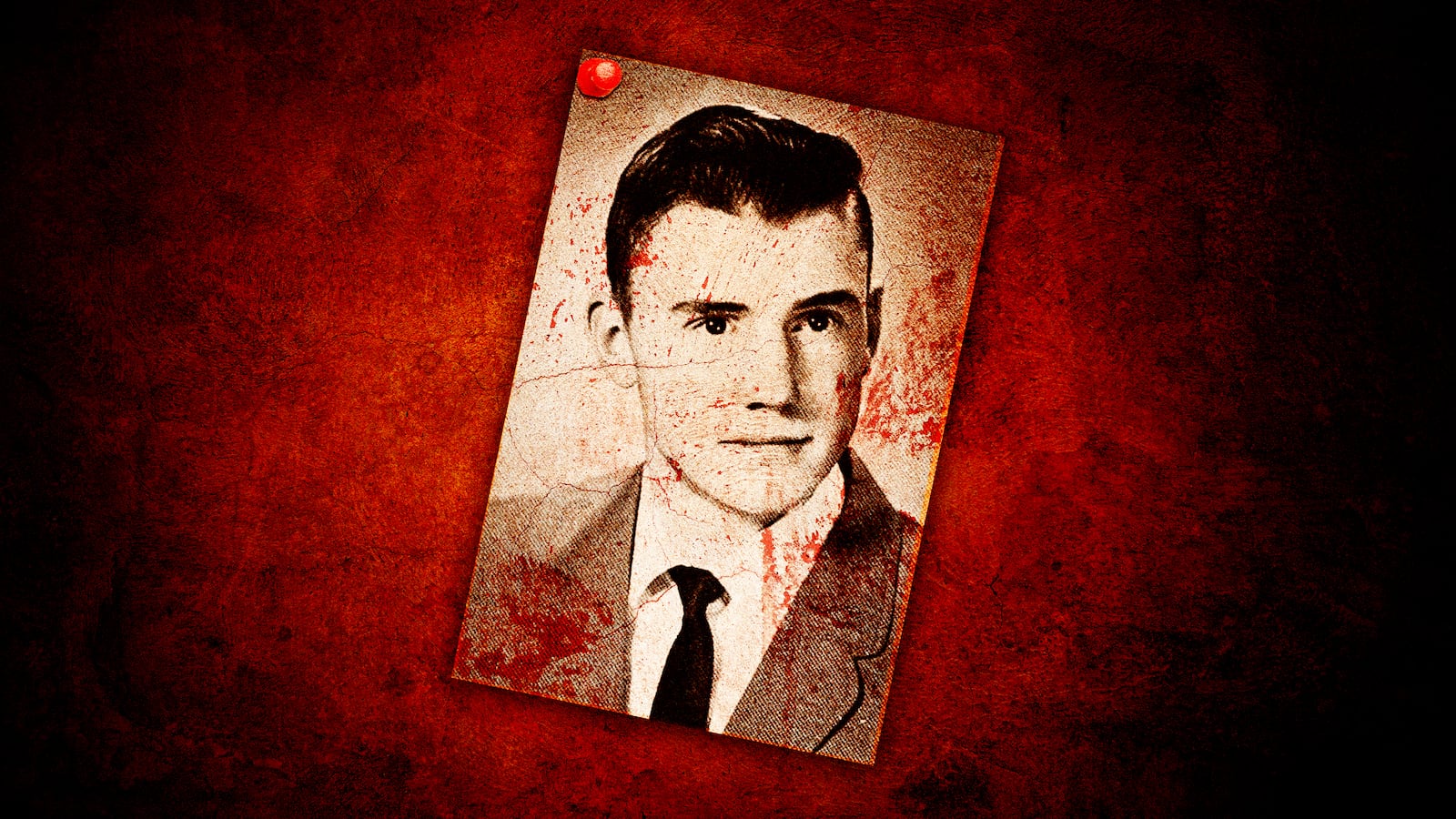

He was a small-town guy from Manhattan, Montana, population 900. A former Boy Scout, Marine sergeant during the Vietnam War, a carpenter, and a property owner who renovated old houses. David Meirhofer was friendly enough, but he didn’t talk much, and was a bit socially awkward—a 24-year-old virgin who didn’t smoke or drink, “loved to talk cop,” and whose favorite movie was The Sound of Music.

Meirhofer also had a terrible secret: he was a serial killer who had murdered four people, chopped two of them into small body parts, burned them in a trash barrel outside an abandoned ranch, then wrapped up some other parts, labeled them “deer meat,” and stored them in his freezer.

If this sounds like a “typical” serial killer story, the kind we’ve become all too familiar with thanks to Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, et. al., and the numerous real-life and fictional depictions in books, movies, and on TV, well, in a way, it is. But the 1974 Meirhofer case had this singular distinction: When the local police were stumped in their search for the murderer, they appealed to the FBI for assistance, making it the first instance in which the new science of criminal profiling was used to help solve a crime.

“Everybody initially assumed it was an outsider,” says Ron Franscell, author of ShadowMan: An Elusive Psycho Killer and the Birth of FBI Profiling, a book about the Meirhofer murders and the profiling connection. “The overwhelming number of tips they got were about people who weren’t from there. The remoteness of Western Montana played a role, because law enforcement in that time in that place, they were limited in their training and their budgets, and it required the kind of effort that a bigger city would have been more naturally able to do. In that county they had only dealt with one or two murders in a decade. They weren’t prepared for this.”

Enter Patrick Mullany and Howard Teten, who were teaching a course at the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Va., called “Psychological Profiling.” Mullany had experience lecturing on criminal psychology, while Teten taught a seminar on the relationship between a crime scene and offender characteristics. They had decided to team up in a course that would present the physical characteristics of the crime scene and the criminal, then explore the psychological disorders that were most likely indicated. The problem was, this was still J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, and the big boss, who thought that what Mullany and Teten were doing was hokum, made sure to keep them on a very short leash.

Howard Teton

FBI“Profiling today is based on this enormous database of information accumulated over the past 50 years,” says Franscell. “Mullany and Teten didn’t have that road map, they were making interesting guesses. Early on it was true, and is to a certain degree today, the boots on the ground didn’t trust it. They thought the way to go was knock on doors, and here were guys saying we can read their minds from looking at the crime scene.”

Although Meirhofer had been a suspect since the beginning of the investigation, he was not easy to catch. He passed lie detector and truth serum tests, but eventually was arrested thanks to his failure to pass a voice printing “lineup’ based on threatening phone calls he had made to one of the victim’s families. But even though Mullany and Teten had a hand in narrowing down the pool of suspects—they initially believed, correctly, the killer was a schizophrenic sadist with a sexual element—Franscell emphasizes that profiling “works best when they have a lot of evidence. The worst time is when they have no evidence, but even the absence of evidence is evidence. And profiling doesn’t work like it plays on TV. They’re generally called in to deliver a kind of short course in forensic psychology, and look at a case and say, ‘Here’s some things you should look at.’ They deliver a report, eat lunch and go back to Quantico.” So it was the criminal investigation that eventually brought Meirhofer to justice.

David Meirhofer is placed under arrest in 1974.

Mattconz/Wikimedia CommonsShadowMan calls the time of the Meirhofer murders the “golden era” of serial killers, a period when high profile cases like those of Gacy, Bundy and the Green River Killer captured the nation’s attention and helped lead to the deluge of serial killer media obsession that continues into the present day. “The criminal mind has always fascinated us,” says Franscell. “When especially deviant crimes happen, our rational minds want to put things back in order. So our first question is ‘Why?’ We want to understand the threats that are out there. I don’t think our fascination has changed [over time], our media has changed. It allows us to immerse ourselves in lurid details from a distance from this real pain that happens.”

And despite evidence that the U.S. might be the serial killer capital of the planet—this country has three times more serial killers than any other nation, and two-thirds of all known serial killers—Franscell believes statistics like these stem from the fact that “we generally have better trained and better funded law enforcement and forensic sciences, which means that, on the whole, we find more serial killers.”

Franscell’s book is, not surprising coming from an author who has specialized in crime novels and true crime works, a breezy and fascinating read. But ultimately it is extremely frustrating, which is not the author’s fault. It seems Meirhofer was willing to confess to two murders the investigators knew nothing about, if they took the death penalty off the table. So in a long interrogation, of which Franscell includes a good portion in ShadowMan, the police ask a lot of questions about how Meirhofer committed the killings, what he did with the bodies, etc., but never ask him why he did what he did. Their intent was to come back the next day for further questions, but six hours after the interrogation was over, Meirhofer hanged himself in his cell, leaving his motivations a total mystery.

“I agree about the frustration of not knowing more,” says Franscell. “[The interrogation] was an attempt to get him to confess to two murders they didn’t know about, and they rushed it so they could nail it down as quickly as possible. They knew they were going to come back and ask more questions, but unfortunately, Meirhofer exercised his last act of control by killing himself.”

This was doubly frustrating because it was later learned that Meirhofer’s younger brother Alan was a serial child rapist, suggesting there was something going on in the boys’ background that created these criminals. But a sister who was interviewed after the fact, says Franscell, claimed “there was no physical or sexual abuse” in the family. Franscell thinks Meirhofer was possibly conflicted about his sexuality, and “in 1960s Montana, being gay, you could be judged in unfathomable ways by people you know. Was that enough to create this rage? I don’t know.”

Ultimately, ShadowMan is, says Franscell “about perverse love, desperation, rage. I thought of ShadowMan as a novel that I had absolutely no control over what happens. We have another example of evil out there, and we have added to the possibilities of what it looks like.”