As soon as Boeing’s top management understood what they were looking at they didn’t like it.

Another company had produced a paragon of an airplane and they had nothing to match it. And so Boeing decided it had to do as much harm to that airplane’s chances as it could—most of all, to stop any American airline from buying it.

The company was Bombardier, based in Canada. The airplane was the Bombardier C Series, a single-aisle jet that, in several versions, could seat between 100 and 150 passengers.

ADVERTISEMENT

What was striking about the C Series was that the Canadians had combined the most advanced technologies available into an airplane that was, as a result, a generation ahead of any similar size model.

Airlines would love it because its engines were so efficient that it was cheaper to operate than any rival. On domestic routes it could make as many as 11 flights in a day, with a turnaround time at gates of 35 minutes. Passengers would love it because the cabin was quiet, the seats not cramped, the air quality noticeably better, and baggage space generous.

But creating the C Series had pushed Bombardier to the edge financially, costing around $5.5 billion to bring it to a first flight in March 2015. Like most technologically ambitious programs, this one had busted its budget and was not meeting its delivery deadlines. And its engines, made by America’s Pratt & Whitney, were equally venturesome and late because of glitches.

Nonetheless, when airlines checked it out they were impressed. So was Boeing’s chief rival, Airbus. At the 2015 Paris Air Show, Airbus’s chief salesman, John Leahy, not known for being kind to competitors, took a look at it and conceded that the C Series was “a nice little airplane.”

Delta Air Lines agreed. In April 2016, it was the first American airline to order it, for domestic routes, 75 of the first and smallest version, with options on later and larger versions.

Boeing went ballistic. It accused Bombardier of “dumping” the jets to Delta by selling each airplane at $14 million below production costs.

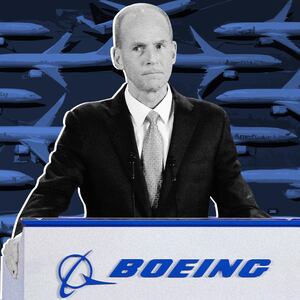

Boeing’s formidable Washington lobbying machine swung into action. Dennis Muilenburg, the Boeing CEO, had already cozied up to President Trump by agreeing to cut the costs of the future Air Force One jets. In September 2017, the Commerce Department announced a killing blow to Bombardier, imposing a 300 percent duty on every C Series sold in the U.S.

Given Bombardier’s parlous financial position, this might have been enough to wipe out the company. But Bombardier was being secretly courted by Comac, a Chinese airplane builder that had been struggling for years to produce its own single-aisle jet. To them, Bombardier offered an opening to advanced technology and a base from which to build a sales network in the West.

But on Oct. 16, 2017, to the amazement of the whole aerospace industry, Airbus announced it was taking a 51 percent stake—not in Bombardier itself but in the C Series program. Without any down payment.

In one stroke, Airbus had changed the future of the airline industry. And out-gamed Boeing.

Between them, the Airbus and Boeing duopoly covered every size of airplane except in this category, with between 20 and 30 fewer seats than standard single-aisle jets like the Airbus A320 and the Boeing 737. Until now that had been left to Bombardier and the Brazilian company Embraer. But the C Series changed that equation: It introduced the comforts and efficiency of the bigger jets to the smaller.

The president of Airbus, Fabrice Bregier, boasted that now Airbus could offer airplanes seating from 100 to 600 passengers, all with the same sophistication (a boast that should be challenged because the highest number is provided by the A380 superjumbo that is now virtually a dead duck).

The C Series brought another advantage. Unlike Boeing’s 737, its cockpit had state of the art fly-by-wire flight controls that made it compatible with the rest of the Airbus jets, giving it an appeal to the many airlines already flying them.

To ram home just how much Airbus was now able to out-game Boeing, it said it would build a final assembly line for the C Series in Alabama for those sold to American airlines, thereby removing the vulnerability to tariffs. (Many components of the jet were, in any case, made in America, in addition to the engines.)

Airbus rebranded the jet as the A220 and in February this year Delta began flying the first of a planned fleet of A220s on U.S. routes. Jet Blue has followed by ordering 60 A220s that, it says, are 40 percent more efficient to operate than the Embraers they replace. There are now more than 500 A220s on order.

The founder of Jet Blue, David Neeleman, who left the airline in 2007, is so enamored of the A220 that he is planning a new airline based on it. As with Jet Blue, this airline could be a disruptor: Neeleman is talking to Airbus about a long-range version that would open up entirely new routes between the U.S. and Europe and the U.S. and South America to serve smaller cities that don’t generate enough traffic for big jets but could be efficiently served only by the A220.

There was one consolation for Boeing and for American aerospace companies in general: China was effectively blocked from gaining an important foothold in North America and a ton of intellectual property.

But the story of Boeing’s failed attempt to sabotage a rival has a larger message.

The mindset that plotted that response to the C Series is the same one that produced by far the most damaging crisis in the company’s history, the grounding of the 737-MAX after two crashes that killed 346 people, combined.

It was well within Boeing’s skills to have produced a jet equal to the C Series. In fact, Boeing had pioneered every innovation used by the Canadians in its 787 Dreamliner: an airframe made of composites instead of metal, a vastly improved cabin climate and amenities, a significant leap in fuel efficiency.

But by concentrating all these advances in one leap, Boeing lost control of the program. The 787 was three years late and way over budget by the time it flew and was then grounded because of fires in its novel main power system that relied on lithium-ion batteries.

Even though the Dreamliner finally came right and lived up to its name—passengers love it for the quiet and airy cabin—the company lost billions in its development, and its taste for innovation.

In 2014, the then CEO Jim McNerney said, “Every 25 years a big moonshot… then produce a 707 or a 787—that’s the wrong way to pursue this business. The more-for-less world won’t let you pursue moonshots.”

Three years earlier McNerney had already acted on that belief. Instead of embarking on an all-new 737, he ordered yet another iteration of a design that had its origins in the 1960s, the MAX. McNerney’s rule was: Re-use old technology and cut costs. As a result, the MAX was an unhappy coupling of a new engine and an airplane that was—to be kind—suboptimal.

In effect, by losing its nerve, Boeing was also in the process of losing its global primacy—a dominance that had been hard won in the first place, not by trying to lock out competitors, but by learning from them and then making one leap ahead.

This happened twice as Boeing came late to the jet age, and it involved one rival company, British-based De Havilland. Britain pioneered military jets in World War II and in the early 1950s De Havilland went on to produce the world’s first jet airliner, the Comet.

De Havilland was basically a small family business and under-capitalized. Each jet was more or less hand-built. A series of early crashes, caused by a structural weakness, hampered the Comet’s acceptance, even though a later version was a success.

Boeing realized that jets, which doubled the speed of air travel, were the future—but the Comet was too small to be efficient for the kind of long-haul routes that were ideal for jets, and that a larger new jet built in Boeing’s far more efficient plants would be a gamble worth taking.

The result was the world’s first really successful long-haul jet, the 707, that first flew in 1957. It set the form for every new jet built by Boeing—and by everyone else.

The same thing happened when De Havilland developed a smaller jet for short-haul routes in Europe, the Trident. Once more it was too small and too inefficiently manufactured. Boeing took its novel design, with three engines mounted at the rear, and turned it into the 727, launched in 1962, that became one of the most common jets in the world.

In those days, nobody at Boeing thought of these gambles as “moonshots.” They were risks that had to be taken to gain ascendancy and they culminated in 1970 with the 747 jumbo, an airplane that nearly bankrupted the company but ended up as a legend.

Recalling these milestones in aviation history is not a wistful salute to an age of past glories. It’s an indictment of a culture broken by misplaced priorities. As Boeing fell back on risk-averse designs and cost-cutting, it simultaneously adopted a self-enriching policy of stock buybacks and a new focus on quarterly earnings.

And it’s not as though the bean-counting regime has proved effective. As well as the 737-MAX grounding, that has so far cost Boeing around $8 billion, two other programs are dogged by problems.

In 2011 Boeing won a contract to replace the Air Force’s aging fleet of in-flight refueling tankers with the KC-46, a conversion of the 767 airliner. Originally this contract was awarded to a consortium of Northrop Grumman and Airbus, but a blitz of lobbying by Boeing reversed that choice.

The KC-46 has been so crippled by problems that the Air Force says it will be three or four more years before it can perform its mission. It is withholding $28 million from every tanker it receives until the problems are fixed. This September the airplanes so far delivered were rendered useless because their other role, carrying cargo and passengers, was suspended because of an unsafe cargo locking mechanism.

In the meantime, the Airbus tanker that was rejected by the Pentagon is now fully operational with air forces in Europe, the Middle East, and Australia.

Then there is the 777X, an update of Boeing’s highly successful big twin-jet. Airlines have ordered 500 of these, but the first flight has been delayed by at least a year, partly because of problems with its General Electric engines, but also with the airplane: It recently failed a certification test when a cargo door blew out.

Boeing provides no end of a lesson in how a great company can lose its moxie because of an indecent lust for short-term gain. It used to be the classic American can-do company. Now it can’t do anything right.