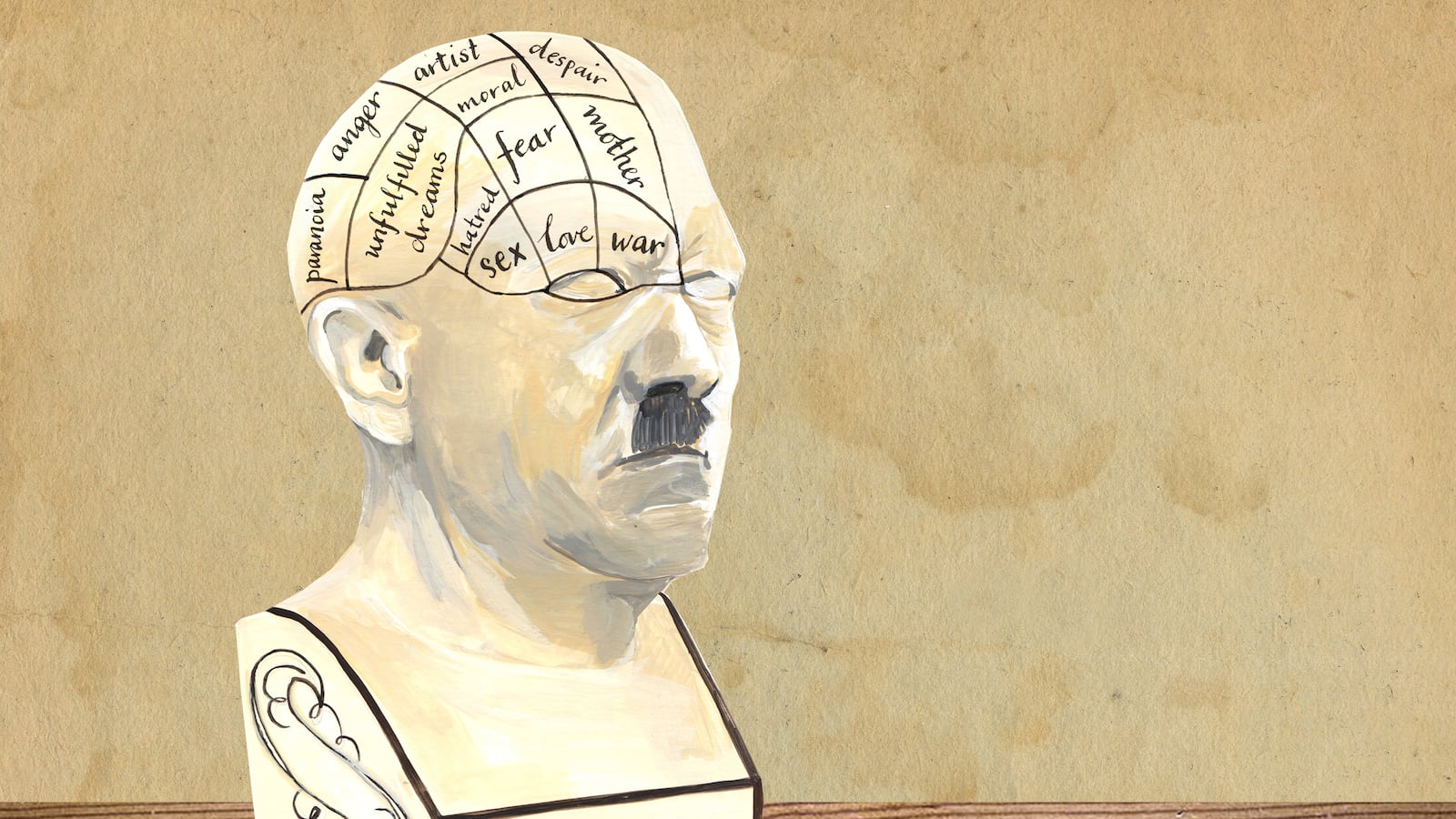

I arrived to look at the boxes at the invitation of Kelley’s son. In August 1945, his father had received orders to go to a hotel in Luxembourg converted into a temporary prison, where Kelley met such infamous Nazi leaders as Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Julius Streicher, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, and Karl Dönitz. Dr. Kelley’s assignment was to certify their mental competence for the trial to come. Just 33 and supremely confident in his abilities, the psychiatrist had more ambitious plans for his time spent with the men widely regarded as the worst criminals of the twentieth century. He wanted to discover the essence of the “Nazi personality.” If he could identify mental disorders and psychological traits common to the Nazi leaders, he could point to others among us capable of committing similar crimes.

After the U.S. military moved the Nazis to a jail in the Palace of Justice complex in Nuremberg, Kelley gave them a battery of Rorschach inkblot tests, among other assessments. He spent hundreds of hours talking with the Nazis in their cells, probing their past, motivations, and psyches. He assessed all of the 22 defendants, including Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, who feigned amnesia and held a paranoiac belief that his jailers were giving him poisoned food. Kelley felt most intrigued, though, by the remorseless Göring — long Hitler’s second in command — whose charm, intelligence, and culture made Kelley wonder how such a man could so absolutely lack a conscience. Looking into the Nazi’s eyes, the physician often saw something of himself. Kelley and Göring forged a bond based on mutual respect for their shared brainpower and skills as master manipulators. Each used the other: Kelley helped Göring end his longtime addiction to the narcotic paracodeine and pass letters to his family, and Göring aided Kelley’s understanding of the complexities of the Nazi character.

When the trial began in November 1945, Kelley had already started to reach conclusions about the Nazi personality. None existed, he believed. The Nazis were psychologically normal. Nazi evil was not only banal, as Hannah Arendt later asserted, but its potential was widespread, especially in American politics and business. “I am quite certain that there are people even in America who would willingly climb over the corpses of half of the American public if they could gain control of the other half,” he said.

These conclusions unnerved Kelley and eventually led him to change the focus of his career from psychiatry to criminology. His personal connection with Göring rattled him even more deeply, and as Kelley fell into alcoholism, workaholism, and depression, he faced his own capacity for evil.

Kelley’s study of evil had turned into something personal. In Kelley’s mind, Göring had possessed a combustive mix of admirable and atrocious qualities, many of which the psychiatrist shared. On New Year’s Day 1958, standing in front of his family, Kelley took his life by gulping cyanide, just as Göring had done a dozen years earlier. What the psychiatrist had learned from the Nazis about human behavior was appalling. What he discovered about himself hurt more.