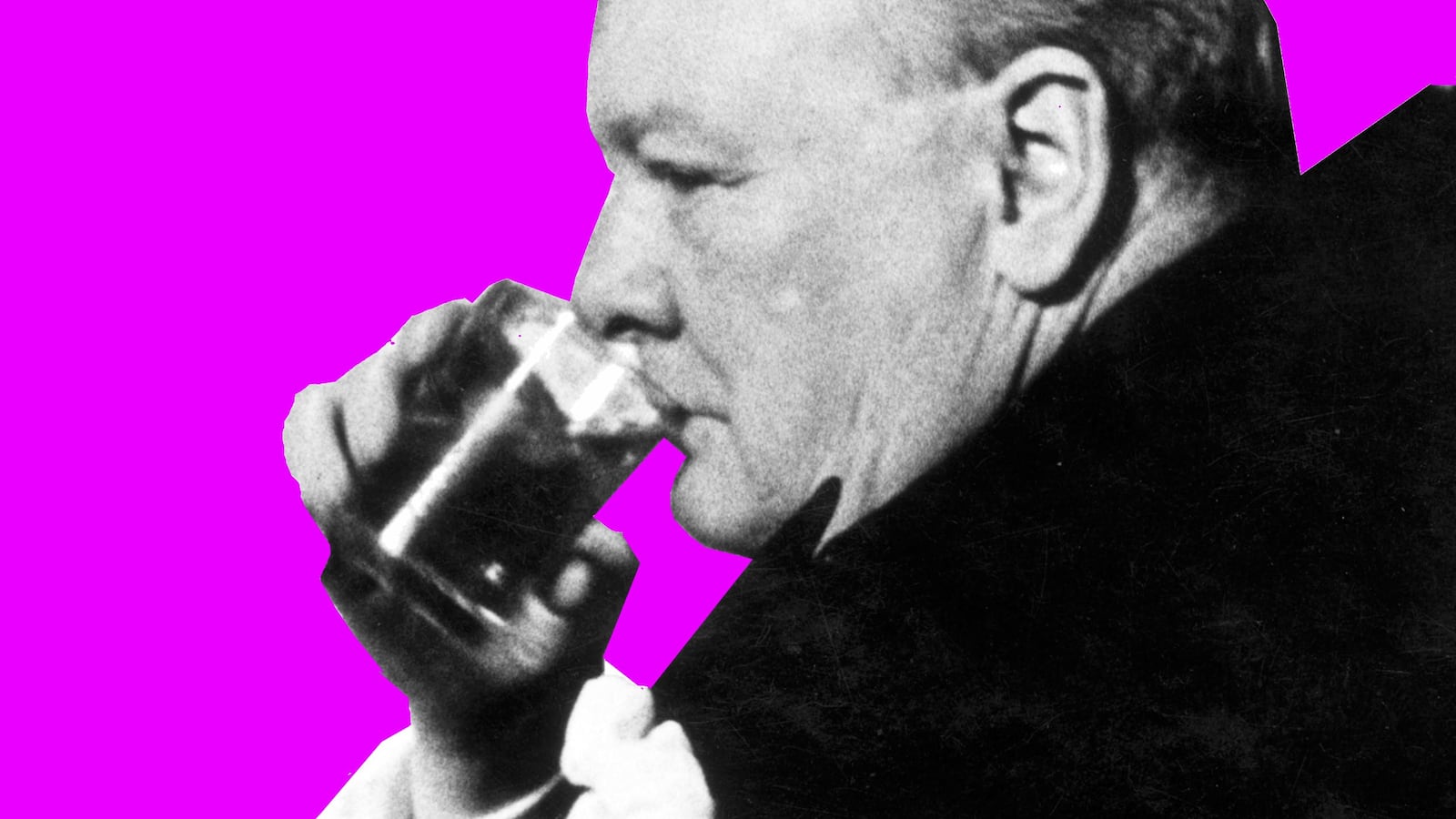

“How do you manage drinking during the day?” asks a wary King George VI as he watches Winston Churchill consume a bottle of white wine at lunch in Darkest Hour.

“Practice” replies Churchill.

Before this scene we have seen Churchill never straying far from a large glass of whisky and, indeed, the movie begins with a shot of his breakfast tray – the full English breakfast of fried eggs, sausage and bacon – along with a whisky.

Later, we hear some of Churchill’s contemporaries calling him a drunk, a view also propagated by Adolf Hitler. Of course, no drunk could have so coherently directed a war nor so fluently deployed a language. Churchill enjoyed drinking and his protean gifts thrived on it.

But the king’s question is no doubt on the minds of many Americans as they see Gary Oldman’s extraordinary performance as Churchill. With some exceptions (I’m thinking Roger Sterling and pals in Mad Men), America has never really embraced drinking during the day as Europeans have. The image of Ray Milland desperately heading for the first neighborhood bar to open in Lost Weekend remains a stigmatizing symbol of dipsomania.

Too bad. Few people can actually manage drinking as Churchill did, but a large part of the art of drinking is to recognize the wonderful conjunction of particular hours throughout the day and a particular libation…and, quite often, a particular place.

To be sure, this can be very subjective and in my case it has involved a lot of time (and, as Churchill said, practice) spent traveling in Europe.

I can’t think of a more satisfying example than a morning pit stop at the La Boqueria market in Barcelona. All the ripeness of the Catalonian cuisine is on concentrated display beneath the art deco iron roof of this wondrous place on the city’s great boulevard, the Rambla. In the morning, as the city’s energy begins to pick up, the locals shopping for the day’s kitchen needs often stop at a small bar in the market for a copa, a slender glass of chilled sherry, and a small plate of jamon – ham sliced so thinly that it’s almost transparent.

Sherry is no longer a mainstream drink for Americans. As a result it is probably one of the best values of any wine, when you consider that the best sherries involve as much patient cellaring and crafting as an expensive Champagne.

Avoid the few mass-produced brands like Harveys, which is known for the abomination called “cream” sherry that is fit only for consumption at an event like a bad office party.

In Barcelona the morning sherry is almost invariably a fino, the driest, and of the finos the most elegant are the manzanillas. (Always chilled, and never with ice.) And, as is often the case with wine, there is a bit of accidental magic in the way the best manzanillas are produced. In my opinion, they don’t come from Jerez, the city that dominates the sherry industry, but from the small port city of Sanlucar de Barrameda, at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River near Cadiz, where the Atlantic meets the Mediterranean.

The theory is that the salty marine climate adds a distinctive quality to the wine as it ages in casks that are only loosely stoppered with a layer of air left above the wine. Left exposed in this way, the wine develops a surface crust called flor, or flower, and the yeasts in this crust control the development and flavor of the sherry as it matures over several years.

Even if the science sounds a bit shaky I’m a great believer in this kind of alchemy because you can actually taste the difference in the sherry – some producers in Jerez send their sherry to Sanlucar to acquire the same class, but they never quite equal the locally produced wine. Two good manzanilla producers whose bottles you can find fairly easily are La Gitana and Lustau – half liter bottles are between $15 and $20. Also look for the hand-bottled Bodegas Yuste La Kika, 10 years old, around $30 for a half.

I will push the importance of quirkish local geography to the sherry experience even further. It’s best if the ham paired with the manzanilla is jamon iberico de bellota. This is meat cured from Iberian blackfoot pigs bred in southwestern Spain that in the final months of their lives gorge exclusively on fallen acorns.

In Barcelona La Boqueria may present a visitor with the biggest rush of sensory stimulants for the ritual – the mingled scents of fruits, meats, fish, cheeses, spices – but elsewhere on the Rambla and in scores of other places throughout Spain there are small bars and bodegas where you can sip the copa and sample many variants of the jamon well before noon. (The sherry combines equally well with grilled octopus or shrimp.)

Of course, as the Rambla demonstrates, you can’t really have ingrained rituals like these unless you have the street culture to support them. In France the backbone of that culture has always been the brasserie. Every French town, no matter how small, once had a brasserie as an 18-hour comfort zone. That’s not so true now, with the influx of fast food franchises, but the brasserie hangs on in many cities.

I have a particular loyalty to one drink that I was introduced to decades ago in a brasserie on the Avenue Wagram in Paris. It was one of those mornings after a long night before. A good brasserie waiter recognizes the condition, and on this occasion he recommended scrambled eggs, black coffee – and a shot of marc de Bourgogne.

I had never heard of the stuff. It came neat, in a small shot glass. I never caught sight of the actual bottle. I was awake enough to recognize a brandy-like smokiness in the glass, but it didn’t have the fumes of a brandy. As addled as I was, I knew that this was a memorable moment when the chemistry of the eggs, the coffee, the charge of the drink and the place seemed perfect.

This tipple led me on a search to a little-known byway of French viniculture. “Marc” translates as “residue.” You could say it’s the dregs left after the grapes have given up all their juice to the wine: a pulp, or cake, composed of grape skins and pips. The final drink is distilled like whisky is from a mash – but of course whisky comes from grain and this comes from the grape, no matter how far removed from the original grape. Another name for it is pomace brandy even though brandy begins not as a cake of residue but as specially selected grapes. This is the kind of confusion that French winemaking, with its archaic layers of regulations and definitions, throws in the path of anyone trying to understand how a wine is produced.

Other regions of France produce marc – the biggest marc distillery is in Champagne, where the marc is unctuously sweet, but marc reaches its deepest flavors in Burgundy - and its steepest price.

The most coveted vineyard in the world is the 4.46 acres of Romanee-Conti where by an act of divine chance and centuries of careful grape selection the most illustrious of all red burgundies is made, producing no more than 6,000 bottles a year. A bottle of the 2005 vintage Romanee-Conti will cost you around $20,000 – if you can actually find one, since it is rigorously rationed. A bottle of marc from Romanee-Conti is a relative snip at a mere $1,000.

To describe this wine one merchant in London offers the following incontinent cascade of winespeak: “Mellow and aromatic nose reveals notes of toffee, spice, acacia, nutmeg and apricot, hugely complex with an indulgent medley of savory notes and a long intense finish. Best enjoyed as a decadent way to end a special meal.”

This is nuts. When it gets down to basic pulp the greatness or otherwise of a wine has already been extracted in the pressed juices. How the marc is then distilled and, particularly, how it is then nurtured and aged over years in the barrel is important and there are significant differences in quality (cheap marc is little better than firewater) but nothing that justifies paying a thousand bucks – you are paying about $900 just for the label.

For example, a bottle of vintage marc from several producers within the appellation of the Hospices de Beaune can be had for between $80 and $100 and delivers the essence of what this drink should be, never as refined or enduring as a fine Cognac but a wine that has a very different role from a Cognac. Many people do, indeed, enjoy it to close a meal, but for me a marc de Bourgogne will always be at its singular best at around 11 in the morning, as a jolt to the brain and appetite and ideally with black coffee and scrambled eggs.

And now we must return to the all-engulfing appetites of Winston Churchill: “My tastes are simple. I am easily satisfied by the best.”

Churchill came from a generation and a class for whom Champagne was regarded as an everyday drink – at any time of the day. He kept up this habit even though he was often close to being broke, living from check to check earned through journalism and speechmaking. Late in life, established as the Great Man, he made known that since 1908 he had been drinking the Pol Roger brand and they responded with a regular supply of cases as a gift. After his death they introduced a special bottling in his honor, Cuvee Sir Winston Churchill, and it continues to be a very profitable exploitation of his name.

I’ve never found Champagne an easy drink to like. It’s important to remember that it was originally created to make wine from grapes – principally pinot noir and chardonnay – that were tricky to vinify as high quality still wines in such a northern location. A technique was developed to give them bubbles through fermentation that, at two stages, adds sugar to counter the natural acidity of the wine.

The truth is that a lot of mass-produced Champagne trades on the idea that it is a luxury wine when, in fact, they are just overpriced mediocre wines. A handful of long-established houses (and a number of artisanal small producers) rise well above that level and a few produce a drink that is really worth the money – my own favorites for both vintage and non-vintage champagnes are Krug and Louis Roederer.

There is, however, a way to make cheap Champagne palatable as a first drink of the day. Once more I discovered how this works by pure dumb luck.

I was in Dublin. It was late April and the weather was miraculously summer-like. Dublin is a city that provides many occasions for serious drinking and this happened to coincide with one of the most glamorous, the annual Trinity Ball. Graduates of Trinity College celebrate the end of the academic year in a style that has been called Europe’s largest open air all-night private party.

As the party wound down around dawn small groups of revelers left the college campus and drifted down to the banks of the River Liffey, the men in tuxedos and the women in gowns that many of them had made themselves. The black ties were loosened. The dancing shoes were kicked off. In the sultry air it felt more like Rome, with the river doubling for the Trevi Fountain.

My wife and I had gone down to the river from our hotel, on our morning walk. We were drawn to this happy assembly and, in due course, found ourselves moving with them to a pub. The drink of choice was black velvet – draught Guinness mixed with Champagne. As with my first glass of marc, I never got to see the Champagne label. The wine had been subsumed into the creamy foam surface of the Guinness, as though intended by nature.

If there was ever a time to initiate the civilized ritual of the first drink of the day it surely is the first day of a new year, and in the case of 2018 to flush away the horrors of 2017 and hope that better things can still seem possible.