Pay Dirt is a weekly foray into the pigpen of political funding. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.

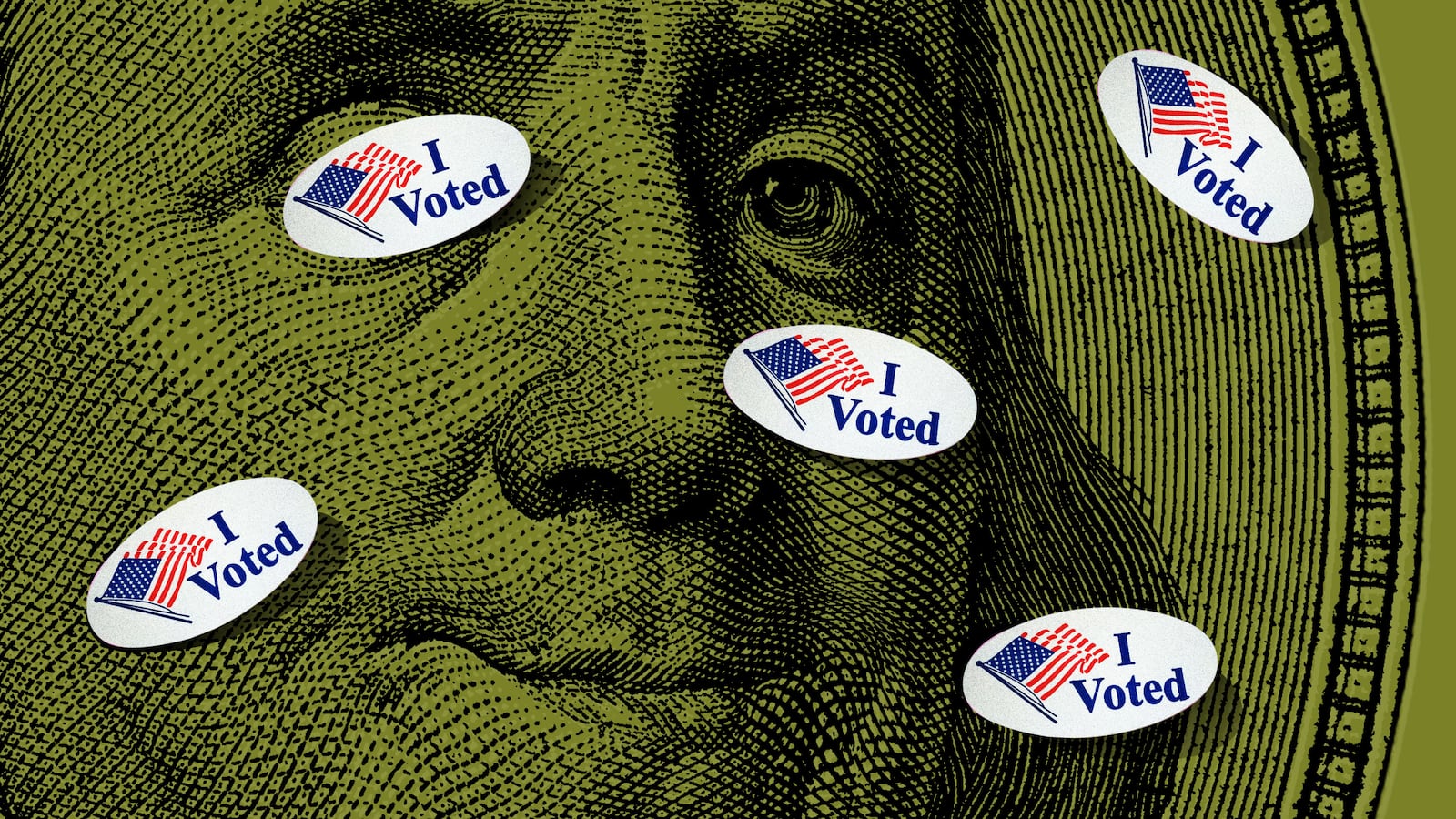

Government watchdogs have long accused the Federal Election Commission of failing in its mission to enforce laws regulating money in politics. Next week, however, those questions will come from members of Congress, when the FEC faces its first oversight hearing in years.

Rep. Joe Morelle (D-NY), ranking member on the House Administration Committee, which will host the hearing, told The Daily Beast that the FEC must be modernized, or political money will continue to flood the system and outmatch the voices of everyday voters.

“The FEC simply is not keeping up with modern campaigns. There is more money coming into elections than ever before, most of it dark and undisclosed, and it’s increasing at an exponential rate. It increases the risk for corruption and is a threat to national security. Voters’ voices are drowned out and they have less insights into who is trying to influence their votes and their representatives,” Morelle said in a statement.

“Congress should not and cannot wait to pass reforms to put the FEC in position to enforce the law and hold candidates, committees, and mega donors accountable to voters,” he said.

The Democrats plan to use the moment to draw attention to what they see as the FEC’s inadequate enforcement of campaign finance laws, making the case for reform. Their concerns apply particularly to issues like the influence of dark money and foreign contributions, which Democrats and transparency advocates have been raising alarms about ever since the Supreme Court issued its landmark Citizens United decision in 2010.

Democrats have a wish list, drawing from the Freedom to Vote Act. Reforms include empowering the agency’s general counsel to take action where the commissioners have failed, and opening new channels for complainants to bring unresolved matters directly to the courts. But Republican commissioner Allen Dickerson has proposed new controversial steps that would further restrict the OGC and give commissioners the power to micromanage investigations—a proposal that was tabled for discussion after Morelle pushed back last month.

Watchdog groups are also applauding the hearing. These transparency advocates have been frustrated for years, as the FEC’s six-person bipartisan panel has frequently failed to attain the necessary four votes to act on enforcement matters—even in major cases where the agency’s general counsel recommends action.

Brendan Fischer, deputy executive director at Documented, told The Daily Beast that the agency has walled itself off from oversight, and congressional hearings are “one of the few remaining ways to hold the FEC accountable to its mission of upholding and enforcing the laws governing money in our political system.”

“The FEC is largely shielded from judicial oversight, with commissioners hiding behind ‘prosecutorial discretion’ to insulate their decisions from review by courts,” Fischer told The Daily Beast. He added that this sense of immunity appears to extend to the commissioners themselves, with GOP commissioner Trey Trainor “recently blowing off an investigation by the FEC’s ethics watchdog without consequence,” referring to Trainor’s refusal to cooperate with an internal ethics investigation into his appearance at a political event.

Ahead of the hearing, Democrats on the House Administration Committee asked the FEC to provide data about its enforcement decisions—specifically where the commissioners failed to act on enforcement recommendations from the agency’s nonpartisan office of general counsel. The data is revealing, showing that over the last four years, the commission has failed to reach the necessary majority consensus in nearly two out of every three cases that it closed.

More unnerving for transparency advocates is the FEC’s failure to follow the recommendations of its own general counsel. Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision opened the door for super PACs, dark money, and unlimited contributions in elections, the FEC has not acted in dozens of cases where the OGC recommended otherwise.

For instance, the OGC has recommended action in 59 cases alleging unlawful super PAC coordination. The commissioners did so in just seven of those cases. And in cases involving potential committee status violations, the FEC acted on five of OGC’s two dozen recommendations.

The Democrats are also disappointed in the FEC’s limited ability to identify and regulate foreign money filtering into elections. And on that issue, the FEC has taken up the OGC’s recommendation less than half the time, the data shows. Almost every one of those decisions not to act—11 out of 13 times—were related to former President Donald Trump.

Last year, The Daily Beast reported that Trump has posted a conspicuously remarkable undefeated record against campaign finance allegations—43 and 0. Democrats on the Administration panel also asked for FEC data on Trump investigations, and found that the numbers had increased in the meantime, with Trump surviving all 56 matters since he declared his candidacy in June 2015.

Of those 56 cases, OGC recommended that the commissioners find reason to believe a violation had occurred in 26 of them. The GOP commissioners voted down all 26.

Government transparency groups know this data all too well, having filed years of complaints that have been validated by the OGC only to be shot down by a deadlocked commission.

Saurav Ghosh, director of federal reform for nonpartisan watchdog Campaign Legal Center, told The Daily Beast that the FEC’s inaction has had lasting negative effects on the democratic process, and public accountability is “long overdue.”

“For well over a decade now, the FEC has failed to enforce the laws that govern our federal elections, and the result has been a drastic increase in political spending, commonsense laws being broken without recourse, less transparency for American voters and more influence for wealthy special interests,” Ghosh said.

“This ideological split, with at least half of the FEC’s six commissioners routinely refusing to enforce the law, has gone on far too long,” he added. “A discussion of this topic on the floor of the House is long overdue.”

Asked for comment, FEC Chair Dara Lindenbaum and Vice Chair Sean Cooksey—a Democrat and a Republican—provided a statement claiming that the commissioners reach bipartisan agreement in “nearly 90 percent” of enforcement matters.

“As Commissioners, we do our level best to work together and to enforce the law fairly and consistently. Without commenting on any specific case, Commissioners take each enforcement matter on its merits, and we reach bipartisan agreement in nearly 90 percent of them,” the statement said, without providing a timeframe or other context for that statistic. “Any narrative that the Commission is mired in deadlock or that its bipartisan structure prevents it from enforcing the law is misinformed.”

But “partisanship” can be sliced a number of ways. The FEC is required to have six commissioners, three Democratic appointees, three Republican, with four votes required for enforcement action. For a long time, one of the “Democrats” was an independent who typically voted with the Dems. But for more than a year under Trump, the agency didn’t have enough commissioners to attain a quorum, meaning enforcement matters couldn’t even be considered.

More to the point, the FEC’s own data shows that of all enforcement matters the agency voted on since 2019, the commissioners recorded at least one split vote in about 63 percent of them—meaning that in those votes, no position received the necessary support of four or more members. The data also shows that in 14 percent of those enforcement matters, all votes were split, including procedural votes in those matters. (Votes to close files were not counted.)

The large-scale logjam has dropped off this year, with a split vote appearing in 48 percent of enforcement matters, with just five percent of matters showing splits on every vote.

That shift in agreement can be attributed to Lindenbaum’s appointment restoring the 3-3 partisan balance. However, the new composition has also ruffled watchdogs, who have lived the “narrative” referenced in the commissioners’ statement and would appear to disagree vehemently with that statement’s spin. Two of the agency’s Democratic commissioners also seem to disagree with those claims, finding themselves on the opposite side of votes cast by Lindenbaum, who joined the agency last August.

Ghosh noted that the “ongoing divide” is about whether the agency fulfills its mission, not just which party the commissioners belong to.

“Certain commissioners simply do not appear to support the mission of the agency they were appointed to lead,” he said.

Ghosh appears to be referring at least in part to Lindenbaum, who upon her swearing-in has sided against her Democratic colleagues, Ellen Weintraub and Shana Broussard, in a number of enforcement matters. Most specifically, Lindenbaum—who unlike Weintraub and Broussard joined the commission without prior government experience—has voted with the three GOP commissioners to close deadlocked matters, robbing watchdog groups of a judicial end-around they had devised to bring unresolved investigations to federal court.

Ann Ravel, a Democrat who left the commission in early 2017, also disagreed with the commissioners’ statement, telling The Daily Beast that the FEC continues to fail in “matters of great importance” to democracy.

“The FEC, unfortunately, continues to rarely have the needed four votes to enforce the law in cases that have deleterious impact on democracy,” Ravel said. “Money in politics is one of the biggest ways that corruption in the political process undermines democracy. The FEC has failed to enforce the law in matters of great importance to the electoral processes.”

That trajectory would appear to be further codified in Dickerson’s recent proposal, which among other things would give commissioners more power over individual investigative steps.

Stephen Spaulding, vice president of policy at watchdog Common Cause, sharply objected to those new policies.

“To require line attorneys to seek four votes from commissioners for developments in their investigations, such as wanting to speak to a new witness—the commission already has a central role in providing supervisory guidance, they don’t need to micromanage, stepping into this role is unnecessary and would further create gridlock,” Spaulding told The Daily Beast.

HAC Democrats have some specific reforms in mind, all of which appear in the Freedom to Vote Act.

For one, in light of the commission’s ideological logjams, congressional Democrats would like to give more enforcement power to the FEC’s nonpartisan Office of General Counsel—the in-house legal investigative unit. Currently, the OGC can make recommendations about violations, and, when authorized by a majority of the six commissioners, the office can further investigate and deliver its findings. But Democrats would like to give the OGC the ability to take action against campaign finance violations, unless the commission votes to overrule that decision.

Another item on the enforcement wish list would be to engage the courts.

One measure would allow judges to review FEC dismissals, while barring the courts from considering claims of “prosecutorial discretion” as permissible defense for deciding not to take action on major violations—a sticking point among watchdog groups, as well. (A related reform would extend the statute of limitations on cases from five years to ten, depriving GOP commissioners of another common enforcement exit ramp.) Yet another proposal would allow private parties to bring civil lawsuits if the commission fails to act on a complaint.

Spaulding, of Common Cause, expressed hope that next week’s hearing won’t be as performative as the campaign finance hearings that the committee’s GOP members have presided over since acquiring the gavel in January.

“Committee Republicans have had a lot of show hearings, which have not been particularly substantive in many cases, but they’ve been using them to build a record to further dismantle campaign finance laws,” Spaulding told The Daily Beast, referring to the Republican-backed ACE Act. That bill, he said, would “add protections for more dark money in our elections and permit secret contributions to outside groups that are spending money in campaigns.”

He added that House Republicans appear “all too happy to see the FEC fail” at its enforcement mission.

“Some parts of the FEC are functioning really well. The resources and training they offer for candidates, and the administrative fine division, which has led to a dramatic reduction in late filings,” he said. “Unfortunately there are some major issues in the enforcement process that have broken down. That’s still concerning, but I’m hoping the oversight hearing will allow congress and the public to hear from the commissioners and get some reforms going.”