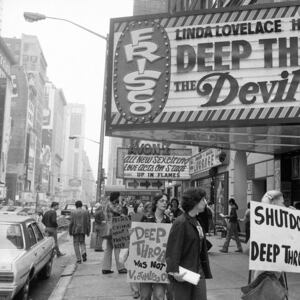

In early 1980, a 31-year-old woman named Linda Marchiano called a press conference. Just eight years earlier, Marchiano’s performance in the adult film Deep Throat under the nom-de-porn Linda Lovelace had earned her a cult celebrity status, two unsuccessful sequels, a tell-all memoir, a follow-up tell-all for what the first one hadn’t told, a string of photoshoots in men’s mags from Playboy to Esquire, and even a hat tip from the renowned Watergate whistleblower. But Marchiano hadn’t called the conference for another reprise of her role as oral ingenue. Now a housewife and born-again Christian, nursing an affection for Cool Whip, daytime soaps, and “pink pinafore[s] embroidered with the word Mommy,” Marchiano was there to promote a new book, Ordeal, and to announce what it detailed—namely, that she had been forced into pornography; that Chuck Traynor, the star’s ex-husband and one-time director, had beaten her, terrorized her, and pressured her into sex work upon threat of “disfigurement and death;” and that the movie itself, hailed as the linchpin of the Golden Age of Porn, did not depict, as many had claimed, the sexual liberation of a young woman, but her rape.

The story fell on some deaf ears. (“I expect people not to believe me,” she told The Washington Post at the time. “Catholic girl, policeman’s daughter, living in a house where the pin money came from Tupperware parties. I mean the easiest thing for people to do in society is to say, ‘I don’t believe it.’ That's the world’s greatest cop-out.”) But others were listening intently. At the conference that day, Marchiano was joined by some of the biggest names in second-wave feminism, the vanguard of the anti-pornography crusade, among them: Gloria Steinem, Catharine MacKinnon, members of the radical feminist group Women Against Pornography, and the ferocious, bleakly hilarious, overall-wearing goliath of the movement—the writer and activist Andrea Dworkin.

By the time of the conference, Dworkin was already well on her way to becoming the most hated face of the feminist sex wars—a kind of “inverted sex symbol,” as writer Ariel Levy once put it, or “perhaps the most misrepresented writer in the Western world,” as John Berger did. But in some ways, Dworkin’s reputation as a one-dimensional, anti-porn man-hater—a feminist caricature which followed her to the grave and which a new collection of her writings, Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, published by Semiotexte this month, effectively complicates—began in earnest that morning.

ADVERTISEMENT

Marchiano’s story resonated with Dworkin. In more than one respect, their trajectories were similar. The porn starlet was born in the Bronx to an absent cop father, and a cold, dictatorial mother. Dworkin came from Camden, New Jersey. Her father, as she put it, “was not a rolling stone,” but a devoted provider who worked “two jobs most of the time and three jobs some of the time.” Her mother, a chronically ill housewife who “experienced [Dworkin’s] inner life as a reproach,” often told her daughter that she “loved [her] but did not like [her].” Marchiano, née Boreman, was a Catholic girl once dubbed “Miss Holy Holy” for her high school stance on sex, had gotten knocked up at 19, forgone professional dreams after injuring her liver in a car crash, and linked up with Traynor, an amateur porn director, in part to escape from her parents’ home.

Dworkin, a Jewish girl in a white Christian suburb, grew up with her own history of violence and disillusionment, including a rape at age 9 which her parents didn’t report. At 18, she left home for a lukewarm undergraduate career at Bennington, got brutally probed by two prison doctors following her arrest at an anti-Vietnam protest in Manhattan, and fled the States to join a collection of Dutch anarchists. She married a man in Crete, who kicked, hit, and “bang[ed her] head against the floor until she passed out.” When she escaped her husband at age 25 to discover her parents would not take her back, Dworkin was homeless for a time. She shuffled between houseboats, friends’ kitchens, a hippie commune, an abandoned German mansion, and an experimental movie theater, prostituting for money, until a failed drug-smuggling deal landed her enough cash to leave. In 1972, the year Deep Throat hit theaters, Dworkin vowed to “use everything [she knew] in behalf of women’s liberation.” All that to say: when Marchiano later outed herself as a battered wife, Dworkin didn’t exactly fall in the critical camp.

Instead, two weeks after the conference, according to Susan Brownmiller’s In Our Time: A Memoir of Revolution, Dworkin, Steinem, and MacKinnon met with Marchiano about taking legal action. When they discovered the statute of limitations for Marchiano’s charges had expired, the ex-pornstar backed out of the group. But, somewhat against her wishes, Marchiano became Dworkin’s cause célèbre, the inspiration behind a piece of legislation, drafted with the help of MacKinnon, known as the “Dworkin-MacKinnon Antipornography Civil Rights Ordinance.” The bill was a watershed moment. It was the first piece of policy to consider pornography as a civil rights issue, proposing legal recourse for women who believed they had been directly harmed as a result of adult content. It was also an incredible, staggering failure.

For many, the ordinance smacked of censorship, representing the first blow in a campaign to eradicate the adult industry entirely, and—although the bill itself imposed no limits on pornography production—Dworkin didn’t do much to dispel this impression. “Pornographers use our bodies as their language,” she once said. “Anything they say, they have to use us to say. They do not have that right. They must not have that right.” She also testified at the Meese Commission, a controversial Reagan-era investigation into porn, which drew widespread criticism as unambiguous government suppression, not only from obvious opponents like Playboy and Penthouse, but from writers like John Irving and organizations like the American Booksellers Association. Though iterations of the bill passed in some cities, all of its minor victories were stamped out by higher courts within a matter of months. The only thing it seemed to accomplish was to divide the era’s feminist movement, perhaps fatally so, and secure Dworkin’s reputation as a sour killjoy, a “preacher of hate,” as one obituary writer put it, whose contempt for men and sex were matched only by her often-ridiculed indifference to personal appearance.

That vision of Dworkin loomed over her work. She was pilloried in the media—critics spread rumors about her alleged interest in incest and Hustler ran a series of explicit cartoons featuring Dworkin (in one of them, a guy who self-describes as “a quiet, sensitive, misunderstood Jewish pimp for sorecovered, starving children from Haiti,” gets into various XXX scenes, noting at one point, “While I’m teaching this little shiksa the joys of Yiddish, the Andrea Dworkin Fan Club begins some really serious suck ‘n’ squat. Ready to give up holy wafers for matzoh yet, guys?”). Dworkin pushed back —she sued Hustler for defamation and lost—but the smears stuck. In a New York Times obituary following her death in 2005, the critic’s friend and ordinance-drafting partner, Catharine MacKinnon, wrote that, “over the course of her incandescent literary and political career, she also became a symbol of views she did not hold.” It’s a legacy that Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, edited by writer Amy Scholder and Johanna Fateman, founding member of early aughts electronic group Le Tigre, attempts to rattle, by putting “the contentious positions [Dworkin’s] known for in dialogue with her literary oeuvre,” as Fateman writes in her introduction.

The cartoon Dworkin is well represented in the collection—it samples her two most famous polemics: Pornography: Men Possessing Women, published the year after Marchiano’s press conference, which considers adult entertainment as a kind of genocidal propaganda (the opening epigraph describes a snuff film by Joseph Goebbels, who shot the trial and execution of a group of German generals); and Intercourse, where Dworkin famously looked at cis-heterosexual sex as a metaphor for the female condition.

But Last Days at Hot Slit also includes works that ring truer to today’s cultural vernacular. It excerpts Dworkin’s first book, Woman Hating, a “seductively rough-hewn” and somewhat hopeful analysis which considers gender inequality not only as an ongoing crisis, but as a class and race issue, riffing on arguments which could have been mined from today’s progressive left (“There is certainly no program to deal with the realities of the class system in Amerika,” she says in the introduction). There’s also an essay from Right-Wing Women, Dworkin’s critique of women who become complicit in their own suppression, a nearly-sympathetic portrait of Reagan-era agitators, but one easily extended to the Pennsylvania soccer-moms of modern day; and her reflections on human rights violations in the West Bank, which are almost as radical now—in a moment when support for BDS or criticizing AIPAC can trigger widespread condemnation—as they were then.

Dworkin’s parallels to Marchiano went beyond mere biography. After her conference, Marchiano returned to her Catholic roots, making a 180-degree transition from pornstar to born-again proselytizer. Dworkin was also a proselytizer, though more in methodology than message. “She is, I always thought, our Old Testament prophet raging in the hills, telling the truth,” Gloria Steinem once told Democracy Now!’s Amy Goodman. Dworkin was dogmatic—it’s part of what made her so hard to like. She had an endless list of enemies, many of them her former friends. In an essay called “Goodbye to All This,” published for the first time in Last Days at Hot Slit, the critic goes for the jugular, attacking a litany of feminist peers, some whom were once on her side. “Goodbye to stupid feminist academics who romanticise prostitution and to stupid feminist magazine editors who romanticize pornography and fetishism and sadomasochism,” she writes. “Goodbye Women’s movement, hello girls.”

But the collection also captures Dworkin’s more tender moments: Mercy, her raw, fragmented, first-person debut novel; My Life as A Writer, a loving account of her childhood, the parents who would disown her, and her first story about “a wild woman, strong and beautiful, with long hair and torn clothes, on another planet, sitting on a rock”; and My Suicide, a long letter found after her death, describing her rape in a hotel room in Paris at age 52 (“Please help the women,” she concludes. “Please let me die now.”)

Dworkin was a kind of cartoon: a larger-than-life figure who loved guns, who abstained from sex, who kept a poster in her room that read “Dead Men Don’t Rape,” who trafficked in explicit language and vulgar description, and who often screamed “The First Amendment was written by slave traders!” But she wasn’t the neat caricature history has made her out to be. In one of her short stories, a piece called Listen, Dworkin wrote: “I have no patience with the untorn, anyone who hasn't weathered rough weather, fallen apart, been ripped to pieces, put herself back together, big stitches, jagged cuts, nothing nice." Last Days At Hot Slit pays homage to the Marchiano-era Dworkin, to the anachronistic anti-porn persona everyone loves to hate, but along the way, it makes some much-needed jagged cuts.