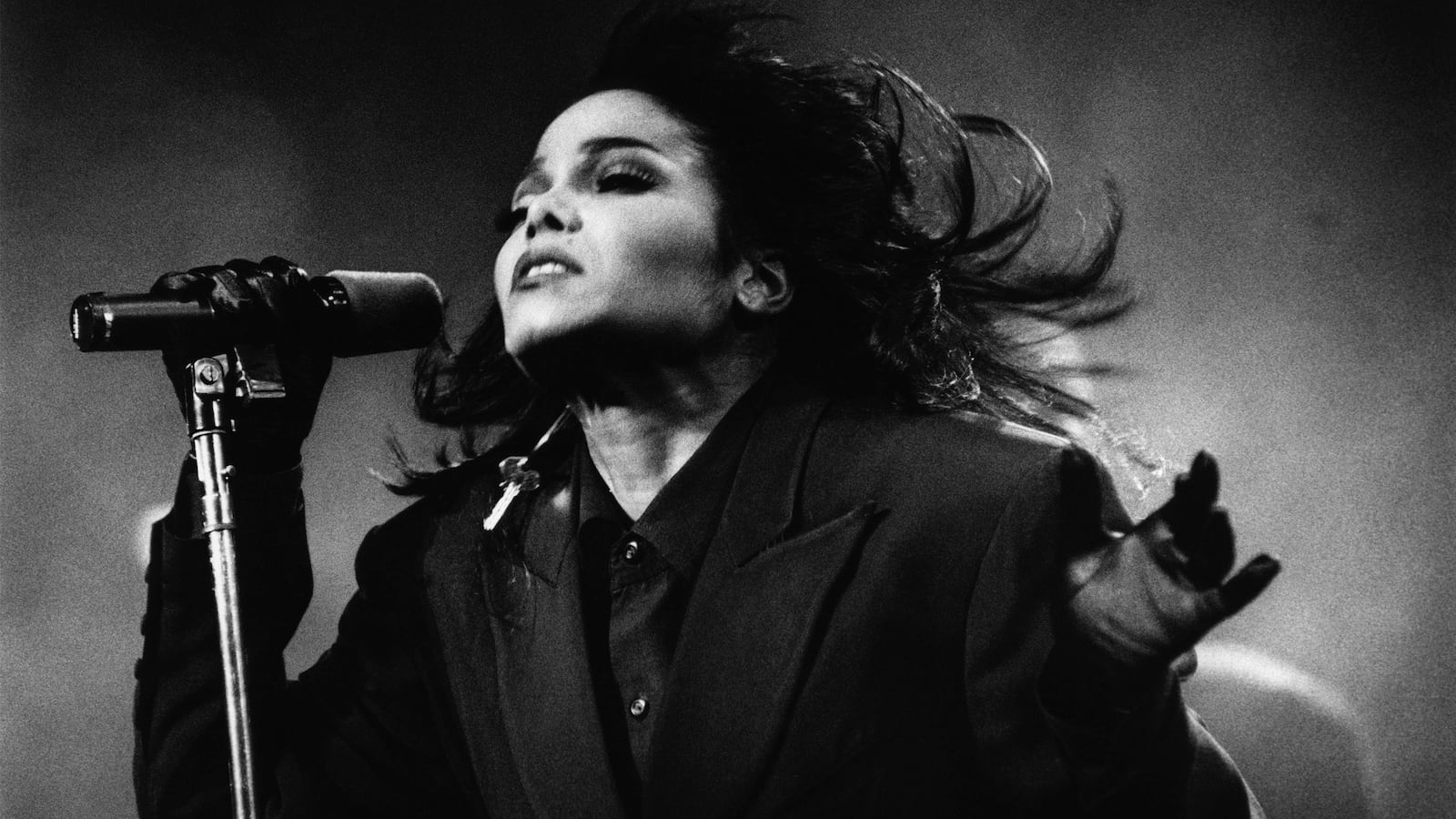

Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 is a blockbuster and a landmark album—for Janet, for producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, and for its time. It has sold 12 million copies and famously spawned a whopping seven Top 5 hits, but the legacy of Rhythm Nation is deeper and darker than its commercial success. The catalyst for Jackson’s magnum opus was a moment in U.S. history that would come to herald a harsh, ugly facet of contemporary American life.

“I remember when we were working on Rhythm Nation with Janet, and we had this concept for a song… We were watching CNN and there had been a school shooting and all these kids had been getting killed and we just thought, we gotta talk about that on a record,” remembered Jimmy Jam.

It was Jan. 17, 1989, when white supremacist Patrick Purdy murdered five children and wounded 32 people—mostly Southeast Asian refugees—at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California. The tragedy would shock the nation, and occurred just a decade after the similarly-named 1979 Grover Cleveland Elementary School shooting in San Diego, California, when 16-year-old Brenda Spencer opened fire on schoolchildren from her apartment window. The Stockton shooting was particularly devastating for the mostly Vietnamese and Cambodian student body and community.

“When this happens, as far as a school, it’s not your child who’s been killed,” former Cleveland Elementary School second-grade teacher Julie Schardt said in 2013, recalling that fateful day. “But it’s one of the children you are responsible for. You are the main nourisher. You give them sustenance. Especially in primary—you are a parent. In loco parentis. You’re a counselor. You feed them. You’re a nurse. All of those things.”

Schardt was one of the teachers that had to identify bodies in the immediate aftermath of the carnage, and never forgot seeing the body of her 8-year-old student, Oeun Lim. “It was such a surreal experience. I remember it was cold, and I remember her red shoes.”

It was this horrific incident that inspired Janet Jackson’s topical fourth album Rhythm Nation 1814. A concept album from the production/songwriting duo Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, it remains a standout for Janet. Coming on the heels of the monstrous success of Control—an album that produced five Top-10 singles and landed a nomination for Album Of the Year at the 1987 Grammys—there were high expectations and tremendous pressure for what the youngest Jackson would do for a follow-up. A lot had changed in popular music: the rise of dance-pop divas like Jody Watley and Paula Abdul led to whispers that Janet had been usurped; the emergence of new jack swing had dominated black music in 1988 and into 1989, making the slick, classic Minneapolis sound-inspired gloss of Control seem like yesterday’s news; and perhaps most significantly, hip-hop was suddenly at the forefront of black music and culture, with Public Enemy’s magnum opus It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back courting commendation and controversy by giving voice to black rage at the end of the Reagan era as crack, guns, and the 1990s loomed.

A young girl wounded in the chest during the shooting at Cleveland School by Patrick Purdy, being attended to by medical personnel.

Michael Chow/The LIFE Images Collection via GettyWith so much shifting in black music, Janet Jackson sought to do something more ambitious than a collection of catchy singles about how grown up she was. Working elbow-to-elbow with Jam and Lewis, they would take the conceptual approach of Nation of Millions and marry it to the hard-hitting brand of new jack swing Jimmy and Terry had showcased expertly on New Edition’s Heart Break album in 1988. This wasn’t going to be a Control sequel, and Janet’s approach to the album was not without hurdles.

Before the project could even get off the ground, her adviser and unofficial manager, A&M’s Director of Urban Music John McClain, complicated things. McClain had guided Janet’s career following the disappointing reception to her first two albums, helping to propel her Control breakthrough. But while the label didn’t want Jackson to buck the formula that made Control work, there was the contradictory issue with McClain, who also didn’t want to pay Jam and Lewis for work on a follow-up. He started Janet on a project with new producers, but the star recognized the potent chemistry she’d had with Jam and Lewis, and cut ties with McClain as her manager before convincing A&M to bring Jam and Lewis back on board. And she wasn’t interested in rehashing the themes of maturity and independence that had defined her breakthrough album—not with Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing still in theaters and political hip-hop forcing tougher conversations into popular music. And not after what happened in Stockton.

Patrick Purdy was a dysfunctional drifter who’d developed a hatred for Asian immigrants and an affiliation with the Aryan Nations. While studying welding in San Diego, Purdy was heard to complain about the number of Asian students. The 24-year-old had an affinity for guns; he and his brother were arrested for shooting semi-automatic weapons in a state park. Around noon on Jan. 17, 1989, Purdy descended upon the elementary school he himself had once attended. After setting his van on fire with a Molotov cocktail, Purdy turned his AK-47 on a schoolyard full of children and opened fire—killing Rathanar Or, age 8; Ram Chun, 8; Sokim An, 6; Thuy Tran, 6; and Oeun Lim, 8.

“I remember the trauma of having students killed and wounded on a playground at a school. And a school is supposed to be a safe place for children,” Schardt said this past January, as survivors recalled that fateful day on its 30th anniversary.

At a time when most of the biggest black pop stars were making music that seemed almost preoccupied with reaching the whiter regions of the Top 40, Janet was making music that was as unapologetically R&B as a Bobby Brown album. “Black Cat” notwithstanding, Janet Jackson was firmly planted in the sounds of contemporary R&B. And it gave her an audience so many “serious” coffee-house favorites of the era wouldn’t have reached.

“I feel that most socially conscious artists—like Tracy Chapman, U2—I love their music, but I feel their audience is already socially conscious,” Janet told Rolling Stone in early 1990. “It’s like college kids, that whole thing. I feel that I could reach a different audience, let them know what’s going on and that you have to be a little bit wiser than you are and watch yourself.”

For all its topicality, Rhythm Nation isn’t exactly brimming with incendiary rhetoric. Many of the album’s biggest hits—smashes like “Miss You Much,” “Escapade,” “Alright,” “Come Back to Me,” and “Love Will Never Do Without You”—eschew commentary for bright, infectious sentiment; or in the case of the hard-rocker “Black Cat,” dejected aggression. But it’s the recurring themes of poverty, social injustice, child abuse/neglect, and racism that give the album its weight—even with so much romantic effervescence on display. Interludes make clear the album’s sociopolitical spirit, and the title track is the kind of anthem “We Are the World” aspired to be, but it avoids schmaltz with booming Sly & the Family Stone-sampling production and a delivery as aggressive as a Chuck D verse.

But “Living in a World They Didn’t Make” is the closest direct reference to the tragedy of Cleveland Elementary. With its emphatic outro of “Save the babies,” the song closes with a news snippet about the shooting:

“This just in: at least 5 people are dead, and 30 others wounded, after a gunman opened fire at a California school playground, and then killed himself. Apparently, the gunman, armed with an automatic rifle, shot the kids’ door...”

Released on September 19, 1989, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 proved Janet’s superstardom was no fluke; and it proved she had the vision to separate herself from her famous family’s legacy and reinvent herself without seeming calculating or hollow. A commercial and critical smash, it launched Janet into the ‘90s as one of the biggest artists in the world. Albums like Control—and later on, Velvet Rope—were personal affairs that exposed her ambitions and insecurities, but Rhythm Nation showed that she was just as formidable when her focus was outward.

“You know, a lot of people have said, ‘She’s not being realistic with this Rhythm Nation,’” she told Rolling Stone. “It’s like ‘Oh, she thinks the world is going to come together through her dance music,’ and that’s not the case at all. I know a song or an album can’t change the world. But there’s nothing wrong with doing what we’re doing to help spread the message.”

It’s been three decades since Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814, and the tragedy of Stockton is echoed in the horror stories that have unfolded at Columbine, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, Stoneman Douglas and more. As long as our ugly reality remains tethered to the violence of that day and so many others, that message, however utopian, is still one worth spreading.