For all of the works of prose that focus on the subject of love—surely the greatest theme and mystery in literature—it’s curious how rarely authors get clinical about the subject. To break it down. To pin it to a dissecting tray, fold back the layers, and say, “see that part over there? That makes for skipped heart beats. This part here, that takes care of the arousal. This middle bit, that’s when you know you’re hooked.”

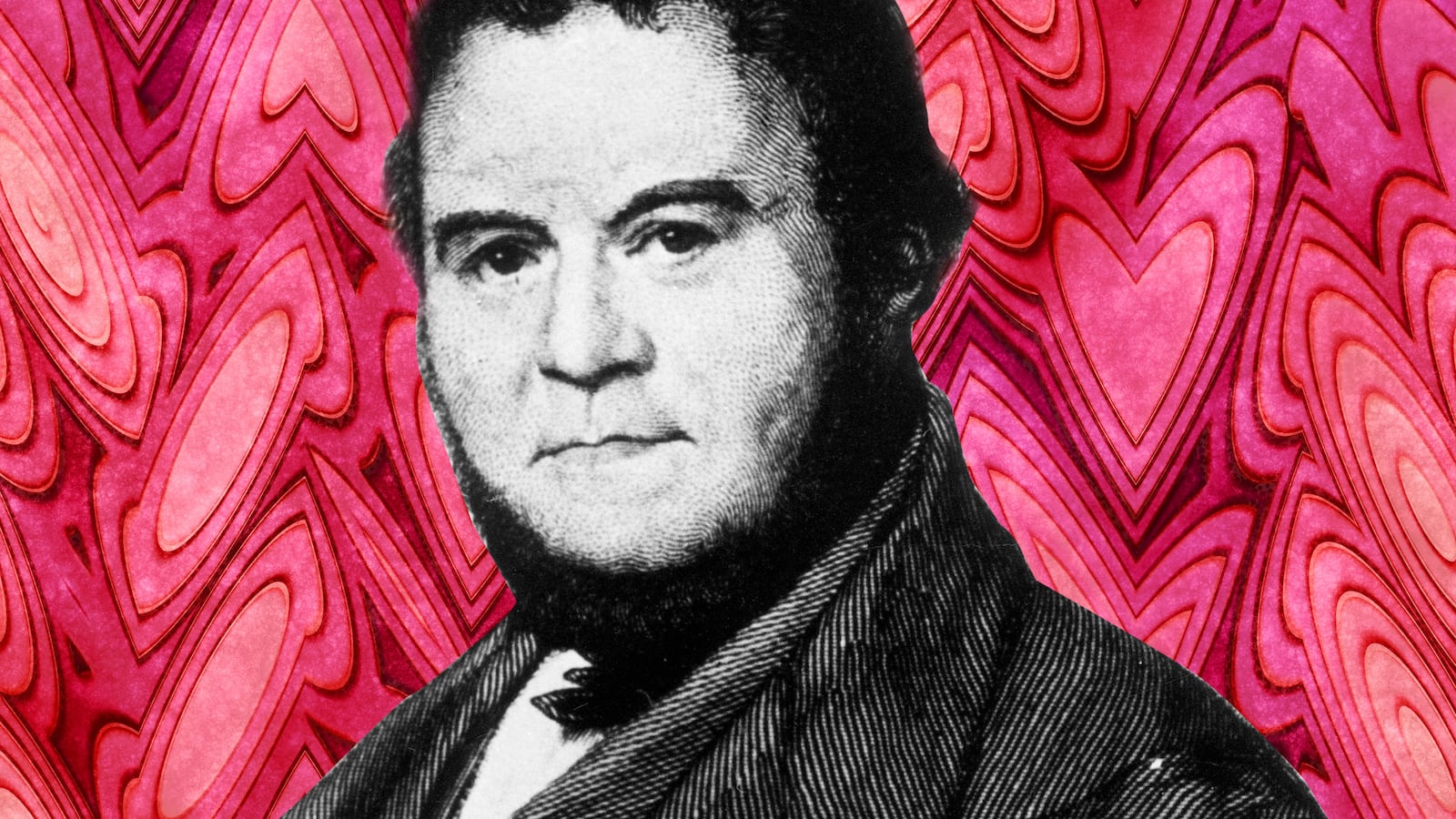

But if ever there was a born literary dissector, that would be the Frenchman Marie-Henri Beyle, better known as the novelist Stendhal. He went by a lot of different names in France in the first half of the 19th century, being King Pseudonym. He disliked his father, thinking he wasn’t creative enough, and doted on his mother, who died when he was seven.

He dug the military and the theater, serving in Napoleon’s army, engineering a rescue on a river that was much discussed, then sojourning in Italy where he picked up some dandified ways, which played well in Paris, where he went through woman after woman. You might say Stendhal dated serially; or you might say he had a thing for racking up sexual conquests.

Or, you might say he was gathering field notes, which, yes, sounds weird, but even as Stendhal objectified women and used them for his carnal purposes, he was coming to know a lot about them. Dating, if we are to call it that, became a form of research for him. He might have been a bit of a dick who always had his ready for you if you were of a comely stripe, but he wrote about women with his heart full for them, and he did so with nuance, grace, and kindness, while not stinting on his knowledge of what people of either sex could do to one another.

If you’ve read Stendhal, chances are it was with the novels The Charterhouse of Parma or The Red and the Black, both highly realistic fiction—he was one of the birthers of that movement—but with a Romantic’s high-grade sensibilities where one has the feeling that if a character were pricked, then the narrator of the work, the creator of its design, would bleed. His best male characters came to life because of their feminine sides. Sure, they could smite in wars, but you loved them best when they were vulnerable, when they aired how they felt and encouraged others to do the same—if by others we mean especially the one whom they truly loved.

Stendhal’s lifestyle caught up with him. He contracted syphilis, for which he took a treatment of iodine and quicksilver. His balls shrank, he could not sleep, his armpits swelled, he was tachycardic, and unable to hold a pen often. But he kept writing, kept searching, which is the core value of his strangest work, and the one I return to the most. I had read The Red and the Black in college, and of course I empathized with Julien Sorel, a romantic young man ready to conquer the world, ready to call out hypocrisy, standing against materialism. If you were virile and bookish, you’d love this character, and so I did. But I watched him getting pounded as he went along in the novel’s journey, his proverbial brains dashed on rocks like pike newly pulled from the brook, and I thought, “Yikes, boy has a lot to learn, and probably I do, too.”

It was then that I turned to On Love (1822), which Stendhal believed to be the best book he ever wrote. At the time, he was not yet 40 years old. He would go on writing for another 20 years. If you are 40 now as a writer, you are just getting started. The bulk of your writing career is in front of you. You are the prose version of a 25-year-old hockey player. But in the time of Stendhal, you were deep into grizzled veteran status, closer to the end than the beginning, often. You could pass for Parisian Yoda. Make no mistake: On Love is a book of obsession. The obsession to know why we love, how we love, when we start to love—this may have mattered more than anything to Stendhal—how we cease to love, how love changes us, and what love does to pair us with another while parting us from other things—ourselves sometimes, or reality.

Here’s a good rule for reading: If someone is a great writer, and they are obsessed about something and they compose upon that subject, run down that work. They’re doing it because they have something massive in their bosom that they believe really has to be in yours as well, for you to get max value from your life. It takes some doing for them to fully explain why that is and in terms such that you can never doubt it.

Van Gogh was an obsessive writer. He had knowledge that you had to know, ways of seeing you needed to be taught, and goodness how he labored at his sheets of paper in his mission. Melville was another obsessive writer. Do you think someone who wasn’t could have been so meticulous in all of that cetology business in Moby-Dick or with the whole of Pierre? In 1621, Robert Burton wrote a book we’d all do well to study during the depression-fostering age of the internet called The Anatomy of Melancholy. He deconstructs depression and anxiety, showing us each constituent part, so that we can better reorder ourselves in the attempted rebuild. I’m not sure if Stendhal read this book, but his On Love is a rejoinder, almost.

In 1818, Stendhal took a trip—for fun, like you might drive to New Hampshire and hike the Whites—to the salt mines of Hallein near Salzburg with his buddy Madame Gherardi. They went repeatedly down the 500-foot mines to see the white stuff—which must have been a possible metaphor in Stendhal’s brain—but what really interested him was what happened when a Bavarian officer started falling for the bewitching Madame G. As Stendhal would later write, he could actually see, just like one can see the rain falling outside, this fellow falling in love with his friend. He heard how his friend changed how she spoke about the officer, as she began to reciprocate the feelings. Flaws that had existed were groomed into something else, sometimes triumphs. The officer, meanwhile, had a hand fetish, apparently, because he couldn’t stop praising Gherardi’s hand, despite it being badly pocked with smallpox scars.

And Stendhal thought, “Hmmm, I should note this shit down.” If you went into those mines and you wanted to impress a girl, you got a tree branch, tossed it in the mine in winter, and retrieved it in the spring. By then it had been covered in salt crystals, the wood almost entirely eaten away, and you had quite the bijou to present to your lady love. Stendhal seized upon both the image and the process. They represented what it was like to fall in love. He called what happens to you, when you thus become forever changed because of how you feel about another, crystallization. Hat tip to the salt mines.

He wasn’t done with his road tested/sourced metaphors. A coach journey inspired him further: “When we are in Bologna, we are entirely indifferent; we are not concerned to admire in any particular way the person with whom we shall perhaps one day be madly in love with; even less is our imagination inclined to overrate their worth.” As he states, that is because crystallization has not begun in Bologna. But when we get to Rome, and all looks different? Well, bust out a spray of flowers and a fresh tube of KY.

It’s a four-step process, according to love’s master exegete. You started admiring the other person. They do something—maybe it’s a turn of phrase, maybe it’s how they pop a grape into their mouths—that causes some reconsideration. Then you acknowledge this to yourself. It’s the romantic equivalent of sitting back and thinking, “That’s interesting. Hadn’t noticed that before. Fair play.” That cycles through various permutations, and next you have hope that they’re thinking about you the same way. You begin to imagine designs that might impress them, that might make your feelings known without you having to have that go-for-it moment when you say, “Screw it! I love you! There! The truth is out!” Finally comes delight—this person could lance a blister in front of you, and you’d praise her healing hands of benediction, how lucent her face looked, as if she were an angel, even as she said, “Fuck that stings.”

In Stendhal’s view, your heart is as much another’s as your own at this point. But things also get tricky. When we’re having moments like that of the blister analogy, we are not seeing someone as they are. This doesn’t help us or them. What you want, naturally, is to see them fully in all the ways that make them them. And they do the same with you. And through each other, you come to see yourself, in all the parts you overlooked or misunderstood, better. You gain more of your identity, your actual identity, through their eyes, their care and concern, their vulnerability to you and yours to them.

Viktor Frankl defined love as a choice, a will to extend one’s self for another’s growth. It was, in his view, more about what you did for someone else, than what you got back. I buy this. I’m not someone who thinks we see someone and fall in love. As I’ve learned more in life, I’ve learned that, yes, everyone says I love you, but love is not common.

Infatuation is common, more and more so because of the attention it can bring back our way. You make a decision to love another, because you are plunging. You are leaving the cliff side, you are leaving the bathypelagic layer of the ocean behind for a deeper dive. Whenever we do something brave, we do not stumble ass backwards into it. We decide. We do emotional, spiritual, character-based math: Do I have the stuff to do this?

But that’s why Stendhal laid out his four-part process. A progression. He was by no means saying that this was the recipe for romantic happiness. He just wanted to say what normally happened in those times in our life, when we will be in love. And how many will we have? One? Two? Five? It’s not a lot, even if you make it to 100. And when we know what is happening, what is making us over so that we do love someone, we can check ourselves in some of the flaws of that process. When we see deficiencies as strengths in another, as the love besotted person often does, we are leaving reality. We’re helping the other person less well in their growth. When lovers romanticize everything, they can lose themselves. You stop being Person A and Person B who contribute to Relationship A-B, and you become this big, smeary, love amoeba, and who knows where each person begins and the other leaves off at that point?

The critics did not love On Love. They thought it bizarre. Self-indulgent. Stendhal was a funny bastard, but they didn’t like that either, as if he wasn’t always properly solemn, given his subject. They basically treated it like you treat that couple you see when you’re at the movies and he’s all over her and she’s all over him and you half-expect hot ropes of seed to go flying through the air before the trailers start. Get a room, right?

I think the critics were embarrassed by the book. I don’t think Stendhal cared any more than two lovers ever have about people tut-tutting over their public displays of affection. I don’t think he even noticed. I think he loved what he found in his mind, and he had a relationship with that now, and that was his heart’s embrace at the moment.

You may now wish to ask who was the great love of Stendhal’s life. That would be Mathilde, Countess Dembowska. He met her when he lived in Milan. And try though he might to pass the salt-encrusted bough to her, she never loved him back. Would he have written On Love if she had? Sometimes you need to lose—or never have—to really know what you want. Ah, but I bet you know that, don’t you? For such is love.