HONG KONG—There is rage here. Locals streamed onto the streets on Sunday. Many stores shuttered for the afternoon with signs hung by the proprietors saying they’re out, and everyone else should be, too. First, a few hundred thousand gathered in Victoria Park, a starting point for many demonstrations. Then more showed up, even as the sun was about to set.

They were dressed in white, demanding that the city’s political leader, Carrie Lam, step down. A three-word chant echoed through the streets: faan sung jung, or,“We’re against extradition to China.” There is an extra layer of meaning in this phrase, because sung jung is a homonym with a term that means to pay one’s last respects, recalling an idea shared by many Hongkongers—that their city is waning.

Here’s why they were marching: The city’s government has proposed an extradition law—called the Fugitives Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill. If approved, it would allow the city to extradite individuals in Hong Kong to anywhere in the world, even when no formal extradition agreements exist, as is the case with mainland China.

Police gather at a rally against a controversial extradition law proposal in Hong Kong early on June 10, 2019.

PHILIP FONG / AFPIn theory, the Fugitives bill wouldn’t lead to extradition based on political charges. Hong Kong’s government has consistently said that it won’t have an impact on the freedom of speech or freedom of the press, and wouldn’t push away foreign businesses that operate in the city. But the bill covers a broad spectrum of economic crimes, which critics say provides more than enough cover for the Chinese government to nab dissidents and those who are politically non-compliant, then move them to mainland China to stand trial. Moreover, the chief executive, whom the population sees as a stooge of Beijing, would have the final decision in all cases, not local courts.

The bill’s supporters say that it was designed to plug loopholes in Hong Kong’s laws to cover territories and countries that don’t have formal extradition agreements with Hong Kong. These include Macau, Taiwan, and mainland China. In particular, the Fugitives bill’s formulation was brought on by a case where a Hong Kong man murdered his 19-year-old girlfriend in Taiwan. But the man is currently serving a jail sentence in Hong Kong on separate charges, and Taiwan’s authorities have said that they will not request his extradition.

People aren’t buying it. Since the guarantee of a fair trial isn’t included in the bill, their worry is that the Chinese Communist Party will be able to use economic charges as cover to move high profile or influential critics of Beijing to mainland China, where they will be detained and interrogated.

As white-shirts marched through the city at a glacial pace, “Hong Kong” became a controlled or censored term online in mainland China. Searches on Weibo yielded only posts from pro-Beijing media bodies or government accounts. China’s state broadcaster aired a live feed of road repairs in Bishkek. Posts from or about the rally on WeChat—the dominant social media platform in China—could only be seen outside of the Great Firewall.

Organizers say that more than 1 million people participated in the march—that’s one in every seven people who are in the city. Many more watched. For hours, traffic was at a standstill, and demonstrators were stuck in up to a dozen subway stations as they tried to join the march. Many who were present have never been part of a protest rally before. Police place their estimate at 240,000, though they have a history of offering head counts that are off by an order of magnitude.

A paper of 'No Extradition' is held by protesters during the clashes with the police at Legislative Council in Hong Kong after a rally against a controversial extradition law proposal in Hong Kong on early June 10, 2019.

PHILIP FONG / AFPSome participants tried to initiate a sit-in, but that wasn’t part of the day’s agenda, nor are there plans for one moving forward. In 2014, a lengthy occupation of public space by the Umbrella Movement failed to change how the city elects its political leader. If anything, since then Beijing has redoubled efforts to exert its influence in Hong Kong. The fact is, when it comes to Hong Kong, the Chinese Communisty Party is, for now, able to tolerate dissent because the populace holds no bargaining chip, and a moral appeal has never attracted the interest of China’s leaders. The best that Hongkongers can do is to captivate public attention, and a million people following the same dress code managed to accomplish just that.

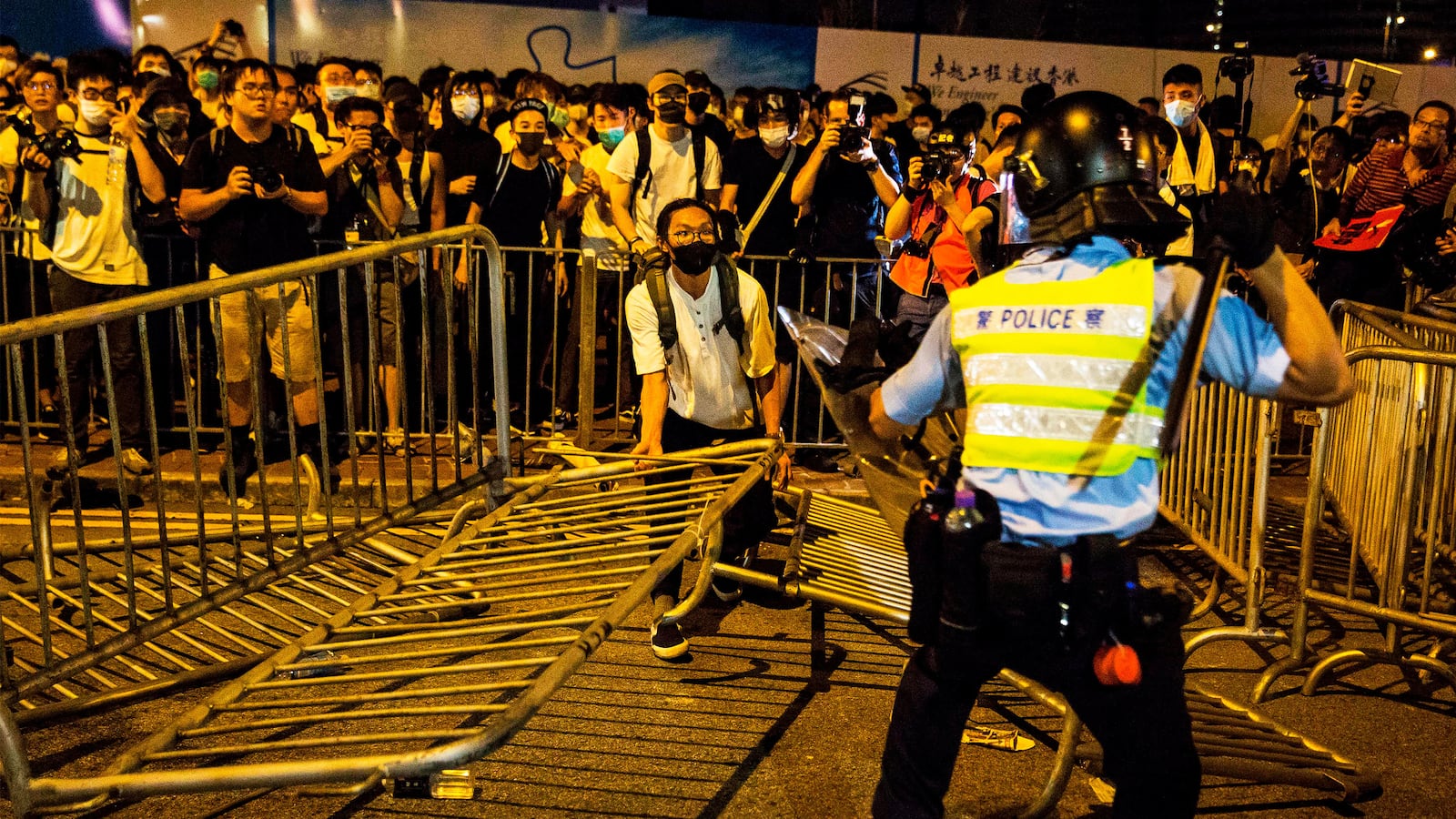

By midnight, much of the crowd had dispersed, though several hundred people remained outside the city’s Legislative Council building through the night. Emotions were still running high, and small groups tore through the barricades. Police arrested at least seven individuals, including two who they say were attempting to interfere with the official effort to count protestors. Some officers used pepper spray and batons. The standoff continued into the night, with most of the last protestors leaving by 3:00 a.m. For a gathering and protest of this scale, it was remarkably disciplined and relatively peaceful.

The discontent on display is rooted in Hongkongers’ determination to uphold the “One Country, Two Systems” policy that was outlined before 1997, when the city’s sovereignty was returned by Great Britain to China. Breaking that policy means undermining Hong Kong’s semiautonomous legal system and leaving individuals on Hong Kong soil exposed to the Chinese Communist Party’s judiciary.

At a briefing in Hong Kong attended by Reuters, CNN, CNBC, Kyodo News, and the Financial Times, Beijing officials even told foreign journalists to “inject positive energy” into their coverage of the matter, using a phrase that has several layers of meaning in China, and has been appropriated by the Party to link nationalist sentiment with spirituality.

Even before Sunday, legal professionals were publicly expressing their dissatisfaction with the Fugitives bill. On Thursday, between 2,500 and 3,000 lawyers—including legal heavyweights like a former High Court deputy judge—staged a silent march in the city’s central business district. At least one local judge’s name has appeared on a petition against the bill. The Law Society of Hong Kong submitted an 11-page document to the Legislative Council, writing that the legal amendments could “conveniently be used for political persecution and suppress freedom of speech.”

A local media tycoon and opposition figure, Jimmy Lai, called the bill “a massacre of our freedom, of our legal system, of the free press” and straight up labeled Hong Kong’s chief executive as “evil.”

Given the Fugitives bill’s coverage of a slew of economic crimes, but the potential of abusing it to inflict political damage, various chambers of commerce have also registered their concerns, including the American office, which said there are “too many uncertainties” within the bill, questioning the rush for it to be passed as law.

Even now, Hong Kong’s chief executive said she sees no reason to yank the Fugitives bill. If passed, it would make her the key decision-maker in extradition cases. Speaking to the press on Monday morning, she suggested that Hong Kong could become a “fugitive offenders’ haven” if the bill didn’t move forward, and that “this work has to continue to be done.”

Protesters block the protest area of Legislative Council with barricades during clashes with police after a rally against a controversial extradition law proposal in Hong Kong on June 10, 2019.

PHILIP FONG / AFPSunday’s actions felt a lot like the Umbrella Movement of 2014. In fact, those who showed up passed through or by two of the three sites occupied for more than ten weeks nearly five years ago. There were callbacks to those days throughout the day, with some people hoisting yellow umbrellas—the Movement’s symbol. But what was different this time was the unity found in the crowd. There were no factional and philosophical differences. It was a matter that drew opposition in all camps except those that are resolutely pro-CCP.

Things in Hong Kong are getting more tense. Last Tuesday evening, 180,000 gathered in Victoria Park, where Sunday’s march started, for a candlelight vigil commemorating the Tiananmen Massacre 30 years after the crackdown. On that night, ahead of the solemn event, participants were already chanting slogans against Hong Kong’s chief executive, the Chinese Communist Party, Chinese president Xi Jinping, and the Fugitives bill. And in three weeks, a protest rally will be held on July 1. It’s an annual affair on the anniversary of the city’s handover to China. At its peak, in 2003, half a million people hit the streets, sparked by a national security proposal that was eventually scrapped due to public pressure. Turnout for this year’s iteration is expected to be huge, too.

At its core, what happened on Sunday in Hong Kong reflects the population’s belief that their city’s semi-autonomy must not be encroached upon. The people weren’t asking for more privileges, like when they demanded fully democratic elections in the past; rather, they were expressing a simple, visceral distrust in the Chinese government.

On Wednesday, June 12, Hong Kong’s lawmakers will review the highly controversial Fugitives law. Have they been persuaded to table the bill? At the moment, nobody can say for sure. Those who were at the march had no illusions about their (in)ability to sway governmental policy. But as long as they still have the right to protest and assemble in public, they’re going to shout No! whenever they can, a million voices at a time.