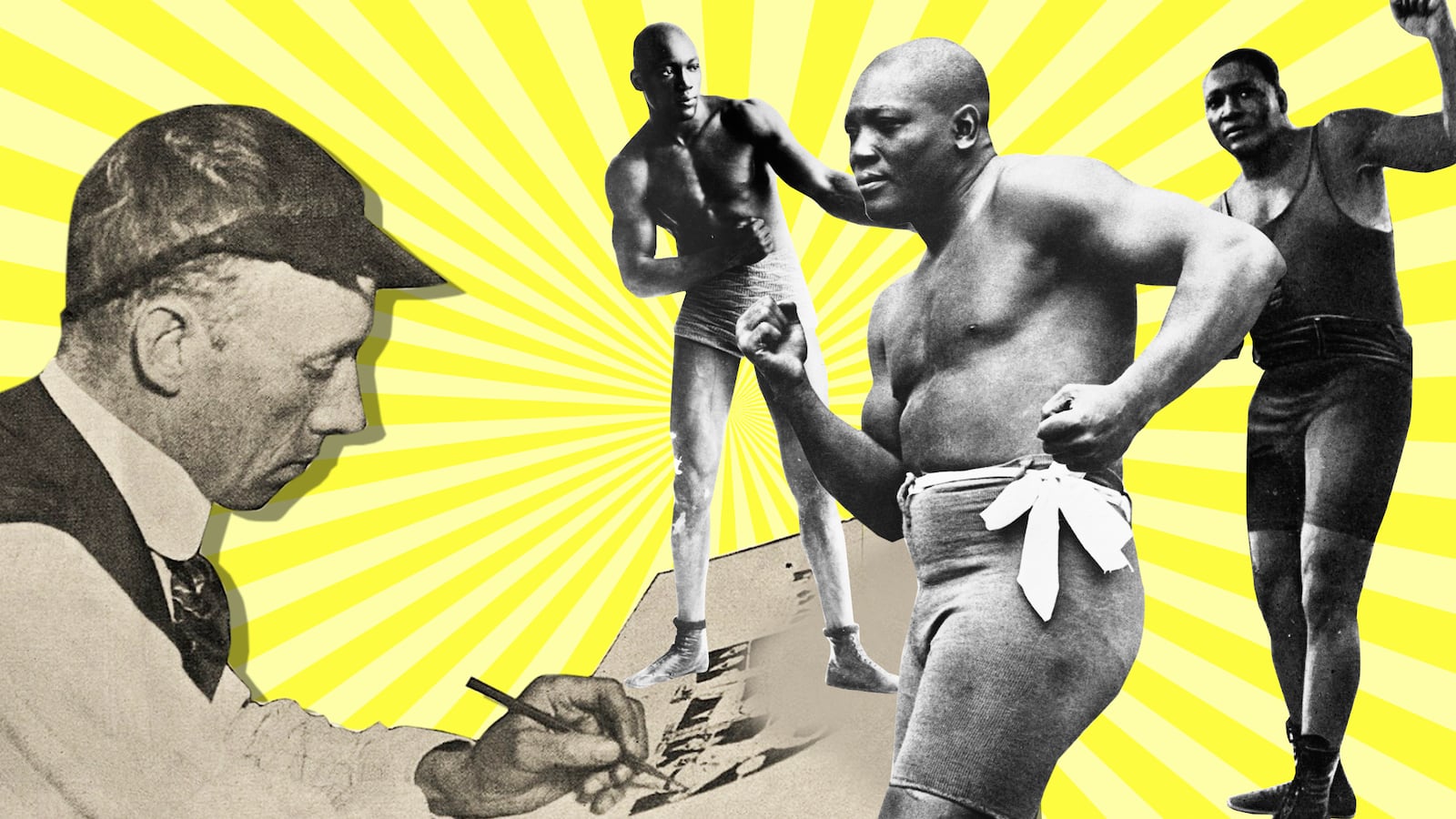

The friendship between the fighter and the cartoonist lasted for nearly thirty years. It was as influential as it was unlikely, with neither boxing nor cartooning ever being quite the same.

The fighter, Jack Johnson, was born in Galveston, Texas in 1878. He was a child of former slaves. Johnson worked at the docks and at racetracks until he discovered boxing. Then he fought his way to becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. Because he defeated white boxers on his way to the crown, he was regarded as the most hated man in white America.

The cartoonist, Thomas Aloysius “Tad” Dorgan, was born in 1877—one year earlier than Johnson—to a family of poor Irish immigrants in San Francisco. When he was a kid, all he wanted to be was a boxer. That dream ended when his right hand was crushed in an accident. He found his way to cartooning and writing and became one of the most beloved sports journalists of the past century.

Ted Dorgan

Their friendship began in 1901 and didn’t end until Dorgan died in 1929. Its greatest test came in 1910, when Johnson, then world heavyweight champion, was in a contest with a former champion to hold onto the crown. His opponent, Jim Jeffries, was white, and following Johnson’s victory, jubilant black fans would be attacked and even killed in cities across the country.

The victory in the boxing ring would also mark Johnson in the eyes of the law. Yet for Dorgan, watching from ringside as his smiling friend sent Jeffries into the ropes, it was a reminder of all the reasons why he admired this man, and why that morning he had delivered one of the most startling sports predictions ever offered in print:

“Jim Jeffries is through.”

It would be nearly impossible to overstate the audacity of the prediction that awaited readers of William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers on the morning of July 4, 1910.

Jeffries had been coaxed out of retirement by fight fans desperate for a muscular symbol of white supremacy in post-Reconstruction America. The leader of this effort had been the writer Jack London, who in the New York Herald argued that Jeffries owed it to his race to emerge from his alfalfa farm to wipe off Johnson’s brilliant smile. “Jeff, it’s up to you,” London pleaded.

At the time, Jeffries was three hundred pounds and nearly thirty-five years old. Finally he was persuaded by a hundred-thousand-dollar purse, and set out to get himself down to something resembling fighting form. Around the country, newspaper readers eagerly following each day of his training. But it amounted to a national delusion — and no writer has ever recognized self-delusion better than Dorgan. On the ominous Fourth of July in Reno, Nevada, long before the first blow landed, Dorgan confronted his readers’ racism head-on. “The public is just beginning to see that this black man is a great fighter,” Dorgan wrote of Johnson. “He was held down for years on account of his color.”

Dorgan acquired his bare-knuckle honesty growing up in a section of San Francisco marked by “factories, slums, laundries, machine-shops, boiler-works and the abodes of the working class,” wrote Jack London. It was a “Fighting World,” as Dorgan would later title a cartoon for the San Francisco Bulletin. Accordingly, his first wish was to be a boxer. “When I was a kid I followed John L. Sullivan and Jim Corbett along the streets of Frisco full of admiration and wishing that some day I could lamp a real fight,” he later said.

This wish was dashed when Dorgan was five years old. He was playing around some workers who were moving a house, and somehow the boy’s right hand became caught in the windlass rope, tearing off four fingers. Dorgan’s father sued for $25,000 and settled for a thousand, and young Tad had to switch dreams.

His new idol became a cartoonist named Jimmy Swinnerton, who worked for William Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner. Swinnerton was the creator of the comic The Little Bears, a riff on the emblematic California bear. “Then I used to follow Jimmy Swinnerton in that same town,” Dorgan later said. “I longed to be artist, and there I was with that nub of a mitt.”

Dorgan taught himself to write and draw with his left hand and, after a stint in art school, landed a job at the Bulletin. He worked his way up from office boy to staff cartoonist, drawing everything from politics to sports cartoons. It was during his time at the Bulletin that he first met Jack Johnson.

It was December 1901. The previous year in Galveston, Johnson had knocked out his first white opponent and, with his family, survived a devastating hurricane, according to Geoffrey C. Ward’s authoritative biography, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. Johnson began travelling for fights, including a bout in California. On that visit Johnson first glimpsed Jeffries—and Dorgan first glimpsed Johnson.

Dorgan had joined others to witness a training match between Johnson and a Brooklyn boxer named Kid Carter, who was preparing for an upcoming fight in San Francisco. Johnson had been hired as a sparring partner. He would quickly chafe at being cast the supporting role.

“On the Sunday before the fight, a delegation of sporting men from Frisco… visited Carter’s camp to give him the up-and-down,” Dorgan later wrote in an introduction to Johnson’s memoir, Jack Johnson: In the Ring and Out. “After the usual gym training, Carter put on the gloves with Johnson for a four-round workout. In the third round of the affair, Johnson hit the boss a bit harder than a sparring partner is supposed to sock his paymaster and Carter got mad.

“‘Trying to show me up, eh?’ he growled. He lowered his head and tore into Johnson.

“‘I’ll show you who the boss is around here,’ he added.”

The loaded word “boss” did not exactly calm Johnson. Dorgan watched in astonishment, Carter tried and failed to put Johnson away, Finally, the promoter stepped in to avoid losing his boxer before his big bout. Not surprisingly, Johnson lost the job. But, Dorgan recalled, he was all anyone wanted to talk about on the way home.

“That was Jack Johnson’s start in the city by the Golden Gate,” Dorgan said, and it was also the beginning of Dorgan and Johnson’s friendship.

Johnson and Jeffries signing papers to fight with Tad in the background.

“I see Tad as something of a scrapper, verbally at least,” cartoonist Eddie Campbell says. “One feels that these fighters saw Tad as a like soul.”

Best known for his collaboration with Alan Moore on the graphic novel From Hell, Campbell this year published The Goat Getters: Jack Johnson, the FIGHT of the CENTURY, and How a Bunch of Raucous Cartoonists Reinvented Comics, a revelatory history of early sports cartoons.

Until Campbell’s book, Dorgan’s work has rarely been available in print. Of course, Dorgan was not working for posterity. Like the fighters he drew and admired, his first concern was making a living. This became more critical just days after he attended Johnson’s sparring session, when his father suffered a stroke and died, leaving behind Tad Dorgan. his mother, and his ten younger siblings.

“There wasn’t a lot of money there and it was a big family,” Tad Dorgan’s grandnephew, Richard Dorgan, says. “They lived by their wits and it paid off. Tad kind of took over and led the way, they all ended up on the East Coast in New York.”

Dorgan started working for Hearst in 1904 and was quickly sent to the front lines of Hearst’s political battles; early assignments included caricaturing Tammany Hall boss Charles M. Murphy in an infamous cartoon of Murphy in prison stripes. It’s a work that even received a mention in Citizen Kane, Orson Welles’ classic movie based in part on Hearst. “I wouldn't show him in a convict suit with stripes—so his children could see the picture in the paper,” a political boss admonishes Kane.

Dorgan clearly preferred the sports page over politics. There, he could work with a remarkable degree of independence, even publishing cartoons and writing that ran counter to the newspaper’s official positions. While Hearst editor Arthur Brisbane inveighed on the opinion page against drink and debauchery, Dorgan celebrated both of these activities in the sports section, employing what humorist S. J. Perelman later called a “wink and a leer.” When Brisbane thundered against boxing, Dorgan celebrated its near-mythic heroes, creating a type that Eddie Campbell calls the “blue-collar Hermes.”

Dorgan’s work stands out for its originality—even during cartooning’s most original era. He lampooned the 1907-1908 murder trial of Harry Thaw with a series about a dog named Bunk on trial for murdering frankfurters. He featured more dog characters in comic strips such as Silk Hat Harry’s Divorce Suit and Judge Rummy, which were later adapted into animated cartoons. Another Dorgan comic, titled “Daffydills,” was little more than stick figures spouting witty lines, yet it was somehow adapted into a Broadway play.

Yet today, if Dorgan is remembered at all, it is as a creator of slang. When Funk & Wagnalls’ president Wilfred J. Funk created a list of the “ten most fecund makers of American slang,” he put Dorgan at the top. Dorgan is credited for “the cat’s pajamas” and “the cat’s meow,” for all-purpose insults such as “dumb dora” and “dumbbell,” and “cheaters” for glasses and “hard-boiled” for tough. Modern characters like lounge lizards and drugstore cowboys are also said to be Dorgan inventions. So is Vice President Joseph Biden’s favorite word “malarkey.” The jazz-age phrase “Yes, we have no bananas” was seen in a Dorgan cartoon before it became a popular song.

“Slang affirms a freedom of the spirit and the democratic idea that language belongs to everybody, to be increased by any citizen who can invent a phrase and make it stick,” Eddie Campbell writes in The Goat Getters. It clearly is this same freedom of spirit that connected Dorgan and Johnson. Scenes of their friendship are rare, but in his research, Campbell located an interview with Johnson that was conducted by writer and artist Kate Carew just prior to the fight with Jeffries. Dorgan is in the room for the interview, as well. Carew comments on how a joking Johnson would dig Dorgan in the ribs. Then she adds, “Were any rash person to make a hostile movement toward Tad in Mr. Johnson’s presence—gracious! I tremble to think of the consequences.”

In Unforgivable Blackness, Geoffrey C. Ward correctly notes that “Johnson was the subject of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of newspaper cartoons during the course of his career… Johnson looks the same in virtually all of them: an inky shape with popping eyes and rubbery lips, by turns threatening and ludicrous.”

In early comics, such inky shapes would often serve as warped likenesses of African Americans—including in many Tad Dorgan cartoons. Even his one-panel masterpiece “Indoor Sports,” a sharp and acerbic look at human behavior, was not immune.

A typical “Indoor Sports” might feature a couple of lead players in the foreground acting like fools or hypocrites, or both. Behind them, a chorus of onlookers laughs hysterically, their mouths opened like half moons. “Tad’s ‘Indoor Sports’ comics always show two groups of people: Those who behave badly or stupidly, and those who observe knowingly and comment on the foolish behavior,” Peter Huestis, a staff member of the National Gallery of Art and collector of Tad Dorgan art, says, adding that “African Americans are always depicted as being in the latter group.”

A sports page with a Tad cartoon of Johnson

Yet however shrewd and sardonic, blacks in “Indoor Sports” are also virtually indistinguishable from each other in appearance. This is also the case in many of Dorgan’s sports cartoons, including those of Johnson. In these newspaper works, Dorgan failed to rise above the visual conventions of his day. Yet another group of Dorgan’s cartoons are startlingly different. These include intimate portraits of Johnson, remarkably absent of any trace of racist caricature. Among these is “Champion Jack Johnson Before, During and After the Battle,” which appeared in Hearst newspapers on July 5, 1910. A series of four close-ups of Johnson’s face trace his state of mind from ferocity to relief.

An even more remarkable—even revolutionary—cartoon shows Johnson in training for his fight with Jeffries, running alongside the spirits of past white champions. He is depicted as both their equal and their heir. Here Dorgan crossed cartooning’s color line just as surely as Johnson punched his way over the one in boxing. Implicit in each crossing is an invitation for others to follow.

According to one onlooker, Jack Johnson had more than encouragement from Tad Dorgan during his fight with Jeffries. “I was at the ringside at Reno when Jeffries was whipped,” said the New York Journal’s Harry McCaffrey. “He and Tad Dorgan, our artist, were at loggerheads and Tad did everything to get Jeffries’ goat and succeeded mighty well.”

Johnson needed no help in Reno, however, and his decisive victory only further enraged white boxing fans who were denied their symbol of a supreme being. After violence erupted across the country, concern began to grow about films of the fight that were set to show in theaters. William Randolph Hearst helped lead a campaign to have them banned. Meanwhile, on the sports page, Tad Dorgan reviewed the films, calling them “the best pictures ever shown here, and that’s saying a great deal.”

It went like this for some time. Hearst’s newspapers might announce “Johnson a disgrace to country,” describing the boxer as having a “vain and twisted child’s mind in the body of a great fighting brute.” Meanwhile, Dorgan continued to write about the boxer with only respect and admiration of his “punching power and ability to finish a man after he gets him going.”

In 1912, Johnson was arrested for violating the “Mann Act,” because he drove with his white girlfriend across a state line for allegedly “immoral purposes.” He fled the country and fought overseas, finally losing to white boxer Jess Willard in 1915. Dorgan wrote of his shock that his friend, the “master boxer, kidder and hitter,” had finally lost the championship. Meanwhile, Willard clearly set himself apart from Johnson, declaring, “I want to be a popular champion.”

Johnson returned to the United States in 1920 to serve out his term in Leavenworth Prison in Kansas. This year, he was posthumously pardoned by President Donald Trump after being urged to do so by Sylvester Stallone, who is launching his new Balboa Productions with a biopic about Johnson. (The pardon, as Jeet Heer wrote in The New Republic, was rife with ironies, not the least of which was that on the same week Trump pardoned Johnson, he told black athletes who protested police brutality during the National Anthem that they didn’t belong in the country.)

A self-portrait by Tad Dorgan

Also in 1920, Tad Dorgan suffered a heart attack that curtailed his sporting life. From that point on, he was largely confined to his home in Great Neck, New York. Occasionally, his brother Ike and wife, Izole, would drive him to an upper-floor window over Broadway. “That’s close enough to the mob for me now,” Dorgan said. “I lamp the cake-eaters with their dolls, the blind musician singing along Thirty-fourth Street, the busy guys, the easy-going guys, the old dames with their accordion-pleated chins, the gyps and the square shooters. I get a wallop out of figuring their graft from my high perch.”

Unable to attend any sporting events, Dorgan relied on two young assistants to report back from baseball games and boxing matches for his drawings. As one last joke on his plight, he datelined some of these works with the names of cities around the world.

It’s not likely Dorgan and Johnson spent much time together during those difficult years. Yet they stayed in contact. 1929, Johnson penned a series of newspaper columns about his various boxing matches. He said he couldn’t have done it without Dorgan’s help. “Day after day… I would call Tad on the phone and ask his advice and opinion as I laboriously constructed my thoughts and whipped them into newspaper shape,” Johnson remembered.

Dorgan was eager to read the whole series but Johnson held him off, telling him he had to wait until they appeared in print. He would regret that decision when he learned of Dorgan’s death. He scrapped his plans for the final column and finished the series with a tribute to Dorgan and their friendship. He wrote about how Dorgan gave him his nickname, “Li’l Artha,” after Johnson’s middle name. He wrote about how all sports writers should find a moral in Dorgan’s life. He wrote about how Dorgan was a great fellow who either liked you or didn’t want any part of you.

“And he was the one writer who always asked for a fair deal for me,” Johnson remembered. “He gave me credit for everything I did and although many men tried to split us apart, Tad always stuck to me.”