The year is 2015 and our bodies are very, very different. The loss of a limb no longer means living in a world of restricted movement: We are now in an age of highly developed exoskeletons, glow-in-the-dark prosthetic appendages, and motorized members.

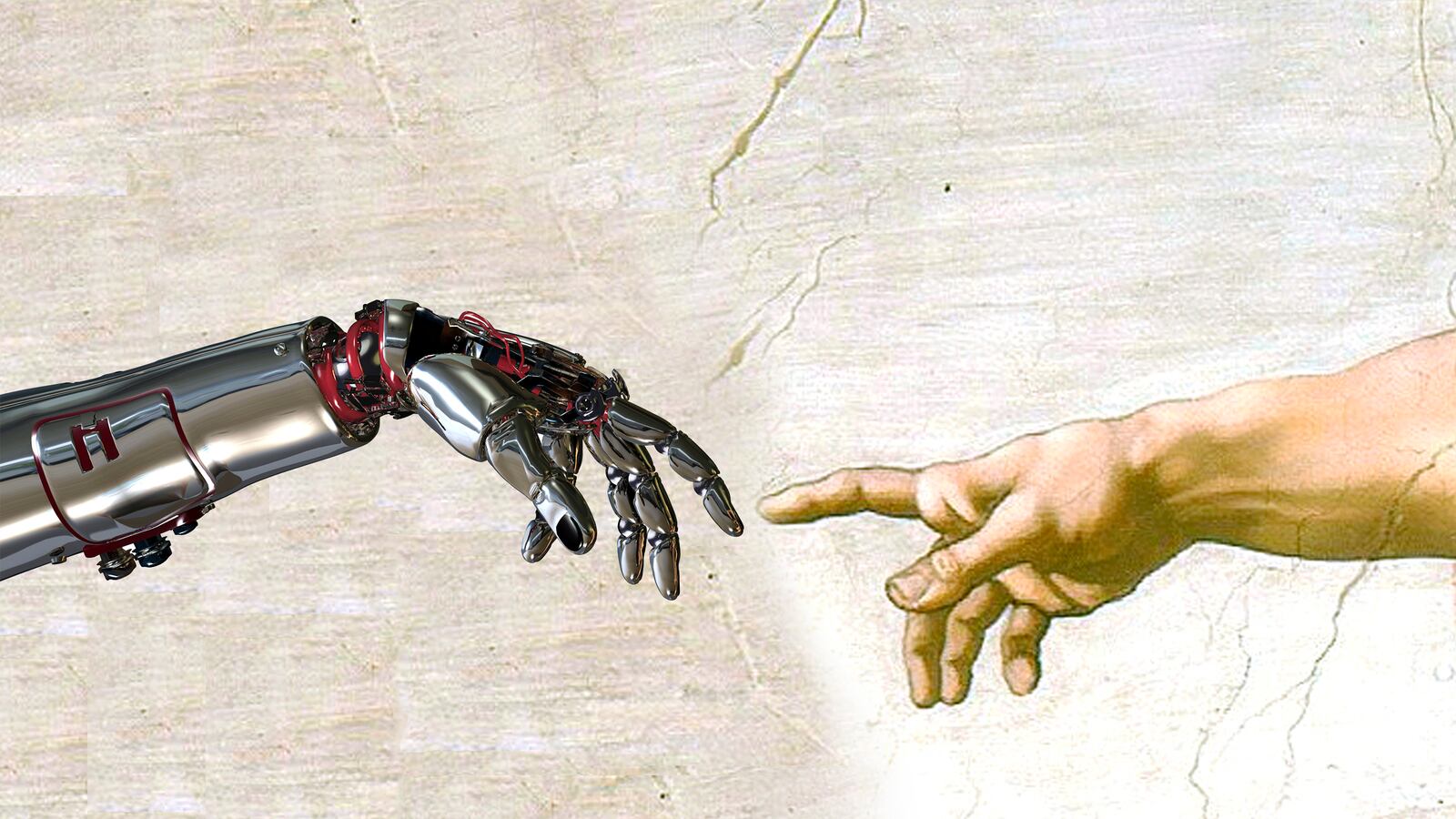

The distinction between man and machine has never been less, well, distinct.

In the last few months alone, reams of cutting edge technology able to revolutionize the human body have been released, opening up new possibilities for the way we live. This week saw the introduction of the first prosthetic hand that can successfully enable its user to feel following electrodes being inserted into the motor and sensory cortexes.

The recipient, a 28-year-old man who had been paralyzed for more than a decade, was able to sense when the fingers of the hand were touched, as well as to control it using his mind. The recipient was able to identify—when blindfolded—which finger was being touched at any one time with almost 100 percent accuracy and, when two fingers were pressed without his knowledge, the man “responded in jest asking whether somebody was trying to play a trick on him,” according to Justin Sanchez, program manager of the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). “That is when we knew that the feelings he was perceiving through the robotic hand were near-natural.”

This progression in hand prosthetics isn’t only limited to those requiring invasive surgeries. Open Bionics, winners of the 2015 Tech4Good Awards, are behind a new wave of affordable hand replacements created using 3D printing. The company seeks to provide a low cost alternative to the industry’s pricier models—a bionic hand can set you back some $100,000, compared to their $3,000 charge. “All of the advanced technology is so expensive that no one can really afford to use it,” explains COO Samantha Payne. “Bionic technology is really life changing—it enables people to have far greater independence and quality of life, and also affects their psychology. Amputees tell us that when they have a bionic hand, it helps them feel whole again.”

Where Open Bionics is really taking things in a new direction, though, is in its designs, Payne says. “We think the future is celebrating individuality—if you weren’t born with a hand, why pretend you have one? We can make you a hand in your favorite color, or have pictures of your family on it, and make it do extra things that normal hands can’t like glow at night and play music. You wouldn’t wear the same t-shirt seven days in a row—you pick out clothes that reflect your personality: It seems obvious to me that amputees want the same choice with their prosthetics.”

That sense of personalization will undoubtedly prove popular as other bionic body parts become increasingly prevalent.

Mohammed Abad, 43, from Edinburgh, Scotland made headlines last month after receiving an 8-inch bionic penis following a horrific childhood accident in which he was dragged 600 feet under a car, resulting in his appendage being torn off. After 100 operations, Abad now has two tubes along its length, which can be inflated and filled with liquid from his stomach when he presses a button located on his testicle—a procedure that began some three years ago. Created using skin from his forearm, the new addition isn’t without its glitches—Abad revealed he had an erection for two weeks following the surgery—the easily deflatable prosthetic has given him a sense of sexual confidence until then unknown. “I didn’t want to speak to anybody, I just wanted to get myself away from everybody,” he said of life before the 11-hour final operation. “But now I’ve been through it, I’m comfortable with it. It’s totally changed my life,” he told daytime TV show This Morning on Monday.

Abad’s surgery is a more preliminary version of osseointegration, a procedure being billed as the biggest bionic frontier. The process involves structures being surgically implanted into the area in which the prosthesis is needed, growing around the bone and tissue to create a more organic, integrated limb. Though it is currently not widely used for loss of limb replacement, as relatively few doctors are able to carry it out, its ability to employ prosthetics from the inside has become popular, particularly among soldiers who have gone through post-combat amputations.

It’s evident that these technologies are aimed at those who have suffered the devastating loss of a limb, but these innovative treatments pose an ethical quandary: Might people opt for voluntary removal of a hand, or leg, if it could be replaced with an even more functional bionic one? It remains to be seen, but with the field progressing at a rapid rate, such an eventuality may not be too far off the horizon.

The field of prosthetics may no longer be faced with the question of whether it can fill the corporeal gaps caused by amputations or birth defects, but whether creating a bionic body is the best option of all.