As a trial judge in Washington, D.C., Eric Holder was known as a tough sentencer, a long-ball hitter in courthouse parlance. It was the early ’90s and the city was in the grips of a crack-fueled murder epidemic with homicides rates pushing 500 a year. Holder was unapologetic about throwing the book at violent criminals who he believed were victimizing their own communities. One defense lawyer dubbed him “Hold’em Holder” for his unsparing sentences.

And yet during the same period he was increasingly unsettled by another criminal-justice trend—one that he had little control over. Low-level, nonviolent drug offenders, even in relatively liberal Washington, were coming under a harsh, inflexible regime of mandatory minimum sentences. Holder and his fellow judges had little choice but to send hundreds of young men to the notorious Lorton Correctional Facility for long prison terms, where they were schooled in criminality and received little if any treatment for their addictions. He felt like a cog endlessly pushing predominately black young men through a callous machine that did nothing to address the underlying social ills that led to crime in the first place.

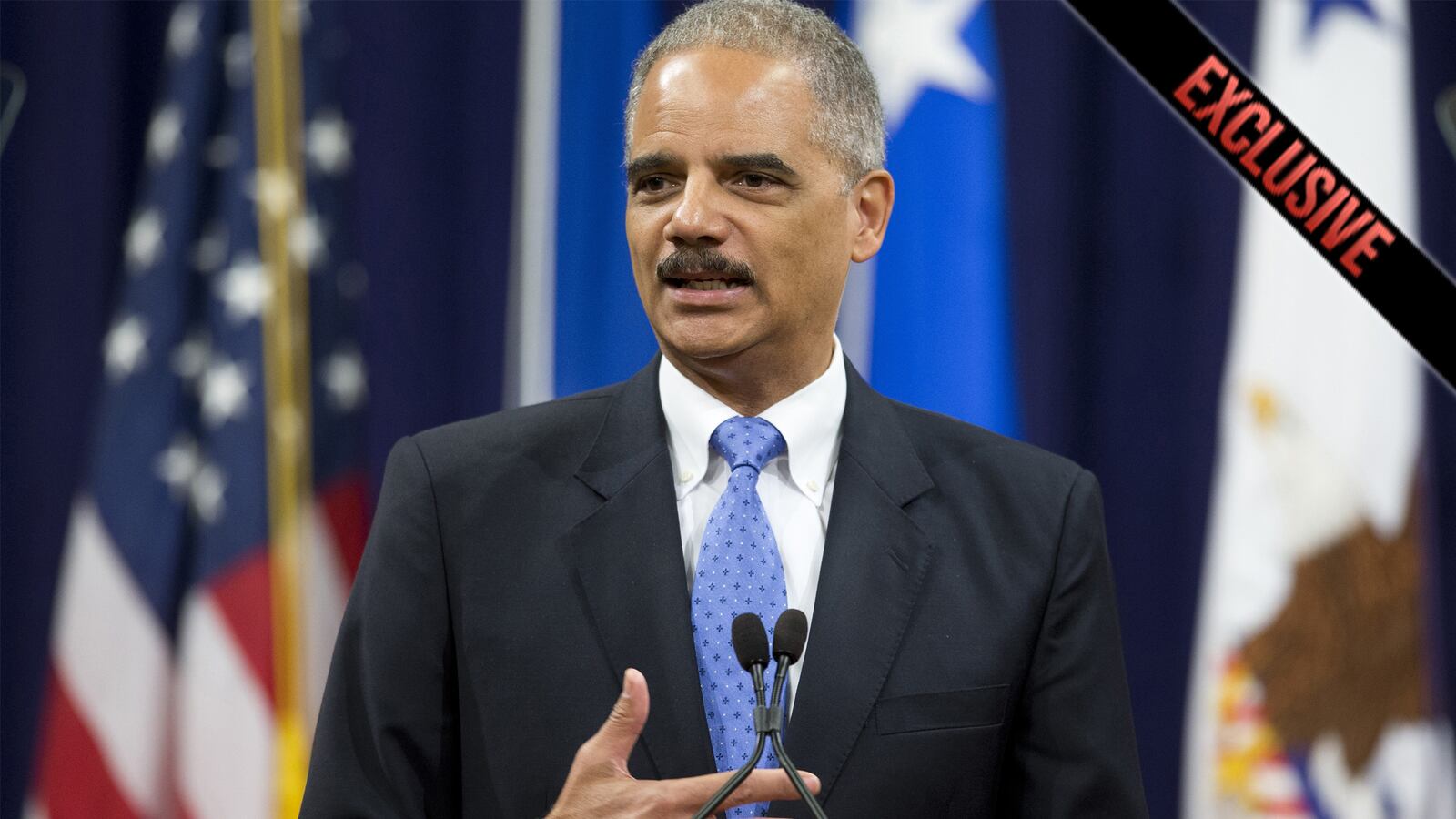

“I saw an ocean of young men come before me, who should have been the future of my city, destined to serve long jail terms and then spend their lives dealing with all of the negative consequences of being an ex-offender,” Holder recalled to The Daily Beast in an interview this week.

Holder had come of age as a judge and a federal prosecutor at the height of the country’s tough-on-crime ethos. The trend had begun with Richard Nixon’s War on Crime, and accelerated under the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, when conservative academics were spinning theories of irredeemable “super-predators” and positing that IQ, genetics, and even race preordained criminal behavior. The conclusion of such thinking: criminals could not be deterred nor rehabilitated, but incarcerating them for long periods of time was the surest way of lowering crime rates.

As a trailblazing African American in law enforcement, Holder was attuned to the growing inequities in the criminal-justice system. But more than that, he saw an irrational system that trapped young men in an endless cycle of poverty, crime, and incarceration, a school-to-prison pipeline that further frayed the social fabric of the very communities the American justice system should have been helping. As he rose through the ranks of federal law enforcement, eventually becoming the country’s first black attorney general, Holder worked within the system to reform it. Never a renegade or table-pounder, he pushed for incremental change through quiet persuasion. During most of that time, his efforts were met with more frustration than progress. Republican politicians rode to election year after year on tough-on-crime planks and Democrats, fearful of being tagged as soft, went along for the ride.

But more recently, as crime rates have plummeted and exploding prison populations have stretched state coffers, the political climate has become more receptive to reform. Holder saw an opportunity to act on a set of principles he has believed in for the better part of a quarter century. At a widely publicized speech to the American Bar Association on Monday, Holder announced a set of policy changes that puts the federal government squarely behind a more progressive vision of how justice should work in America. (Interestingly, red states like Texas and Kentucky have actually led the way with more liberal sentencing policies aimed at reducing prison overcrowding.)

The centerpiece of the shift was a unilateral move to stop charging low-level drug offenders with crimes that carry stiff mandatory minimum sentences. He directed U.S. attorneys to withhold from criminal complaints the specific drug amounts that trigger the harsh penalties. By doing so, prosecutors, judges, and juries will have far more discretion in determining sentences. He also announced new compassionate-release policies for elderly and sick prisoners who pose little threat to society. Holder unveiled an initiative to identify drug offenders who can be diverted to treatment programs and other alternatives to incarceration. And in an effort to reduce recidivism, Holder announced a new federal emphasis on “prevention and reentry,” identifying ways to make it easier for former prisoners to rejoin society.

The new policies are aimed at easing overcrowding in the federal prison system and identifying more cost-effective and just strategies for tackling the nation’s crime and drug problems. For Holder, the speech was also a cri de cœur against a system that he believes imposes massive moral and human costs on the United States, which makes up 5 percent of the world’s population but nearly 25 percent of its prisoners.

“Too many people go to too many prisons for far too long and for no truly good law-enforcement reason,” Holder said in the speech. “We cannot simply prosecute or incarcerate our way to becoming a safer nation.”

The speech was the opening shot in a more ambitious effort under consideration at the White House to bring even more reforms to the criminal-justice system. Two senior administration officials tell The Daily Beast that President Obama will likely give a major speech addressing these issues before the end of the year. Among the questions being examined, according to these sources, is whether and how to tackle racial disparities in sentencing. A recent study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which Holder cited by in his speech, found that, on average, black men receive sentences that are 20 percent longer than those received by white men for equivalent crimes.

Some critics have suggested the reforms announced by Holder are too little too late. With federal prisoners comprising only 200,000 of the total U.S. prison population of nearly 2 million, only a relatively small number of future offenders may benefit from the new approach. (Offenders will have to meet a series of requirements to be eligible for the more lenient treatment; among them, that they have no significant ties to cartels or drug gangs, that their conduct did not involve violence, and that they have no significant criminal history). Holder’s aides say the new rules, which have already gone into effect, will significantly slow the growth of the federal prison population over time. Moreover, they argue the shift will begin to restore faith in a system that has lost credibility with millions of Americans, particularly minorities.

Some commentators have also suggested that the announcement amounted to a legacy play for an attorney general who has had a sometimes rocky tenure, stemming from sensitive counterterrorism decisions and other controversies. Those who know Holder well bristle at the idea that an issue so near to his heart would be cast as an effort to buff his image before he leaves government, as he is expected to do in the coming months.

“This is the culmination of work he began years ago as a judge, a prosecutor and an African-American man in this society who wanted to make the system more humane, fair, and effective,” says Timothy Heaphy, the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Virginia, who has known Holder for years and was part of a committee of federal prosecutors that advised him on the new policies.

Throughout Holder’s life and professional career, he has managed to stay rooted in communities of need. He grew up in a stable family in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Queens, New York, where his mother’s firm but compassionate hand kept him on a narrow path. During college and law school, he tutored disadvantaged kids in Harlem. And when he became a parent, Holder became active in Concerned Black Men, a youth-mentoring program.

As a judge in D.C. Superior Court, he witnessed the city’s rebellion against sentencing policies closeup. Time and again, juries refused to convict drug defendants, even in cases where there was overwhelming evidence of guilt. Many of his cases ended in hung juries. As was his habit, Holder would ask the jury to stay behind so that he could probe their reasoning. Invariably, Holder recalls, the juror who’d held out against conviction would say, “I know about these sentences and I’m not going to send another young black man to prison.” It was a sobering view of how drug policies were corroding trust in the criminal-justice system.

Holder’s sense of powerlessness to change the system spurred him to leave the bench.

“I felt like I was a referee in the middle of the game and I wanted to be a player,” says Holder. “I wanted to be a part of the solution.” So when Bill Clinton was elected president in 1992, Holder applied to be Washington’s U.S. attorney and he got the job. Holder wasted little time. One of his first moves was reversing his Republican predecessor’s policy of bringing relatively minor drug cases into federal court, where he could get tougher sentences. (In Washington, the U.S. attorney prosecutes cases in both federal court and local court.)

But it was another Holder initiative that opened his eyes to how little trust significant portions of the city had in the justice system. Modeled after community policing, Holder pioneered a “community prosecutions” program that brought his prosecutors into neighborhoods all over the city. Aimed at improving ties between law enforcement and local residents, Holder himself regularly visited the city’s most disenfranchised neighborhoods. And whether he was addressing a group in a church basement or trying to comfort a mother on a stoop about her wayward son, Holder was hearing about a system that had gone wrong in fundamental ways. “People would say ‘We want these neighborhoods cleaned up, but why do you have to send all these people away for 10 years?’” Holder recalled. “‘But why can’t you just get these people straight?’” using the local vernacular for getting them off drugs. Holder was listening and was able to help establish the first federally backed drug court in Washington, where low-level offenders could be diverted from prison to a treatment facility.

Soon the Clinton administration began noticing Holder’s innovations and identified him as a rising star. In 1997, Attorney General Janet Reno tapped Holder to be her deputy, making him the highest-ranking African American in federal law enforcement. But Holder was way ahead of his own administration when it came to criminal-justice reforms. Bill Clinton had moved the Democratic Party to the center and was not about to cede any ground on a hot-button political issue like crime. He backed a major crime bill that left the most far-reaching mandatory minimum sentences in place and threw in a few federal death-penalty provisions for good measure.

One issue in particular raised the hackles of civil-rights and defendants’ rights groups: the 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, which had a disproportionately severe effect on blacks. With an African American in the second-ranking position at the Justice Department, the groups were hoping they would be able to significantly narrow the disparities. Holder was sympathetic, but he was unable to get the White House’s support to back the reform.

In 2000, Holder left government for a Washington law firm, his first foray into the private sector. Though he kept his hand in crime policy, sitting on the boards of public interest organizations and handling pro bono cases, he no longer had the power to effect change.

But a few years later, he met an up-and-coming young Senate candidate from Chicago. Holder and Barack Obama hit it off immediately and among the issues they bonded over was what they saw as an urgent need to reform the criminal-justice system. As a community organizer on Chicago’s South Side, Obama had seen the dehumanizing effects of harsh sentencing policies on a generation of black males; later, as a state senator, he’d pushed through legislation aimed at curbing racial profiling in police departments.

“My experiences and observations were consistent with what he saw,” says Holder. “Low-level offenders were getting caught up in the system, selling drugs to support a habit in astounding numbers and where treatment was close to nonexistent.” One of Obama and Holder’s first substantive conversations was about the injustice over the disparity in sentencing between crack and powder cocaine.

After Obama was elected president in 2008, he selected Holder as his attorney general. Pushing more lenient sentencing polices was not going to be the White House's priority straight out of the gate. Holder, for his part, was quickly preoccupied with national-security controversies, from the challenges of closing the prison at Guantanamo Bay to the ill-fated effort to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in New York City. And Obama, as the first black president, seemed leery of tackling an issue with such clear racial overtones. “In the first term, unfortunately there was a lot of playing defense,” says Heaphy, the U.S. attorney from Western Virginia. “There were crises of the moment that had to be responded to and there just wasn’t enough bandwidth or space to do everything.”

Still, Holder sent some early signals that he intended to challenge the rigid sentencing policies. Among them was reversing the “Ashcroft memo,” an edict from former Attorney General John Ashcroft compelling federal prosecutors in all instances to pursue and charge the most serious offenses they could sustain under the law. Holder was deeply skeptical of the one-size-fits-all approach to prosecutions and took the handcuffs off his U.S. attorneys, allowing them to pursue charging decisions more narrowly tailored to individual circumstances. In some cases, that allowed the Justice Department to circumvent mandatory minimums.

“Eric’s memo is evidence of his pragmatic, smart-on-crime approach,” says James Garland, a friend and former top adviser. “By requiring prosecutors to make an individualized assessment when making charging decisions, Eric sought not only to promote fairness, but also to ensure more effective law enforcement.”

In 2010, momentum was gathering in Congress to repeal the crack vs. powder cocaine sentencing disparities. The administration put its muscle behind the legislation and Holder worked successfully behind the scenes to bring along law-and-order Republicans like Jeff Sessions of Alabama.

But it wasn’t until last summer that a more comprehensive reform effort started to stir in Holder’s mind. Vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard, Holder pulled out his iPad, called up the Notes App, and began noodling a memo to Obama on his second-term priorities. The election was still three months off, but Holder wanted to be ready. Among the first things he typed: “reviewing the war on drugs” and “criminal justice system review.”

In the memo he eventually sent to Obama last December, Holder argued that, liberated from the needs of a reelection campaign, they could now swing for the fences and push for comprehensive reform. Obama agreed and Holder established multiple working groups to develop the proposals. Last month Holder previewed his speech to Obama in an Oval Room session. Obama seemed especially engaged in the issues, according to a source familiar with the meeting. Then, almost exactly a year to the day from when Holder tapped out those first inklings on his iPad, Holder interrupted his annual Martha’s Vineyard retreat and flew to San Francisco to deliver his speech.

Next month, Holder will begin traveling around the country to spotlight innovative state and federal programs that are reducing prison overcrowding, easing recidivism rates, and restoring a measure of fairness to a creaky and beleaguered justice system. Mingling with judges, prosecutors, and criminal-justice professionals, he’ll be in his element.