Victor Moritz: “You’re crazy!”

Dr. Henry Frankenstein: “Crazy, am I? We’ll see whether I’m crazy or not.”

—Frankenstein (1931)

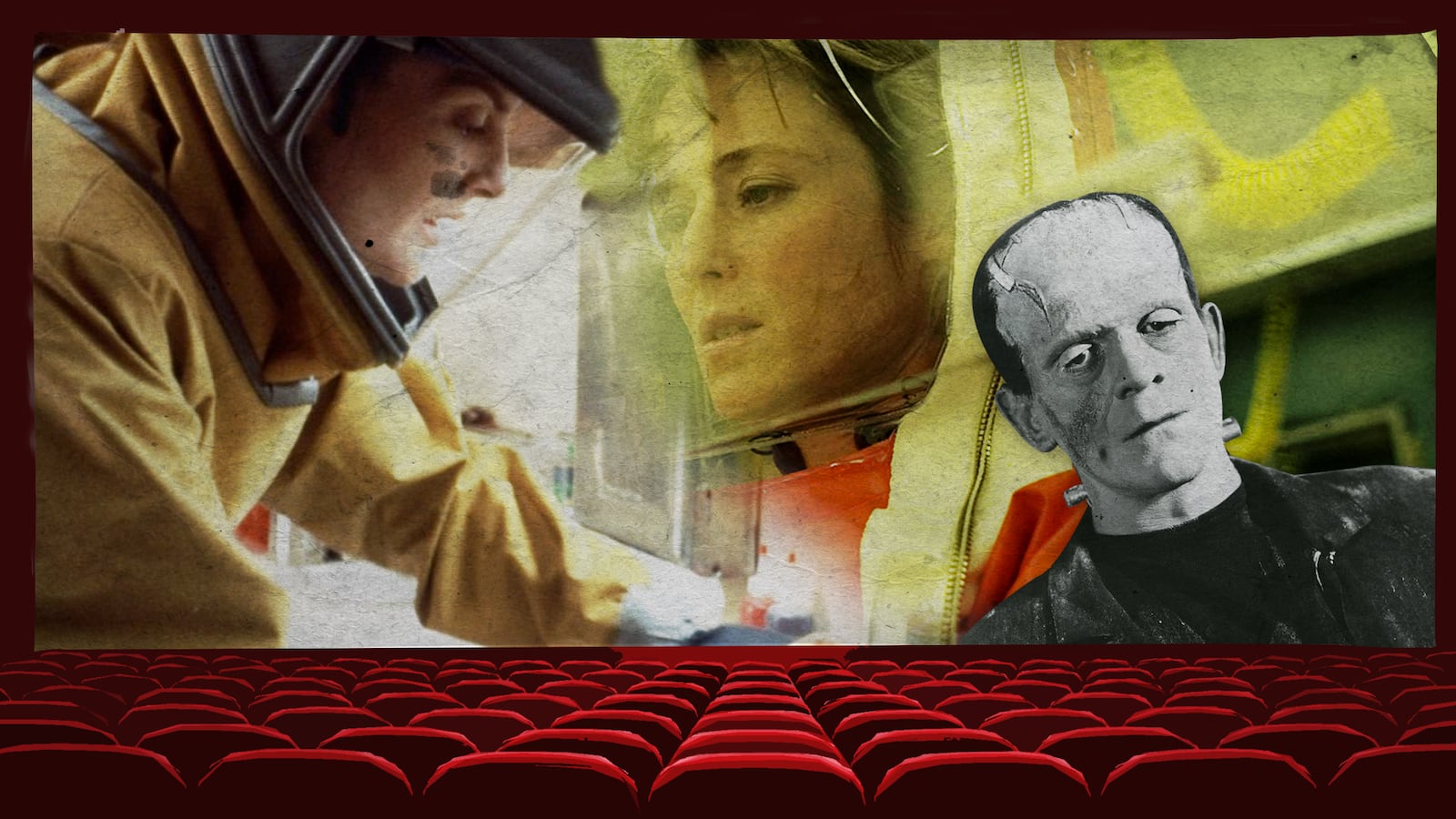

The entertainment industry educates the public about science in a different venue: movies, which not only shape opinion, but reflect some of our worst fears about science and scientists—a fear best crystallized in a single icon: Frankenstein.

The 1931 movie, based on the book of the same name written by Mary Shelley in 1818, tells the story of a scientist, Dr. Henry Frankenstein, who robs graves to procure various organs and limbs from the dead. Unfortunately, his creation, brought to life with an electrical current, was made using the brain of a murderer. Frankenstein, a literal monster created by a scientist, terrorizes the countryside.

Modern-day Frankensteins are created through something scientists call gain-of-function studies. Indeed, many scientists have now banded together to oppose them. In gain-of-function studies, microbes are altered to enhance their contagiousness. While these studies can be instructive, they also have the power to unleash uncontrollable diseases. For example, measles, mumps, chicken pox, and influenza viruses are highly contagious. Rabies, on the other hand, isn’t.

Unlike these other viruses, rabies is acquired from the bite of an infected animal, not from unseen droplets created by coughing. If the rabies virus was reengineered such that, like the respiratory viruses, it could be spread more easily, the result would be a highly contagious, uniformly fatal infection.

The gain-of-function phenomenon has been the subject of two movies: Outbreak (1995) and Contagion (2011). One was remarkable in its ability to educate the public about science; the other wasn’t. The difference between the two shows how we can be influenced to develop reasonable or unreasonable expectations about how infections are spread, how vaccines are developed, and how outbreaks are controlled.

We’ll start with the movie that got the science right.

Contagion opens with a black screen and the sound of a woman coughing. When the black screen dissolves, Gwyneth Paltrow is sitting in an airport bar in Chicago having just returned from a trip to Hong Kong. On-screen text reads “Day 2.” Paltrow is talking on a cellphone to a man with whom she has recently had sex. She is on her way back to Minneapolis, where she lives with her husband and son. The encounter with the man in Chicago, apparently, was an extramarital affair. After Paltrow coughs into her hand, the camera lingers on everything she touches: a bowl of peanuts, her credit card, the cash register.

Back in Hong Kong, another man is coughing in a subway car. On-screen text reads “Kowloon Hong Kong, population 2.1 million.” The camera lingers on a railing he has just touched. Dazed and disoriented, the man wanders onto a busy street, where he is struck and killed by a truck—but not before he gets onto an elevator full of people, the camera resting on the elevator buttons. Another man traveling by plane from Hong Kong arrives in “Tokyo, population 36.6 million,” where he collapses, seizes, froths at the mouth, and dies.

The scene shifts to “London, population 8.6 million,” as a sick woman walks into an office of graphic designers; the camera lingers on a notebook she places on her desk. In the next scene, she is lying face down in a hotel room, dead. The people who died in Hong Kong, London, and Tokyo will soon be linked to a casino in Hong Kong—each having been exposed to Paltrow.

Paltrow returns to “Minneapolis, population 3.3 million,” where she hugs her husband (played by Matt Damon) and their son. The next day, Damon picks up their son from school, where he has been coughing. The camera lingers on a door handle.

“Day 4.” Paltrow collapses in her kitchen, seizing uncontrollably. Damon rushes her to the emergency room, where, despite all efforts, she dies. Damon then receives a frantic call from his son’s babysitter; he comes home to find that his son, too, has died. Because Paltrow hugged her son on “Day 2,” the incubation period of the disease—the time between first exposure and the onset of symptoms—is two days. We also learn that once symptoms develop, death is rapid and inevitable.

On “Day 5,” we see the man in “Chicago, population 9.2 million,” with whom Paltrow has had an affair, being wheeled out of his home by paramedics, his wife anxiously running by his side. He, too, will soon die. The scene shifts to a morgue, where a pathologist pulls Paltrow’s scalp down in front of her face and removes the top of her skull. After exposing the brain and finding severe inflammation (encephalitis), the pathologist steps back in horror, certain that he has just been exposed to a deadly virus. The pathologist calls the CDC.

Kate Winslet plays the CDC epidemiologist in charge of the outbreak. Winslet predicts that the virus is spread by tiny respiratory droplets, as well as by fomites: objects that an infected person might touch, like handrails, elevator buttons, and ATMs.

The writers of Contagion then do something that no other movie about epidemics has ever done: They explain the concept of contagiousness.

On a blackboard in front of members of the Minnesota Department of Public Health, Winslet writes “Ro,” explaining that the “R” stands for “reproducibility index.” She writes “Smallpox: 3; Influenza: 1; Polio 4–6.” Then she explains that someone infected with smallpox will infect three more people every day. Winslet estimates that—given what is known about the outbreaks in Tokyo, Hong Kong, London, and Chicago—the Ro for this virus is two. The audience now understands how two infected people can quickly become four, eight, sixteen, thirty-two, sixty-four, and so on. Given that the incubation period is short, that the disease is invariably fatal, that no antiviral drugs are available to treat it, and that no vaccine exists to prevent it, the viewer also understands that this epidemic is unstoppable.

The scene shifts back to the CDC, where Contagion again distinguishes itself as the only blockbuster movie to describe the science of viruses and viral vaccines carefully and accurately. A CDC virologist, played by Jennifer Ehle, has now isolated and defined the genetic sequence of the epidemic virus, which she calls MEV-1. Ehle explains that MEV-1 is a combination of genetic sequences from two viruses: one a pig virus, the other a bat virus. Bat viruses, which can cause fatal encephalitis, aren’t spread from one person to another; they are spread only from bats to people.

However, by incorporating genetic sequences from a pig virus, this new combination virus can now be spread easily by coughing, sneezing, or even talking. (Ehle’s explanation is entirely plausible. Pigs and humans share the same viral receptors on cells that line the nose and throat.

Again, the writers of Contagion advance a sophisticated concept, accurately.) “Somewhere in the world, the wrong pig met up with the wrong bat,” says Ehle.

The next day, the CDC estimates that the MEV-1 virus has killed thousands of people and is on its way to killing hundreds of thousands. The writers of Contagion again break new ground by taking time away from usual movie fare (sex and car-chase scenes) to explain how vaccines are made. Ehle says that you could kill the virus (the way that Jonas Salk made his polio vaccine), weaken the virus (the way that the measles, mumps, rubella and chicken pox vaccines are made), or take just one of the deadly virus’s genes and clone it into a different, harmless virus (the way that the Ebola and dengue vaccines are made).

The MEV-1 virus, however, is so deadly that it immediately kills every type of cell in which it has been grown, making it impossible to weaken in the laboratory. This is another sophisticated concept. But the writers trusted the audience to understand it. Then Kate Winslet, the CDC investigator, dies from the disease (which seemed horribly unfair since she had only recently survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic).

The breakthrough comes when a virologist in San Francisco, played by Elliott Gould, finds that he can grow MEV-1 in bat lung cells that he obtained from a collaborator in Geelong, Australia. This allows Ehle to weaken the virus.

To test her vaccine, Ehle inoculates experimental monkeys and then challenges them with MEV-1. If the vaccine works, the monkeys will live; if not, they will die. The next several scenes show researchers stuffing dead monkeys into plastic bags. On the fifty-seventh attempt, however, the monkeys survive. Again, give credit to the writers for showing so many failed attempts. The scientific advisor for Contagion was Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University and an expert in the field of unusual viruses coming from unusual places. In tribute to Dr. Lipkin, the Elliott Gould character is also named Ian.

In the midst of the pandemic, society breaks down. Schools and churches empty. Banks are overrun. Grocery stores are looted. Police and fire departments disband. Trash accumulates. Airports close. The president of the United States is taken to an undisclosed location, and Congress works underground. The death toll reaches 2.5 million.

The writers of Contagion take on one more challenge that makes this film not only accurate but brave. They include a character, played by Jude Law, who touts a homeopathic cure for MEV-1 called Forsythia. On his blog (TruthSerumNow), which has more than two million followers, Law shows himself coughing and haggard, pretending that he, too, is now infected. Then he takes Forsythia. During the next few days, Law appears to recover. Convinced that a cure now exists, people break into pharmacies trying to get Forsythia. Law, who makes $4.5 million from his bogus cure, is a direct slap in the face of dietary supplement hucksters.

The action shifts back to the CDC, where Ehle explains how the MEV-1 vaccine will be tested, mass produced, and distributed, again accurately. In response, Law appears on CNN decrying scientists who have urged vaccination. Law argues that the vaccine hasn’t been tested long enough and that we shouldn’t trust government and pharmaceutical company scientists—a common refrain from anti-vaccine activists. When Law is later found to have faked his illness, he’s arrested for securities fraud, conspiracy, and manslaughter. While this might seem over the top, consider that homeopathic doctors in Canada sell nosodes: homeopathic vaccines. Homeopaths make these vaccines by taking a virus and diluting it in water to the point that it’s not there anymore. In other words, they’re selling water as a vaccine. Given that some people could suffer and die from vaccine- preventable diseases as a consequence, these homeopaths could reasonably be charged with the same crimes as the Jude Law character in Contagion.

Unlike Contagion, Outbreak, also featuring the potential dangers of gain-of-function studies, sacrificed accuracy for drama. Outbreak opens in a war zone in Zaire. The year is 1967. Men in hazmat suits are walking through a village where an unknown illness has killed forty-eight people. Many others are dying, blood coming out of their mouths and eyes. The men in hazmat suits assure those who are dying that everything possible will be done to save them. A few hours later, a plane is seen flying overhead; the men rejoice, assuming that medicines and supplies are on their way. Joy turns to horror when they realize that the parachute isn’t carrying supplies; it’s carrying a bomb that destroys the entire village. Monkeys run from the wreckage.

Thirty years pass.

Next we learn that the United States is preparing to use this deadly African virus as part of a germ-warfare program. (Here, art imitates life. Both the United States and Russia have developed programs to put plague bacteria and hemorrhagic fever viruses into bombs and missiles. Richard Nixon ended the biological weapons program in 1969 and ordered all existing stockpiles destroyed.)

The scene shifts to the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in Fort Detrick, Maryland, where bio- safety hazards are explained:

- Level 1, mild risk: pneumococcus, salmonella.

- Level 2, moderate risk: hepatitis, influenza, Lyme disease.

- Level 3, high risk: anthrax, HIV, typhus; vaccinations required (which would have made a lot more sense if vaccines actually existed to prevent HIV and typhus).

- Level 4, extreme biohazard, maximum security: Ebola virus, Hantavirus, Lassa virus; no known cures or vaccines.

Soon we learn that another outbreak has occurred in Zaire. Several scientists, played by Morgan Freeman, Cuba Gooding Jr., Dustin Hoffman, Rene Russo (Hoffman’s ex-wife in the movie), and Kevin Spacey, are dispatched to control the out- break and find its cause. “Looks like we have a Level 4,” says Freeman. “I’m flying to Zaire.”

The scientists arrive to find that the symptoms are the same as those in the 1967 outbreak: bleeding from the eyes, ears, mouth, and rectum, accompanied by liquefaction of internal organs—in short, a hemorrhagic fever virus like Ebola. (For the record, hemorrhagic fever viruses don’t actually liquefy internal organs.

Outbreak is based loosely on Richard Preston’s best-selling novel The Hot Zone, which tells the story of the Ebola virus, a deadly pathogen that first appeared in Zaire in 1976, killing three hundred people.) Bodies are lined up in rows, waiting to be burned in one of several fires dotting the village. One child is riddled with blisters, crying, and sick—his two dead parents lying beside him. Seeing this, Cuba Gooding Jr. vomits into his hazmat suit. Because the outbreak occurs in the Motaba River Valley of Zaire, it’s called the Motaba virus. We learn that the disease is invariably fatal and that no one infected lives more than two days. “This is the scariest son of a bitch I’ve ever seen,” says Hoffman.

In the next scene, a monkey that had escaped from the village is trapped and put on a ship headed for Seattle.

Back at Fort Detrick, scientists have isolated the virus, which by electron microscopy looks exactly like the Ebola virus. We learn that the virus is so deadly that it can reproduce itself in cells in only one hour. (Unlike bacteria, viruses can grow only inside cells, which usually takes two to three days. One hour would be impossible.)

The monkey that was captured in Zaire ends up in a Biotest Animal Holding Facility in San Jose, California, where it is promptly stolen by Patrick Dempsey and sold to the owner of Rudy’s Pet Shop in Cedar Creek. Both Dempsey and the pet-store owner later die from the disease—but not before Dempsey releases the monkey into the forest surrounding Cedar Creek.

People in Cedar Creek start dying from the Motaba virus. The city is put under military control; no one can enter or leave. Then something unusual happens (not that all of this hasn’t been unusual enough). The Motaba virus infects a man who has been hospitalized for weeks following a car accident—a man who was never exposed to the monkey. How did he catch the virus? Hoffman realizes that the virus has mutated, now easily spreading through hospital air ducts (this is the gain-of-function part).

In an effort to control the outbreak, the military decides to bomb Cedar Creek, killing all twenty-six hundred of its residents. The bombing mission is called Operation Clean Sweep. When Dustin Hoffman finds out about the proposed bombing, he knows that the race is on to find a lifesaving antiserum that will save Cedar Creek’s citizens, which now includes his ex-wife (they’ve recently reconciled).

Hoffman believes that if he can find the monkey that started the outbreak, he can make the antisera he needs. Much of the movie is now spent trying to find that darn monkey, including one dramatic helicopter chase scene in which the military tries to shoot Hoffman out of the sky. (Hoffman doesn’t really need the monkey. He’s already isolated and grown the virus. All he needs now is to inoculate the virus into one of any number of animals and make his antisera. Forget about the monkey.) Once the monkey is in hand, Hoffman instructs Cuba Gooding Jr. to take it back to the lab, determine which antibodies are neutralizing the mutant virus, synthesize those antibodies, and make several liters of life-saving antisera. Assuming everything goes well, Hoffman’s task should take about a year. Cuba Gooding Jr. does it in a little less than a minute. (Now I understand why people are angry that we still don’t have an AIDS vaccine.) Then, in one final if-only-this-were-true-in-real-life flourish, after receiving the antiserum, Rene Russo improves in thirty seconds.

Although it is no doubt out of their comfort zone, scientists should try to do what Ian Lipkin did in Contagion: get involved in movies about science, whether fiction or nonfiction. It’s worth it. For example, starting in the 1950s, formal relationships between NASA and the American Medical Association and the movie and television industry have been shaping our perceptions of astronauts and doctors. Indeed, NASA, by consulting on movies like Apollo 13 (1995), Armageddon (1998), Mission to Mars (2000), and Space Cowboys (2000), was able to maintain its positive image despite the Challenger disaster of 1986.

Other examples abound. The participation of the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Twister (1996), the United States Geological Survey in Dante’s Peak (1997), and Federal Express in Cast Away (2000) led to better perceptions of those organizations. One group that could clearly benefit from a better working relationship with the film industry is vaccine makers. No group, it seems, has a worse reputation than pharmaceutical companies. Indeed, in the movie The Constant Gardener (2005), a pharmaceutical company (presumably using its black ops division), murdered people who had discovered a deadly side effect from its new drug. This plot was believable to most viewers.

The movie The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) provides one final inducement for scientists to serve as consultants. The paleontologist Jack Horner, who consulted on the film, was in the midst of an argument with a colleague about a particular concept. Horner later noted that one of the actors who gets eaten by a T. rex in the film bore “a striking resemblance to a guy who argues with me a lot.”

“If you are ever arguing with someone,” warns Horner, “don’t let them be the advisor on a movie.”

Excerpted from Bad Advice: Or Why Celebrities, Politicians, and Activists Aren’t Your Best Source of Health Information by Paul A. Offit, M.D. Copyright (c) 2018 Paul A. Offit. Used by arrangement with Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.