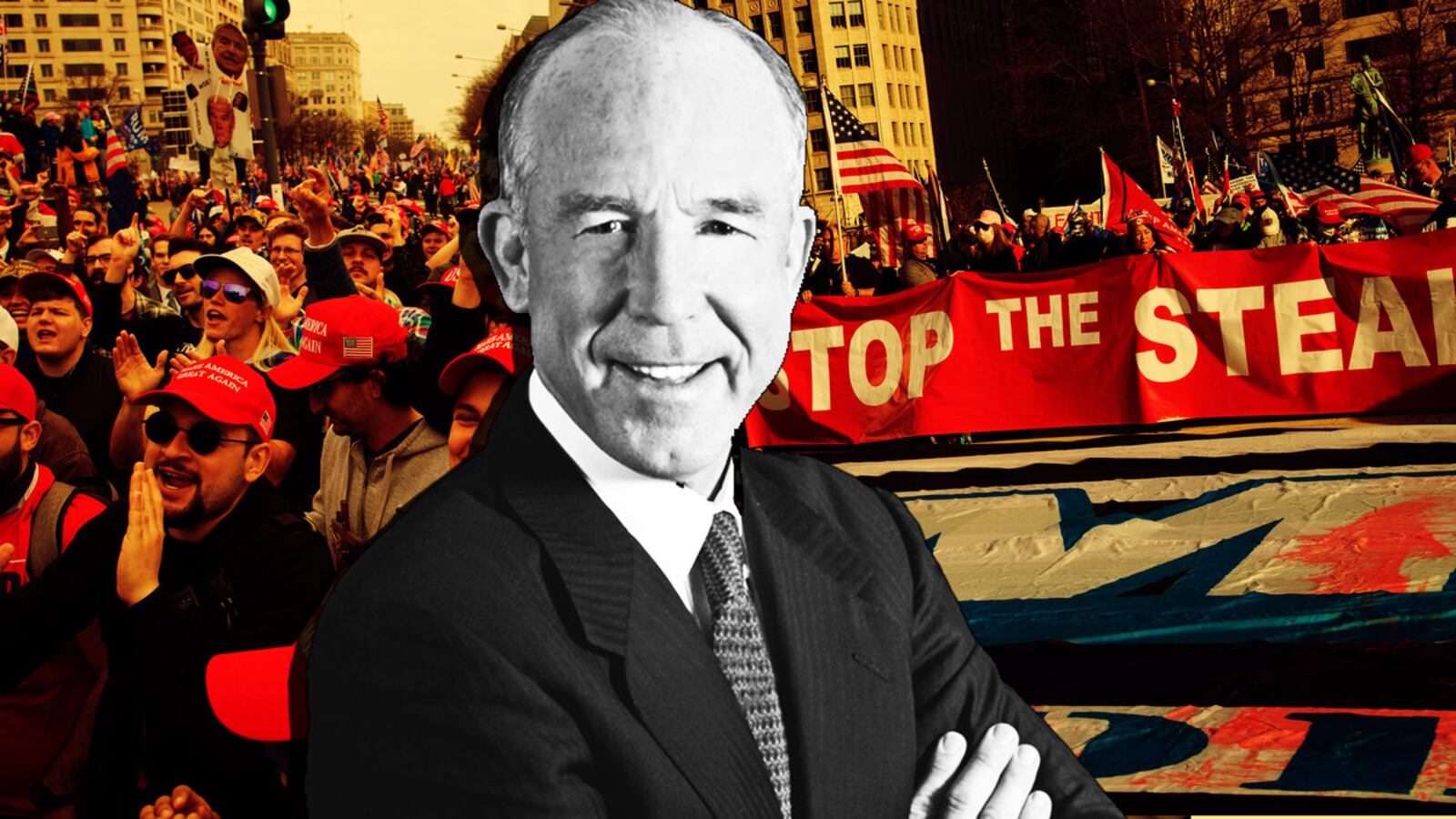

Last fall, as Donald Trump promoted fears about widespread election fraud and pressure mounted on Texas Republicans to prevent the state from going blue, local GOP kingmaker Dr. Stephen F. Hotze became convinced that the far-right John Birch Society’s long-ago warning of a communist takeover was on the verge of coming true.

Hotze warned his wife to prepare for a left-wing revolution. And, using a fortune he amassed as a “hormone replacement” doctor, he began paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to a small army of private investigators, dead-set on proving his claims that Houston Democrats were committing voter fraud on a massive scale.

Hotze’s private investigators tracked the movements of specific people in the city who he suspected of committing crimes. In a blog post, Hotze claimed that his investigators were working 15-hour days and cost $200,000 a week.

“We’ve uncovered a massive voter election fraud scheme in Harris County,” Hotze said in an Oct. 14 video. “We have 20 investigators on the ground that will be working between now and Election Day.”

Hotze’s plan blew up five days later in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 19, when one of his private investigators, former Houston Police Department captain Mark Aguirre, slammed his SUV into a box truck driven by air-conditioning repairman David Lopez-Zuniga.

According to an account Lopez-Zuniga later gave to local TV station KPRC, Aguirre feigned injury after the crash. And, as Lopez-Zuniga approached to help him, Aguirre allegedly pulled a gun, disengaged the safety, and aimed it at Lopez-Zuniga’s head.

Aguirre appeared convinced that Lopez-Zuniga’s truck was filled with hundreds of thousands of illicit ballots cooked up by Hispanic children in a scheme funded by nearly $10 million from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. When he approached Lopez-Zuniga, he allegedly ordered him to the ground at gunpoint, as his associates drove away with the box truck. When police arrived, Aguirre laid out the byzantine tale and pleaded to their political sensibilities.

“I just hope you’re a patriot,” Aguirre told the police officer interviewing him, according to a police report.

Except, Aguirre was wrong. Houston police found Lopez-Zuniga’s truck, which was filled not with ballots but with air-conditioning repair equipment. Nevertheless, the next day, the Liberty Center for God and Country, a group run by Hotze, wired $211,400 to Aguirre’s bank account.

Mark Aguirre is a former Houston Police Department captain who worked as a private investigator for Dr. Stephen Hotze.

Houston Police DepartmentAguirre was arrested and charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon on Tuesday, nearly two months after the crash.

But Aguirre isn’t some lone-wolf vigilante. Instead, his arrest marks a dangerous collision between reality and a well-funded private surveillance network helmed by a Texas Republican power broker addled by conspiracy theories. It also shows the perils that can come when political paranoia is fed by sources as powerful as the president—in this case, manifested in the form of a gun pointed at an innocent person's head.

Hotze and his lawyer, former Harris County GOP chairman Jared Woodfill, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Hotze first broke into Texas politics in the 1980s as a rabidly anti-gay Republican activist, pushing an referendum in Austin that would make it legal to discriminate against LGBT applicants in housing. After that failed, he helped to block a measure that would make it illegal to discriminate against gay applicants for city jobs in Houston, and later led a slate of anti-gay Houston politicians who dubbed themselves the “Straight Slate.” By the early 1990s, Hotze had enough power to lead a splinter faction of the Harris County Republican Party based around his hardline stances on gay rights and abortion.

How Hotze came to have such political influence is owed to the wealth he amassed. And the wealth he amassed was due to the “hormone replacement” medical practice he operated. But, here too, Hotze’s record has come under fire.

He’s claimed that men who have lost their testicles because of medical issues later struggle to solve math problems and "have difficulty reading a map.” When Hotze appeared on CBS in 2005 to promote his ideas about hypothyroidism, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists responded with a letter to the network blasting Hotze’s ideas as “scientifically erroneous” and “readily refuted by a large body of solid scientific evidence.”

In 2018, a California environmental group sued Hotze and his companies, alleging that Hotze nutritional products with names like the “My Hotze Pak Skinny Pak” and “Bodyworks Plus by Dr. Hotze” exposed consumers to undisclosed amounts of lead. The case is ongoing.

And yet Hotze remains a powerful figure in Texas’s religious right, becoming a close ally of Dan Patrick, the Republican lieutenant governor, arguably an elected office more powerful than the governorship itself.

Even as many politicians distanced themselves from earlier attacks on gay rights, he kept them up. In 2015, he claimed that the legalization of gay marriage would result in kindergarteners being “encouraged to practice sodomy.” In 2016, he compared LGBT people to termites who “eat away at the very moral fabric of the foundation of our country.”

Hotze is also an ardent promoter of conspiracy theories, pushing QAnon claims about tens of thousands of sealed indictments prepared for a mass arrest of top Democrats. In Facebook posts first reported by Media Matters, his Liberty Center claimed that the COVID-19 pandemic is part of a “global ritual” to “inject experimental nano bots and chemi-kills into our bodies to alter our DNA using Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology to turn us into zombie-like, controlled masses and weapons of war.” In a June call to Gov. Greg Abbott, he asked the governor to order that rioters be shot. “Kill ‘em,” he said.

Dr. Stephen Hotze, attending an anti-mask demonstration in June, grabs a counterprotester’s sign before ripping it up.

KPRCHotze officially created his Liberty Center for God and Country to “promote and protect our God-given, unalienable Constitutional rights.” And, at first blush, it can look like a fairly standard religious conservative organization. In practice, though, the group serves as a clearinghouse for Trumpian political views and for promoting his lawsuits.

Those lawsuits are often in support of conservative causes. But they’re also overtly political. In the lead-up to the election, Hotze made a failed attempt to get 120,000 ballots cast at drive-in voting locations thrown out—an effort at 11th hour voter disenfranchisement that shocked most other observers.

But while the attention days before the election was on what Hotze was doing in the courts, his crusade against imagined voter fraud was also playing out on the streets.

In October, Aguirre and private investigator Mark W. Stephens met with fellow PI Wayne Dolcefino at Dolcefino’s office. Dolcefino, a former local TV news reporter who has rebranded himself as an investigator and media consultant, said Aguirre and Stephens wanted to use his status as a local political “influencer” to promote their allegations about voter fraud.

But even as they promised to show Dolcefino video and audio proof of voter fraud schemes in the county, the two investigators working for Hotze never provided it.

“Where this thing went off the rails, I have no idea,” said Dolcefino, who says he wasn’t a part of Hotze’s investigation.

Dolcefino described Aguirre as a “media-friendly” person who “likes to cause some drama.” His involvement in Hotze’s investigation into voter fraud made sense, Dolcefino said, in that Hotze wanted private investigators who would be amenable to looking into his pet causes.

“They went to like-minded folks who generally are on the conservative side of the agenda,” Dolcefino said. “Aguirre’s more of what I describe as a mercenary guy.”

As a police captain in 2002, Aguirre led a raid on a street racing event outside a Kmart parking lot that netted 278 arrests. The raid grabbed headlines in the city for days, but Aguirre’s publicity quickly soured after none of the people arrested actually faced street racing-related charges. The charges were later dropped amid allegations that police had arrested Kmart and Sonic drive-in customers who had nothing to do with street racing, with a federal judge calling the raid “almost totalitarian.” Aguirre was acquitted on criminal charges over the raid and resigned from the department ahead of his expected firing.

Accounts of how much money Hotze’s Liberty Center paid to Aguirre and the other investigators vary. Liberty Center wired a total of $266,400 to Aguirre’s bank account over a one-month period in September and October, according to a Houston police report. But it’s not clear whether that money was for Aguirre alone. At a Wednesday press conference, Hotze claimed he had paid the investigators “closer to $300,000.” And in an Oct. 14 media appearance, Hotze claimed his budget for the investigators was more than $600,000.

Whatever Hotze paid the investigators, both he and his crew were open about surveilling prominent figures around Houston, including Houston businessman Gerald Womack. Without offering any evidence, Hotze alleged that Womack was involved in a wide-ranging ballot-rigging scheme.

“We surveilled his office,” Hotze said in an Oct. 20 appearance on a show hosted by Republican pundit Alan Keyes. “As he came up, he looked slowly in every car. He knows he’s being watched, he doesn’t know who’s watching.”

Hotze discussed his surveillance on a show hosted by Alan Keyes.

IAMtvThe Houston Business Connections newspaper, a publication that served as a vocal booster of Hotze’s investigators, even published pictures of Womack’s office and cars around it, urging average citizens to report anything suspicious.

“They had surveillance on several individuals, not just the repair guy,” said Aubrey R. Taylor, the publisher of the paper.

Hotze boasted about his surveillance team even after Aguirre allegedly pulled a gun on an innocent man. The doctor claimed his investigators were tracking nursing homes and other locations where they claimed voter fraud was occurring.

“We have 20 investigators,” Hotze said in a TV appearance on Oct. 20, a day after Aguirre’s crash. “They’re following, they’re surveilling, they’re going to nursing homes, they’re going to the homeless centers. They’re going to the neighborhoods.”

It’s not clear how Hotze’s investigators became fixated on Lopez-Zuniga. The Daily Beast talked to three people who were familiar with Hotze’s operation when it was taking place and generally sympathetic to its goals, but said they had never heard of Lopez-Zuniga or the idea that Mark Zuckerberg was funding an operation where Hispanic children faked ballots.

Hotze didn’t mention Lopez-Zuniga or the supposed fingerprint plot in his frequent social media posts. Taylor, whose small paper served as a sort of running commentary on the private investigators’ escapades, never wrote about it.

Aguirre’s own lawyer, Terry Yates, described the crash as a “minor altercation” that “escalated” and said prosecutors wanted to turn Aguirre into a “scapegoat.”

“They didn’t think he was an AC guy,” Yates said. “I believe they thought he was involved in a ballot harvesting scheme.”

At a bizarre press conference on Wednesday, Hotze told reporters that Aguirre’s charges were “political retaliation” from Houston’s Democratic district attorney, whom he accused of being in on the ever-expanding ballot conspiracy. And though he had shelled out hundreds of thousands of dollars to find air conditioners, not ballots, in the back of Lopez-Zuniga’s truck, Hotze seemed utterly undeterred.

“Of course there’s election fraud in Harris County!” he said.