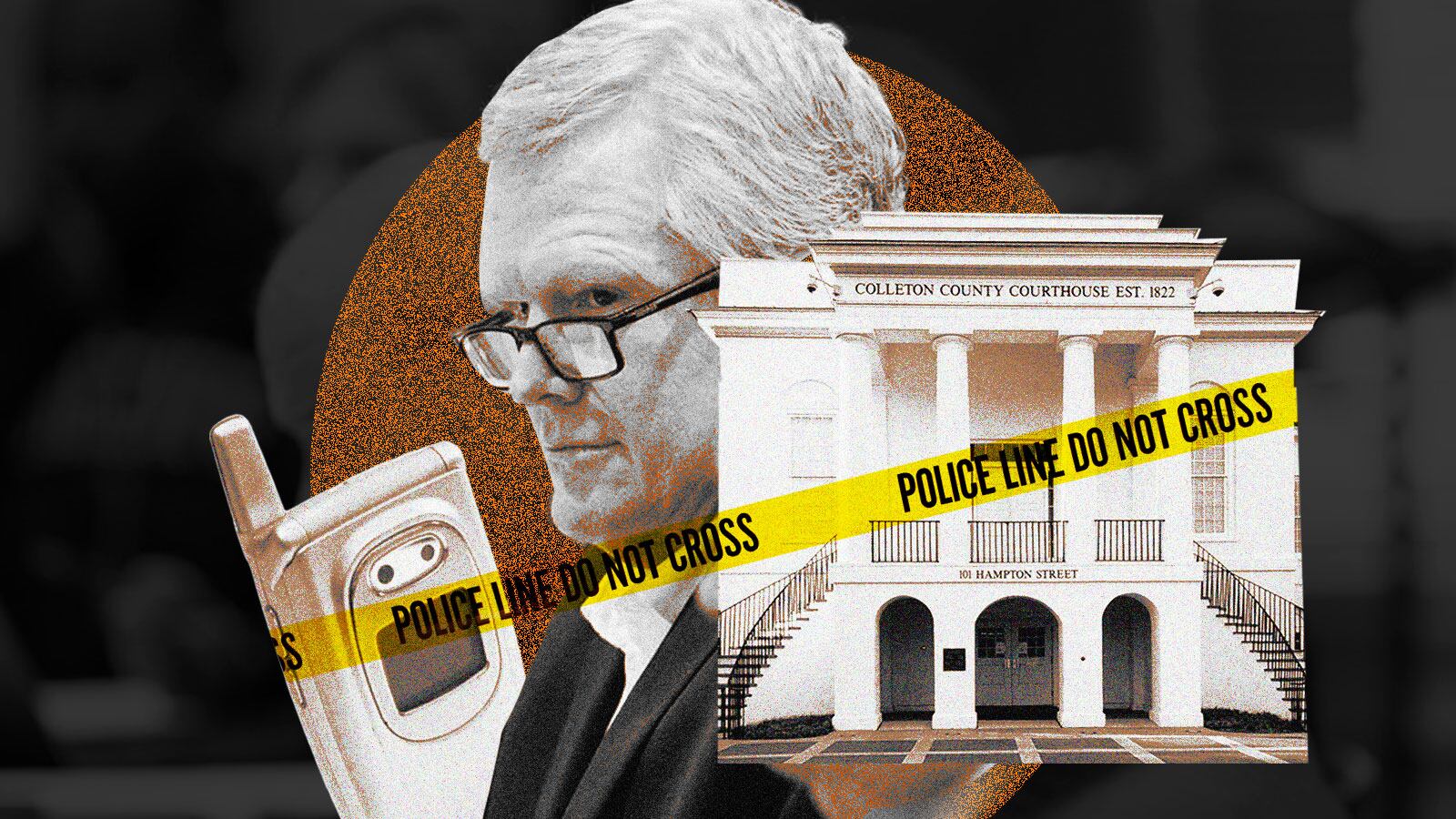

The Colleton County Clerk of Court was listening in on Alex Murdaugh’s murder trial when she noticed her security chief quickly slip into the packed courtroom.

Prosecutors had just begun to question a forensic data analyst about information extracted from Murdaugh’s Chevy Suburban in the moments after his wife and son’s June 2021 murder. But clerk Rebecca “Becky” Hill was instead intently watching her security chief as he leaned down to whisper in Judge Clifton Newman’s ear.

From her seat in the middle of the courtroom, Hill did not notice any alarming reaction from Newman, which she took as a sign that the whispered news probably had to do something with his family. Then, Newman suddenly stood up to interrupt the morning session for a sudden recess.

“Newman was so calm and laid back, and he quickly excused the jury without making a scene,” Hill said. “But then my bailiff came over to me and whispered, ‘Becky, there’s been a bomb threat.’”

As Hill sat up from her gallery seat to begin the evacuation process, which she and her team had practiced in preparation for what has been deemed “the trial of the century” in the Palmetto State, the Clerk of Court looked over at the defense table.

“Alex [Murdaugh] was smiling. Everyone saw it,” Hill said.

The bomb threat on Feb. 8, 2023, delayed day 13 of the trial for nearly three hours, forcing dozens of reporters, staffers, and members of the public to wait outside the courthouse and speculate about the cause of the evacuation. Among the group were Attorney General Alan Wilson and a University of South Carolina class that came to view the trial, where Murdaugh faced several charges in connection with the fatal shooting of his 52-year-old wife, Maggie, and his 22-year-old son, Paul, at their family estate. The threat forced authorities to temporarily block off downtown Walterboro’s main street and bring in the state bomb squad.

Ultimately, it was deemed a hoax.

It was a curious footnote in the dramatic trial, which ended with Murdaugh’s conviction and life sentence. But arrest reports obtained by The Daily Beast and eyewitnesses inside the courtroom that day provided a more detailed picture of the incident—one blamed on an inmate at a nearby detention center, Joey Dean Coleman, who allegedly called in the threat about a “bomb in the judge’s chamber.”

Spectators at the Alex Murdaugh double murder trial at the Colleton County Courthouse, after it was interrupted by a bomb threat on Feb. 8, 2023.

Joshua Boucher/The State via AP, PoolAuthorities insist that there is no direct link between the 32-year-old inmate and Murdaugh, but they have yet to provide any insight into what motivated Coleman to allegedly call in the threat from Ridgeland Correctional Institution on a burner phone. Especially since he is currently serving a decades-long prison sentence for kidnapping, assault, and battery in connection with a November 2018 convenience store robbery.

Currently, a felony arrest warrant has been filed against Coleman for making a bomb threat, but he will not be formally charged until he finishes his current prison sentence in 2045. Coleman was moved to a maximum security facility after the threat and charged by the South Carolina Department of Corrections for possession of a phone.

Neither Coleman nor his lawyers could be reached for comment. Murdaugh’s team did not respond to a request for comment.

“I believe there was no other reason for the call other than to disrupt the trial and unnerve the jury,” Eric Bland, who represents one of Murdaugh’s victims in his financial scheme and was inside the courtroom the day of the threat, told The Daily Beast. “I still think someone was doing Alex a favor.”

A redacted Colleton County Sheriff’s Office report states that the ominous call came into the courtroom from an “unavailable” number around 12:22 p.m.

Around that time, Murdaugh jurors had finished hearing damning testimony from the former lawyer’s longtime paralegal, who revealed that she was the one who first discovered her boss had been stealing from his family’s law firm for years. The testimony was crucial because it bolstered the prosecution’s argument that the discovery of his financial crimes ultimately spurred his decision to murder his son and wife.

“He’s been lying to me this whole time,” Annette Griswold told the jury. “He’s had these funds. He lied to me.”

Hill, however, said that the trial testimony wasn’t the only court drama that morning. Earlier that day, she said, Murdaugh’s sister had caused a stir in the packed courtroom after passing a book to her brother from a member of his defense team.

The jailhouse contraband was not run past the victim’s advocate, who Hill said “was waiting for a pause in testimony” to bring up the violation. (CNN reported that the book was John Grisham’s The Judge’s List. The violation was among several that Hill, who has since written a book about the landmark trial, said resulted in the court’s decision to move Murdaugh’s family further back in the courtroom.)

Unbeknownst to the victim’s advocate, however, trouble was looming in the general sessions department on the bottom level of the courthouse. Hill said that for about an hour, an unknown number had been calling the building, but staffers did not answer, in line with employee policy about unidentified calls.

“The guy called for an hour at one extension. This guy kept calling, calling, calling, and they just let it call,” Hill said. But then Coleman allegedly tried another extension, landing his call in front of General Sessions Court Specialist Amy Shaw, who Hill said answered the phone. (Shaw declined to comment to The Daily Beast.)

The arrest report states that Coleman was “talking very quietly” when he alleged there was an explosive device in the most secure area of the courthouse, already on high alert because of the Murdaugh trial. The report states Coleman repeated the threat twice before the clerk hung up the phone and informed security.

“Everyone moved pretty quickly after that,” Hill said, explaining that after she was informed of the threat, she and the bailiff quickly moved to open the courthouse front doors for two exit points. “The good thing is that we had already planned for this before the trial. So we knew exactly what to do, and it went exactly according to plan.”

From Bland’s vantage point three rows behind the prosecution table, the courtroom that was listening to South Carolina Law Enforcement Division (SLED) forensic data analyst Brian Hudak immediately knew something was wrong because Newman called for a break “during an abnormal time.”

“But he was extremely calm and didn’t look like he wanted to alarm anyone,” Bland said.

Bland added that he saw defense lawyer Jim Griffin whisper to his client about the alleged threat—and that he, too, saw Murdaugh grinning in response—before he and his fellow court viewers were quickly escorted out of the room and onto the front lawn of the government building. Aimee Zmroczek, a criminal defense attorney representing Murdaugh’s co-defendant Curtis Eddie Smith, was also in the courtroom that day and explained that everyone outside the building was trying to figure out what was going on.

“It was hush-hush at first,” she told The Daily Beast. “But then, of course, word started to get out. It was surprising to me how laid back everyone was. Usually, when there is a bomb threat at a school, they bring dogs and move people further away from the building. That didn’t happen here.”

Eventually, after SLED authorities confirmed there were no threats or devices located inside the courthouse, Newman brought back the jury and resumed the trial as if nothing had happened.

Alex Murdaugh is escorted back into the courtroom for his double murder trial at the Colleton County Courthouse on Feb. 8, 2023.

Andrew J. Whitaker/The Post And Courier via AP, PoolThe arrest report, however, provides details on how authorities were quickly moving to figure out the validity of the threat and who was responsible. Colleton County Sheriff’s Office Detective Laura Rutland, who also testified as a witness in the Murdaugh trial, wrote in the report that analysis of the phone number that called in the threat revealed that it was “pinging at the medium security Ridgeland Correctional Institution.”

When three correction officers entered cell #57, the report states that they “observed inmate Joey Coleman with a cell phone in his hand that he quickly hid underneath his pillow.” The report states that Coleman ultimately admitted that he did own the black Motorola touch screen phone but “denied making the phone call to the courthouse.”

Further analysis of the phone, which included finding a Gmail account associated with Coleman, confirmed he owned the phone, the report states. Coleman’s arrest warrant adds that probable cause for the eventual charges against him includes “physical evidence, technical evidence, gathered intelligence, and statements from individuals received during the course of the investigation,” but details are not immediately clear.

“The threat did not seem to rattle the jury. I think a part of them enjoyed the break, and when they came right in, they went back to business,” Hill said, noting that weeks later, Murdaugh jurors reached a guilty verdict in less than three hours.

Alex Murdaugh listens to prosecutor Creighton Waters’ closing arguments in his trial for murder at the Colleton County Courthouse on March 1, 2023.

Joshua Boucher/The State/Tribune News Service via Getty ImagesStill, authorities have not shared information about why Coleman would allegedly commit a federal crime from behind bars.

The South Carolina native had an extensive criminal history stretching back over a decade, including a 2010 conviction for third-degree burglary, a 2011 conviction for second-degree burglary, and a 2018 conviction for possession with intent to distribute cocaine. In 2020, Coleman was sentenced to 30 years in prison after pistol-whipping a store clerk and firing multiple shots before stealing “fistfuls of cash,” prosecutors said.

After his latest conviction, Coleman moved around several state facilities before eventually landing at Ridgeland Correctional Institution on Jan. 24, 2023—days before the rigorous jury selection began in Murdaugh’s trial.

During his time bouncing around facilities, Coleman faced two disciplinary sanctions on Sept. 25, 2020. Inmate records state that Coleman was found in possession of a weapon and affiliated himself with a prison gang. He was punished for both infractions with a loss of canteen privileges for 145 days, 10 days of disciplinary detention, a loss of visitation privileges for 45 days, and a loss of phone use for 100 days, inmate records show.

According to FitsNews, citing records obtained through public information requests, the transfer to Ridgeland came at Coleman’s request because he was facing hardship at McCormick Correctional Institution, where he had been placed for two years.

Around that time, Coleman also began sending hand-written letters from jail. In a January letter, penned the day before his transfer and viewed by The Daily Beast, Coleman wrote to the Hampton County Clerk of Court and requested a copy of a post-conviction relief form. He also asked that the judge who sentenced him in 2020 be informed that he is “schizophrenic” and desires “an evaluation.”

“Ask [the judge] could i [sic] have a resentencing hearing please? Ground temporary insanity,” Coleman wrote. “Hard to be remorseful about something that you dont [sic] remember doing. Just saying.”

Days later, on Jan. 28, Coleman’s mother paid him a visit, according to FitsNews. Inmate records indicate that the day before he allegedly called in the fake threat, Coleman earned work credit as a wardkeeper.

After his transfer to Broad River Secure Facility, Coleman seemingly took steps to make the best of his situation. On Feb. 27, inmate records state he completed the Employability Skills Curriculum—the first time Coleman completed a training course while incarcerated. By April, Coleman had been transferred out of lockup, and a South Carolina Department of Corrections spokesperson confirmed that he is currently in a “general population dorm” at the facility.

But as for Coleman’s motivation—fame, a favor, or something else entirely—those who fled from the bomb threat are still in the dark.

“There is so much more to this story that we don’t know. And I don’t know that we will ever know,” Zmroczek said. “It’s extremely frustrating.”