In the winter of 2018, Andrew Rannells and Tuc Watkins arrived at a New York City photoshoot for T, The New York Times Style Magazine, alongside producer Ryan Murphy and the unprecedented ensemble cast of The Boys in the Band: Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Matt Bomer, and a roster of out gay celebrities co-starring in the 50th anniversary revival of Mart Crowley’s landmark play, all playing gay men without any risk to their careers or public image.

Rannells and Watkins were cast as Larry and Hank, lovers in 1968 who had been living as “roommates,” torturing each other over warring expectations when it comes to sex, monogamy, and commitment. The actors were instructed to act vaguely in character while posing for the magazine’s photos, which meant the pair spent the morning lightly flirting.

“I remember standing next to Tuc and not knowing him super well, but looking at him and thinking, ‘Ah, fuck. This is going to happen isn’t it?’” Rannells tells The Daily Beast. “‘We’re going to be those two actors who have a showmance.’”

He was right. The two did begin dating toward the end of The Boys in the Band’s Broadway run in the summer of 2018, but it wasn’t just a tryst that expired on closing night. They’ve been in a relationship ever since, coming out publicly as a couple a little over a year ago in separate Instagram posts.

Their social media feeds and press interviews have since become public records of their life together as a family: birthdays, trips, goofy selfies. Since the pandemic started, for example, Rannells has played guest tutor during virtual learning sessions for Watkins’ seven-and-a-half-year-old twins, who he had via a surrogate in 2013. (A photo Rannells posted of one of the twins slumped over his laptop in defeat hints at how well that was going.)

Rannells’ career began on Broadway, where he starred in The Book of Mormon, Falsettos, and Hamilton, before breaking out in Hollywood with roles on Girls, The Intern, and the upcoming Netflix film version of the musical The Prom, opposite Nicole Kidman and Meryl Streep. Watkins made his name as a daytime TV heartthrob, starting his nearly 20-year run as David Vickers on One Life to Live in 1994, with memorable roles in The Mummy and Desperate Housewives that followed.

That the couple—Rannells is 42 and Watkins is 54—have been so casually and affectionately public with their relationship is still, in 2020, remarkable. But it’s perhaps even more poignant considering that the two occasions they have played lovers on screen in the time that they’ve been dating (itself an unusual accomplishment for a Hollywood gay couple) have been in period pieces where their characters were closeted, romancing in secret, and meant to feel shame.

A first round of giggly “what is it like to shoot love scenes with your real-life boyfriend” press happened earlier this year when season two of Showtime’s Black Monday premiered, which cast Watkins as a politician secretly hooking up with Rannells’ Wall Street stockbroker in 1980s New York. Now the curiosity is piqued again, with the movie version of The Boys in the Band available Wednesday on Netflix, reuniting the Tony-winning revival’s original cast and its director, Joe Mantello.

Crowley’s 1968 play dramatizes, as culture writer Mark Harris says, “the most famously toxic gay birthday party in the history of New York City.” Parsons’ character, Michael, is hosting the affair at his apartment, gathering a smattering of friends for an evening that, as booze flows and bitterness escalates, devolves into acid-soaked examinations of self-loathing and despair. It’s a crackling work of wit and insight, but also a snapshot of gay men’s caustic self-pity and internalized homophobia.

Lines like Michael’s damning proclamation, “Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse,” have memorialized the work as a lightning rod in the community. Those who condemn it as a cruel relic of shame at a certain time in history are equally passionate as those who celebrate it as “a milestone of frankness, empathy, and even liberation,” as Harris writes.

The first thing Watkins remembers about meeting Rannells in rehearsals is how warm and affectionate he was. “I remember thinking, this is going to be great, because Hank and Larry spend the entire play bickering and angry and resentful towards each other,” he tells The Daily Beast. “So to create that relationship with someone who is caring and thoughtful and lovely, we had a great experience.”

Neither can pinpoint exactly when things officially turned romantic, just that it was later in the play’s Broadway run.

“For me it was a little bit like that quote, ‘How do you fall in love? The same way you fall asleep: slowly and then all at once.’” Watkins says. “I woke up one day and realized, I think I really like this guy.”

The pair is speaking over Zoom from separate coasts. Watkins is in California, where he is “up to my eyeballs with homeschool.” The twins are in second grade, so “it’s as if I’m in second grade also.”

He clarifies that he is not the twins’ teacher, per se, but that his official title is “learning coach.” “It’s sort of a sexy title,” Rannells quips as, in another corner of the Zoom window, Watkins blushes. “I’m glad Andrew thinks it’s a sexy title.”

Rannells has been back in New York, where he just finished directing an episode of Amazon’s Modern Love anthology series, which he also adapted from a 2017 essay he wrote for The New York Times column that inspired the show.

Titled “During a Night of Casual Sex, Urgent Messages Go Unanswered,” the essay recounts when Rannells when 22 and had an apathetic night of sex with “a faceless memory from your early 20s,” a boy named Brad. He had been ignoring calls from his siblings all evening. When he finally left Brad naked in the bed to go to check his messages, he learned his father had collapsed at his niece’s birthday party, having suffered either a heart attack or stroke.

The column became a cornerstone for a book of essays Rannells published last year titled Too Much Is Not Enough: A Memoir of Fumbling Toward Adulthood, about his experience moving to New York from Omaha and floundering as he tried to find his place in the theater community and come to terms with his own sexuality.

“I kept getting these kids at stage doors on Broadway thinking that basically I was like hatched out of an egg into the Book of Mormon,” he says about why he wrote the book. “That I just appeared and all of a sudden had this great show that was a hit. But that's not the case. There were a lot of times that things were kind of rough.”

That candor, when it comes to everything from the industry to his sex life, is something that Watkins specifically admires. “I’ve always thought that if being gay was a big box store, we would put Andrew Rannells up front, as the greeter. Like, ‘This is what it’s like! It’s okay. Come on in!’”

Now that there’s public interest in his love life, it’s been interesting for Rannells to reflect on the fact that he never felt pressured to be in the closet, or worried what coming out could mean for his career. He was 32 when he starred in The Book of Mormon and was cast on Girls as Lena Dunham’s gay best friend, Elijah. After one season of Girls, Ryan Murphy cast him in The New Normal, a NBC sitcom about a gay couple adopting their first child.

“Around that time I was asked to be on the cover of Out magazine, and my publicist at the time said, ‘It’s a bell you can’t unring,’” he remembers. Even recounting the story now, he looks baffled. “I was like, ‘Well let’s fuckin’ ring it. This seems like the time.’ I was like 33 and I’d always been out. And I was also playing two gay characters on television. But I will always remember her saying that. ‘It’s a bell you can’t unring.’”

Watkins’ own experience was different, in that he actually had a public coming out, a decision that he wrestled with for decades before doing it.

It was in 2013, a few months after his twins, Catchen and Curtis, were born. The previous spring, he had wrapped his run on Desperate Housewives, on which he played one half of a gay couple that moves to Wisteria Lane. He went on Marie Osmond’s Hallmark Channel talk show Marie and revealed for the first time that he was a gay single dad and had welcomed his children via surrogate.

“I come from 20 years of working in an industry that felt like I wasn’t safe saying who I was, telling the truth about who I was authentically,” he says, remembering the time. “But something toggled over after I had kids. I thought it doesn’t make sense to not tell the truth about who I am with kids next to me. I didn’t want them to look up and see that they had a dad who was afraid to tell the truth.”

Rannells, who has seen the clip, laughs. “Who else has a public coming out story where they can say, ‘Well I told Marie Osmond…’”

“She did ask if this was the first time I’d spoken about it publicly,” Watkins remembers, “and I said, ‘Well you’re the first Osmond I’ve told.’”

Still, neither of these experiences prepared the actors for the tidal wave of attention they would receive when they “came out,” so to speak, as a couple on Instagram.

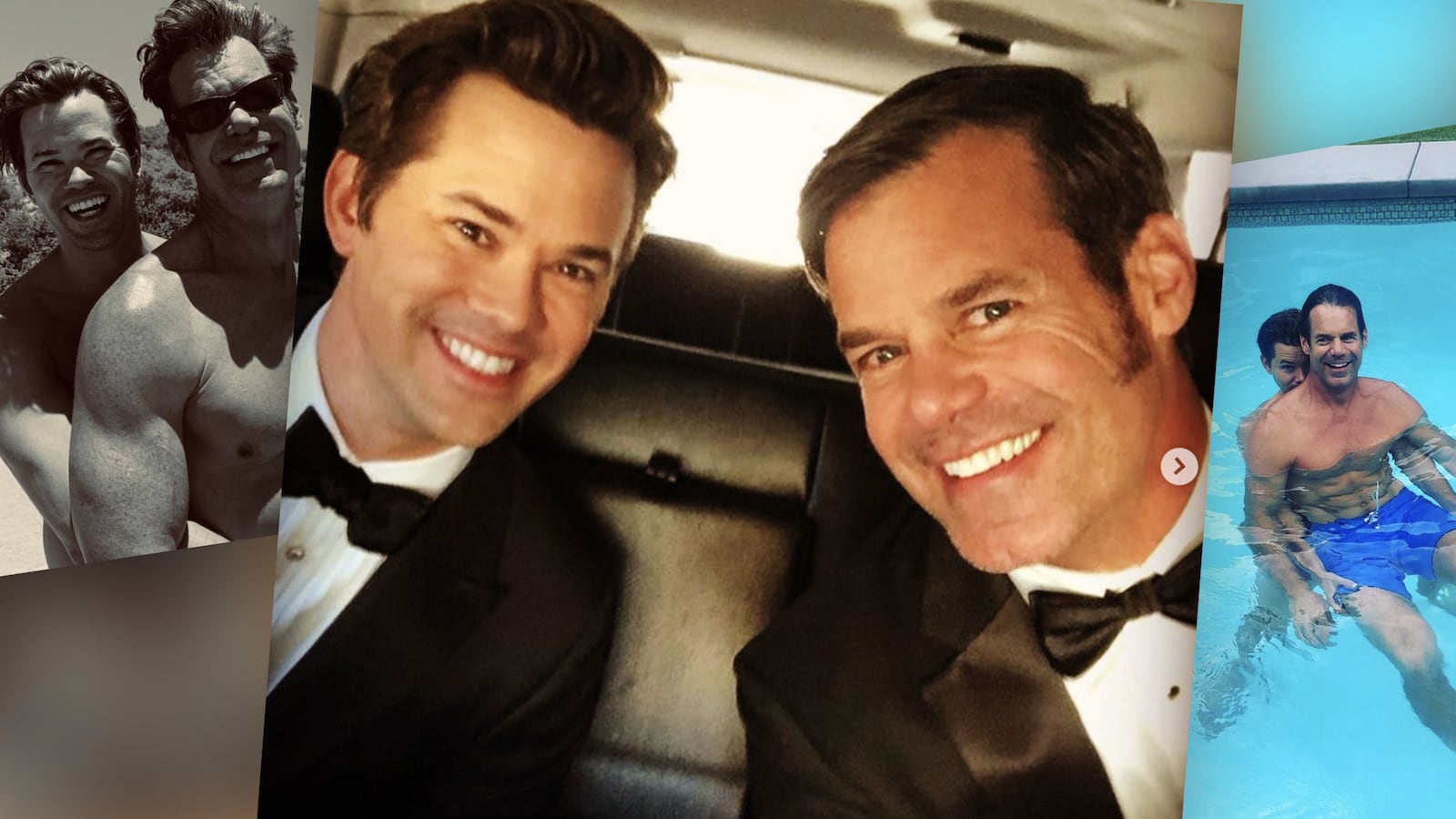

In September of last year, Rannells posted a photo of himself bashfully spooning Watkins in a pool, planting a light kiss on the back of Watkin’s shoulder. Two days later, Watkins posted his own photo of the two of them, a black-and-white picture of the pair shirtless outside, with Rannells' hands around his waist. The caption: “It’s hard to hide @andrewrannells. He’s 6’2” and shines brightly.”

“I just couldn’t not talk about it anymore,” Watkins says. “It was just out of excitement. It was just joy. You’re always a little trepidatious to put things that are intimate about your life out there for the world to see, but I just couldn't help it anymore just because I liked him so darn much.”

That “the kids were weighing in on Instagram,” as Rannells says, was certainly new for the two of them. “But there we are.”

The occasion of The Boys in the Band film coming out means the opportunity to walk down memory lane of their courtship.

The structure of the play is such that, after about 90 minutes of scorched-earth baring of their souls and insecurities about love and their relationship, their characters retreat to a balcony bedroom that’s semi-hidden behind a frosted-glass wall, where they would mime heavy conversation and cuddling, and, finally, as the lights go down on the play, tear off each other’s shirts and start aggressively making out.

“Yep, the first time we kissed was because of our job,” Rannells says. “I mean I can only speak for myself but I certainly wanted to, and I was looking forward to it. But it was strange that we were getting paid to do it.”

Watkins estimates that those 20 minutes each night is when they really got to know each other. “We were in an intimate setting, and in an intimate setting, you tend to have intimate conversations.” At least, as Rannells interjects, when they weren’t taking turns napping.

One night late into the run, one of Watkins’ good friends came in from out of town to see the play. They met for a drink after the show and the first thing his friend said was, “You’re seeing Rannells, aren’t you?” Watkins was shocked. He was, but he hadn’t told anyone. How could he have known? “And he said, ‘Well, at curtain call you guys hold each other's hand longer than you need.’”

It’s a rare experience to star in a film version of a play you spent months working on, and to do it with the same actors from that production. At this point, the cast knows each other on a deeper level, something that comes through in the performances. It’s also gratifying for them that, after doing a play that lived, breathed, and evolved, the film version is finite.

“I actually remember the last time Andrew walked out of my dressing room on our last night of the play and my heart was in my throat and my stomach was on the floor,” Watkins says. “It felt really sad. I felt like I was losing something. But something happened when we finished the movie. Somehow, it felt like it was complete. I didn’t feel the sadness.”

If one of the ending notes of The Boys in the Band is hope for the future telegraphed through the love and passion you see as Larry and Hank start to reconnect and hook up, then there’s something poignant—and certainly meta—in the fact that the actors in that scene have a happily ever after of their own together, too.

When the conversation is over and it’s time for goodbyes, Rannells and Watkins ease a little bit in their respective Zoom windows.

“Tuc, your beard is looking very handsome,” Rannells compliments.

“Thank you, I grew it this morning,” he jokes, puffing his cheeks out as if he is extruding hairs by force. “Pushed it right out.” Rannells doubles over laughing as Watkins shouts, “Miss you, Rannells!”

“Miss you, too,” he says back. “I’ll call you later.”