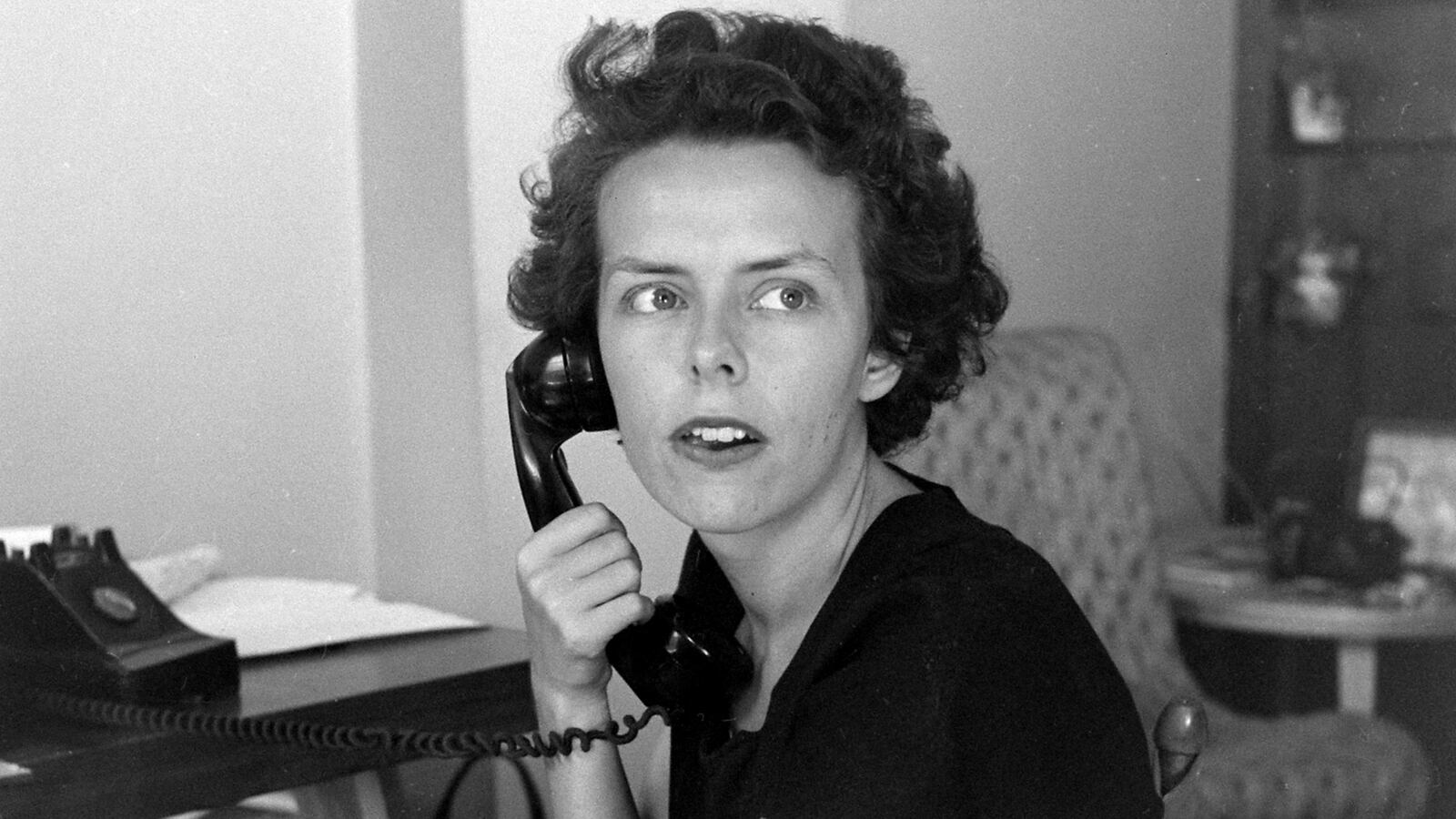

Eileen Ford’s eye for beauty was amongst the most influential of the 20th century. Over 46 years at the helm of Ford Models, she fostered the talents of hundreds of the most recognized and admired faces, icons that included Christy Turlington, Lauren Hutton, Carmen Dell’Orefice, Christie Brinkley, Beverly Johnson, Cheryl Tiegs, and Suzy Parker. She represented Ali McGraw, Dovima, Jerry Hall, Shalom Harlow, Peggy Moffit, and Penelope Tree.

She did not, however, represent 1960’s uber-nymph Twiggy, who once said of Ford, “she scares me shitless.”

Yes, she had an eye. She also had an attitude.

In Model Woman: Eileen Ford and the Business of Beauty, biographer Robert Lacey affectionately describes his subject’s “sublime lack of self-doubt.” Another attribute, neatly put: “solid gold egotism.” She was charming, temperamental, cunning and maternal; she was either loved or hated—although neither mattered to her. It was in part this mix of qualities that enabled Ford and her husband Jerry to transform the modeling business and create a new caliber of fashion mannequin. As Lacey explains, “The title ‘Ford model’ carried a cachet all its own. Ford models were seen as the aristocrats of their profession: thighs that stretched for miles, and expectation of blondeness, though not invariably so; and a general impression of extra sparkle, height and slenderness—stature, in every sense of the word, including mental discipline and punctuality.”

Lacey, who claims a specialty in biographies of royals, handles his subject with good humor. Ford can be coy: of model Janice Dickenson, she says, “I’m an Aries. We try not to mention unpleasant things.” She can also be raucous: Of the statuesque Veruschka she once told an employee, “Get rid of the big Kraut! I don’t like the cut of her jib.” Like an indulgent relative, Lacey sees Ford’s shortcomings and admires her nonetheless, allowing readers to do the same and setting the perfect tone for this high-powered page-turner.

Ford’s confidence began at her beginnings. Her parents, Nathan and Loretta Ottensoser, worked together running a successful debt-collection agency. They had waited six years for her, the first of their three children. “I was the cure for cancer,” she recalled, “the answer to everything. So far as they were concerned, I was the most talented child ever born—the answer to all the world’s problems.”

Indeed, young Ford’s life in the wealthy enclave of Great Neck, New York seemed lifted from a wholesome all-American playbook. She was outgoing and ambitious, but not an intellectual. In high school, she planned dances for her sorority. (In 1938, the family name changed from Ottensoser to Otte, obscuring their Jewish roots. Astonishingly, Lacey says that they did so in order for Ford to avoid the “Jewish quota” when applying to college; she wasn’t smart enough to compete for the slots reserved for Jews.) While attending college at Barnard she was banned from assemblies after attending a talk by Eleanor Roosevelt and laughing uproariously at her “strange” voice. No problem, Ford thought, as this “meant that I could go off to Tilson’s drugstore and meet all the boys from Columbia.”

Ford modeled a little, her fresh-faced collegiate looks appropriate for the new teen-centric issues of publications like Mademoiselle. And she was a magnet for men as well—during the World War II years, she claimed to have been engaged 11 times. “I had all these fiancés, but I was not evil,” she explained. “It would have been different if they had not all been going off to war...I just wanted to make their lives just a bit sweeter.”

And then came Jerry Ford. “When Jerry stood up in his uniform, he was so handsome I almost fainted,” Ford recalled. In 1944, after three months of courtship, Ford hopped a train to follow the unsuspecting naval ensign to San Francisco, leaving only a brief note to her parents. “I love him and there doesn’t seem to be much I can do about it except marry him,” she wrote, “so I’ve gone to do just that.” Although Jerry had no idea she was on her way, soon after her arrival they married at City Hall. He was 19. She was 22. Of their whirlwind nuptials he once told a friend, “Did you ever try saying no to Eileen?”

The modeling agency started casually, with Ford organizing the business for top model Natalie Nickerson, who then set out to recruit more professional beauties. Ford Models opened in 1947, originally in partnership with Nickerson (a fact only uncovered as Lacey researched this book). In 1948, Life magazine ran a spread featuring the “Family-style” agency, and put the business on the map. The Fords made a great team. “Eileen had the eye that recruited the quality, and Jerry made sure that people paid properly for it,” writes Lacey. (At the time, the highest paid model in the world was earning $40 an hour. By the 1990s, Linda Evangelista famously quipped that “we don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.”) “Jerry introduced cancellation fees, fitting fees and weather permitting fees,” Lacey writes. Off hours they loved to entertain, and Ford—always determined to make a situation bend to her will—would signal the party’s end by running the vacuum cleaner.

From the early 1950s to 1977, the Fords reigned supreme. While not unchallenged, they were generally secure in their primacy. They grew their stable of models, their relationships with agencies around the globe and, most importantly, their reputation. This was important to Ford, who brought many of her models to live at the Ford townhouse on 78th Street, where she could teach good manners and closely monitor intake at the dinner table: “Is that four string beans on your plate? … Make it three.” Rules there were strict. In the mid-1970s, when Jerry Hall began dating Mick Jagger, she had a midnight curfew.

In 1977 a true nemesis finally appeared, which “came as a big shock to [Ford],” recalled her nephew William Forsythe. “She had no natural predators for many years,” he explained. Befitting a feud in the land of appearances, John Casablancas of Elite Model Management was perfectly cast as the agency’s archenemy. If the Fords epitomized post-war optimism and family life, Casablancas was a walking embodiment of the sexual revolution. He sported a thick dark mustache, a mop of dark hair and a penchant for “boffing” his models. The Elite logo, in fact, “was inspired by the image of two testicles nestling on either side of an upright phallus.”

Casablancas, who opened his first agency in Paris in 1969, originally revered the Fords. He considered Ford “the Empress, Catherine the Great,” and said of her and Jerry, “they gave off this aura together of ‘This is how things should be.’” His Parisian agency even successfully partnered with them. But his unforgivable offense was to open offices, secretly and without sanction, in New York City. It was impolite, simply not done.

The ensuing “Model Wars” were essentially a battle between old ideals and new. It was the established agency that followed the rules versus the rude upstart. There were vitriolic meetings and there were lawsuits. Models jumped from agency to agency and then back again. Each side had wins and losses. Stylist Shelly Promisel told Lacey, “There’s no doubt that the Model Wars were good for the whole of the U.S. fashion business, and for New York in particular. The publicity brought such attention to U.S. photographers, makeup artists, stylists and hairdressers—everyone involved. The rates paid to models went sky high. Girls that cost seven hundred and fifty a day were charging fifteen hundred dollars a few years after Elite arrived.” Lacey covers the Model Wars with all the enthusiasm and detail this fascinating episode deserves. It’s a magnificent example of the upheaval caused by shifts in the cultural bedrock.

For nearly half a century, Ford was a fundamental cog in the fashion infrastructure, often initiating change and sometimes at the mercy of it. In 1970, Life magazine bestowed her the title of “godmother” of modeling; she was to continue godmothering at Ford for another 23 years. Lacey brings his narrative to a close soon after Ford and Jerry retired in 1993. This seems appropriate for a biography of a woman who once declared, “the opposite of work is death.” It is, after all, a book about how woman shaped an industry to meet her own standards. “If you want to do something, you can’t go on talking and talking about it,” Ford once explained. “That’s a very boring song. So you just do it.”